A Case of Ocular Toxocariasis Successfully Treated with Albendazole and Triamcinolon

Article information

Abstract

We present a case of ocular toxocariasis treated successfully with oral albendazole in combination with steroids. A 26-year-old male visited the authors' clinic with the chief complaint of flying flies in his right eye. The fundus photograph showed a whitish epiretinal scar, and the fluorescein angiography revealed a hypofluorescein lesion of the scar and late leakage at the margin. An elevated retinal surface and posterior acoustic shadowing of the scar were observed in the optical coherence tomography, and Toxocara IgG was positive. The patient was diagnosed with toxocariasis, and the condition was treated with albendazole (400 mg twice a day) for a month and oral triamcinolone (16 mg for 2 weeks, once a day, and then 8 mg for 1 week, once a day) from day 13 of the albendazole treatment. The lesions decreased after the treatment. Based on this study, oral albendazole combined with steroids can be a simple and effective regimen for treating ocular toxocariasis.

INTRODUCTION

Toxocariasis is a disease caused by opportunistic infection with the dog roundworm (Toxocara spp.). It is uncommon in adults, but is a major cause of blindness in children [1,2,3,4]. In South Korea, many toxocariasis cases in adults are distinctively caused by eating raw meat or raw intestines of animals [5,6]. Eggs from the worms hatch into larvae in the small intestine that penetrates the walls of the digestive tract and may migrate to various organs (e.g., the lungs, skin, brain, and eyes) via the vascular system [2]. So, there are 3 major clinical syndromes of toxocariasis, i.e., visceral larva migrans syndrome (VLM), ocular larva migrans syndrome (OLM), and covert toxocariasis (CT) [4]. OLM appears mainly in healthy people and can be classified into 3 clinical types (peripheral inflammatory mass, posterior pole granuloma, and diffuse nematode endophthalmitis) by Wilkinson and Welch [7,8,9]. When it becomes severe, retinal detachment caused by retinal granuloma or vitreoretinal traction syndrome may cause blindness without leukocytosis, increased IgE level, or eosinophila [4]. Historical diagnosis is not confirmative, even inferable, whereas laboratory diagnosis is supportive. ELISA is one of the standard diagnostic measures [10,11,12].

There have been controversies regarding the treatment of OLM [13,14]. Systemic anthelmintics are often used to treat severe toxocariasis [13,14]. However, anthelmintics are not recommended because they may cause severe immune responses against dead larvae and their by-products, and severe visual acuity loss [4,13,14].

This report presents a case of toxocariasis with OLM treated with systemic albendazole (Albendazole Tablet, DaeWoong Pharm. Co., Seoul, Korea) and triamcinolone (Ledercort Tablet, SK Chemical Co., Seoul, Korea). Similar cases have been reported overseas, but none in South Korea [4,10,15]. The authors report here a case of toxocariasis with OLM that was effectively treated via non-surgical treatment with oral albendazole and triamcinolone, together with a brief literature review.

CASE DESCRIPTION

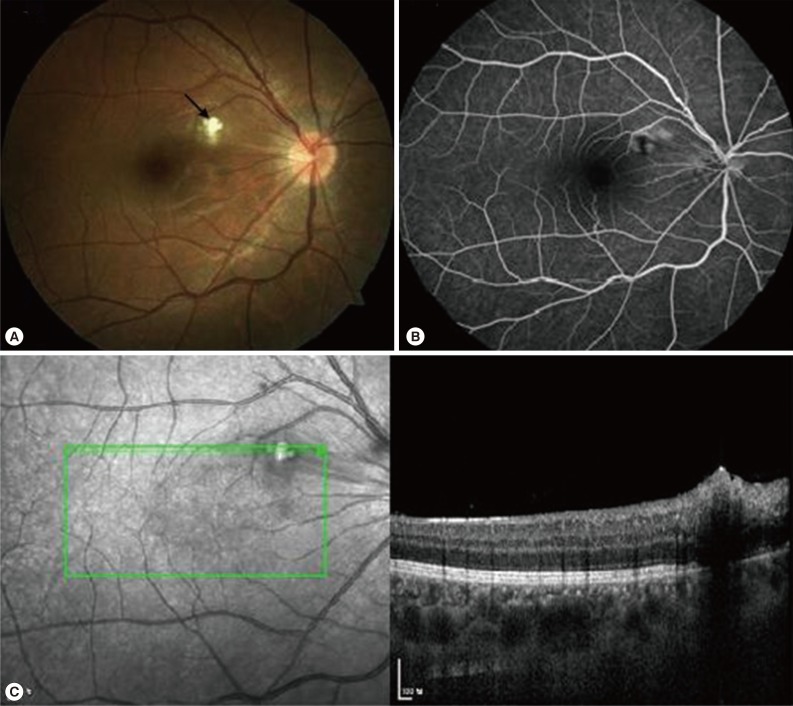

A 26-year-old male visited the authors' clinic with the chief complaint of flying flies in his right eye that appeared the night before. He had undergone laser-assisted subepithelial keratectomy for both eyes in September 2013 and had no ophthalmological or general medical history. His corrected vision was 1.0 for both eyes at the initial visit, and a fundus photograph showed a whitish epiretinal scar at the superonasal macular at the posterior pole in his right eye (Fig. 1A). The fluorescein angiography revealed the findings of retinochoroiditis characterized by a hypofluorescein lesion of the scar in its early stage and hypofluorescein lesions at the center of the scar with leakage at the margin in their later stage (Fig. 1B). An elevated retinal surface and posterior acoustic shadowing of the scar were observed in the optical coherence tomography (Fig. 1C). ELISA showed positive IgG reactions, and the patient was diagnosed with toxocariasis with OLM.

