Heavy Hymenolepis nana Infection Possibly Through Organic Foods: Report of a Case

Article information

Abstract

We encountered a patient with heavy Hymenolepis nana infection. The patient was a 44-year-old Korean man who had suffered from chronic hepatitis (type B) for 15 years. A large number of H. nana adult worms were found during colonoscopy that was performed as a part of routine health screening. The parasites were scattered throughout the colon, as well as in the terminal ileum, although the patient was immunocompetent. Based on this study, colonoscopy may be helpful for diagnosis of asymptomatic H. nana infections.

INTRODUCTION

Hymenolepis nana, the dwarf tapeworm, is the smallest and a common tapeworm in humans worldwide. H. nana infection occurs more frequently in warm climates and temperate zones such as Asia [1], Central and South America [2,3], and Eastern Europe [4]. Light H. nana infections are usually asymptomatic, whereas heavy infections with more than 2,000 worms can induce a wide range of gastrointestinal symptoms and allergic responses. Chronic urticaria, skin eruption, and phlyctenular keratoconjunctivitis are frequently reported to be related to hymenolepiasis [5-7].

In Korea, the prevalence of H. nana infections has been reported to be low, ranging from 0.02% to 0.7%, from 1971-1997 [8-10]. The latest nationwide survey conducted in 2004 revealed a 0% infection rate [11]; however, there have been sporadic cases of H. nana infection [12]. We recently encountered a case of heavy infection with H. nana in a Korean man.

CASE DESCRIPTION

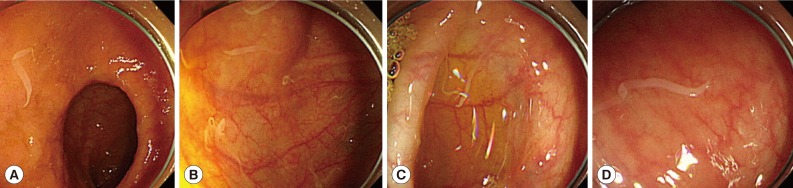

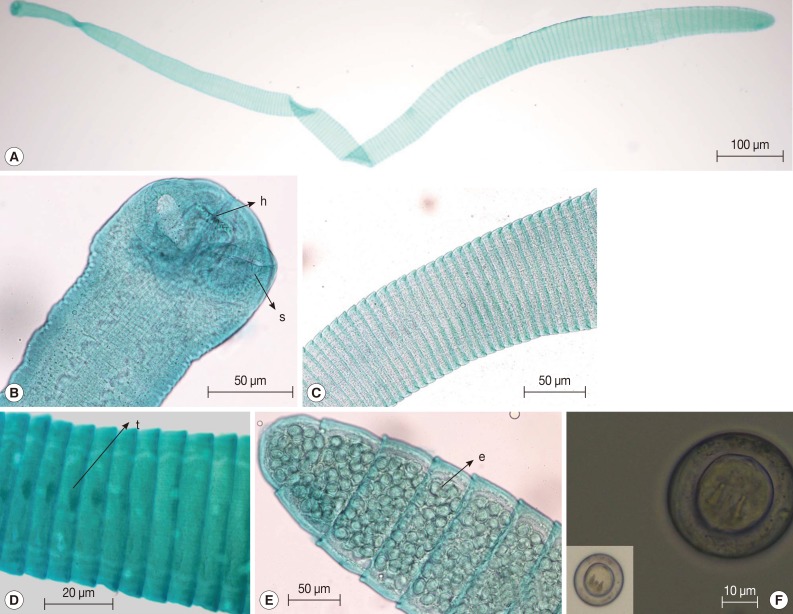

The patient visited a hospital in downtown Busan, Korea for a routine health screening. He was 44-years-old and stated that his diet included organic foods. He was previously diagnosed with chronic hepatitis (type B) and had taken medication for this condition for 15 years. There were no remarkable findings on physical examination and all laboratory tests were within normal limits. The colonoscopy, however, revealed that a large number of adult H. nana worms were scattered throughout the colon as well as in the terminal ileum (Fig. 1). Several worms were removed and fixed in alcohol-formalin-acetic acid (AFA) fixative. The specimens were stained with Semichon's acetocarmin and counterstained with fast green. The adult worm had a scolex equipped with 4 suckers, a hooked rostellum, and a strobila which comprised of up to 200 proglottids (Fig. 2A). The mature proglottids showed testes, while the terminal gravid proglottid was round and filled with eggs (Fig. 2D-F). Hence, the worms were identified as H. nana, and the patient was treated with praziquantel (Distocide™, Shinpoong Pharm. Co., Seoul, Korea), 20 mg/kg in a single oral dose.

Patient colonoscopy findings. Colonoscopy revealed that a large number of Hymenolepis nana adult worms were scattered throughout the colon as well as in the terminal ileum. (A) Terminal ileum. (B) Cecum. (C) Transverse colon. (D) Sigmoid colon.

Morphological characteristics of Hymenolepis nana adult worms. The adult worm was approximately 2 cm long and was comprised of up to 200 proglottids (A, C). The scolex was equipped with 4 suckers and a hooked rostellum (B). The mature proglottids showed testes, while the terminal gravid proglottid was round and filled with eggs (D, E). The eggs were round, with oncospheres that contained hooks (F). h, hooks; s, sucker; t, testis; e, eggs.

DISCUSSION

H. nana is one of a few parasites that can cause autoinfection which can persist for years. Autoinfection can lead to hyperinfection, especially in highly immunosuppressed hosts, which has been demonstrated in animal experiments [13]. However, the patient in this case did not have any indication of immunological problem. Hyperinfection also can be achieved by ingesting grain products contaminated by infected insects such as grain beetles. When humans ingest eggs, the oncospheres enclosed in the eggs are liberated and penetrate into the villi of the small intestine. After maturation is complete (~7 days), they return to the intestinal lumen by rupturing the villi. Tissue immunity is acquired in this process; however, cysticercoids liberated from the insects can penetrate the intestinal villi more easily because villi do not exhibit tissue immunity conferred by harboring cysticercoids. This low-level tissue immunity can lead to hyperinfection [12].

Kajiya et al. [14] reported a case of heart failure caused by hookworm infections. They assumed that the infection was associated with eating organic foods grown without pesticides [14]. The patient in our case also had a diet that primarily consisted of organic foods. We suspected that the organic foods the patient consumed could be a route of infection, because organic foods are not treated with insecticides and thus may harbor more insects.

Human H. nana infection was presumed to have been eradicated in Korea because it was not detected in recent nationwide surveys. However, Cho et al. [12] reported a case of H. nana infection in a Korean male. Proglottids of H. nana are rarely found in fecal samples because they do not ordinarily break off from the main strobili