Fundus photograph, fluorescein angiography, and optical coherence tomography of the right eye at initial visit. (A) Fundus photograph shows whitish epiretinal scar (arrow) at the superonasal macular. (B) Fluorescein angiography reveals hypofluorescein lesion of the scar and late leakage at the margin. (C) Elevated retinal surface and posterior acoustic shadowing of the scar in optical coherence tomography before the therapy.

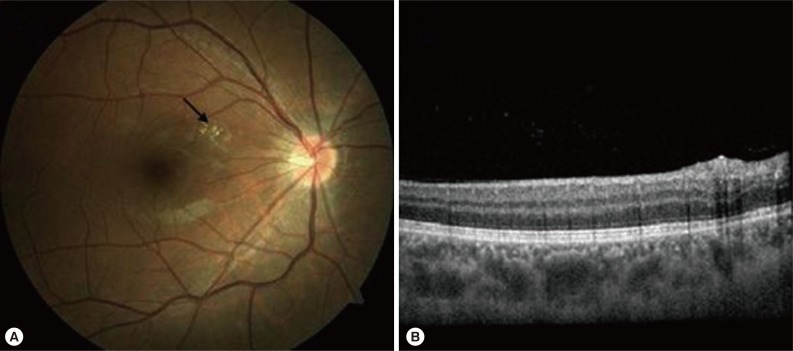

He was treated with albendazole (400 mg twice a day) for a month, and also with triamcinolone (16 mg for 2 weeks, once a day, and then 8 mg for 1 week, once a day) from day 13 of his albendazole treatment. The corrected visual acuity remained the same, and the scar slowly disappeared a month after the treatment (Fig. 2A). The optical coherence tomography results showed decreased elevation of the retinal surface and posterior acoustic shadowing of the scar (Fig. 2B). As the symptom was relieved, the patient did not show up. Thus, further ophthalmologic evaluation with immunological confirmation was not possible. The patient had the history of eating raw viscera of animals.

Fundus photograph and optical coherence tomography of the right eye at 1 month after oral albendazole and triamcinolon therapy from day 13 of albendazole treatment. (A) Fundus photograph shows disappearance of the whitish epiretinal scar (arrow). (B) Decreased elevation of retinal surface and slightly remained posterior acoustic shadowing of the scar in optical coherence tomography.

DISCUSSION

The featured case presents the first successful and effective treatment of toxocariasis with OLM in South Korea with oral albendazole for a month and oral triamcinolone from day 13 of albendazole treatment and without surgery.

Toxocara canis can cause severe blindness in children or adults and occurs all around the world. As such, toxocariasis can be a major public health issue [3]. OLM is often found in children, usually in 1 eye, but rarely in both eyes. The clinical symptoms of OLM vary depending on the invasion into the eye at the point of the diagnosis, and are characterized by retinochoroid granuloma, retinochoroiditis, vitroretinal traction, papillitis, endophthalmitis, retinochroidal nematode, and keratoconjunctivitis [16,17]. The present case was the second clinical type of OLM, i.e., posterior pole granuloma type [7,8,9]. Physicians have to depend on the results of clinical and laboratory tests for diagnosis, as there may be no particular clinical symptoms of OLM. Moreover, they need to interrogate the patients about their contact with dogs, pica, or eating raw meat (muscles or intestines) of animals [5,6,15]. As the meat eating habit was present in our case, it is possible that the infection originated from consumption of raw viscera of animals [5,6].

Pathological evidence, i.e., larvae in the ocular tissue, is required to confirm the diagnosis of OLM. However, this method involves an invasive procedure and is not easy to find the larvae. As such, serology is used for the diagnosis. ELISA is a principal diagnostic test to detect Toxocara antibodies in sera, and western blot helps the immunological diagnosis of OLM [10,11,12]. VLM shows leukocytosis and eosinophilia in blood test results, and OLM shows normal results. The present case showed a positive result for Toxocara IgG in ELISA but no leukocytosis [2,11,12].

There have been controversies regarding the treatment of ocular toxocariasis that threatens the visual acuity of the patient. Surgeries are performed to treat the epiretinal membrane due to the infection, i.e., the rhegmatogenous or traction retinal detachment. Scleral buckling and vitrectomy are used for severe vitreoretinal reactions [1,17,18]. The proper timing of surgery is still controversial, but the management of the infection before surgery seems to reduce the possibility of forming an epiretinal membrane.

Severe toxocariasis is often treated using systemic anthelmintics combined with oral steroids. In our case, oral albendazole was used for a month, and oral triamcinolone was added for 3 months. This treatment regimen showed a good response. The exact mechanism of albendazole on Toxocara worms is still unknown, but the combined regimen of albendazole and steroids seems to be essential to prevent severe immune responses caused by dead larvae. As larvae cannot proliferate within human bodies, the immunosuppressive effects of steroids do not increase the risk of autoinfection [2,16].

Barisani-Asenbauer et al. [4] reported 5 cases of toxocariasis with OLM in patients aged 11-72 years to whom a high dose of albendazole (400-800 mg, twice a day) was given for 2 weeks and oral steroids (the dose was slowly tapered) were added for 3 months. Their report stated that the treatment was successful without recurrence during the mean 20.2-month observation period [4]. In conclusion, based on our experience and also on other reports, the combination therapy of oral albendazole and steroids is a simple and effective treatment for ocular toxocariasis.

Notes

We have no conflict of interest related to this work.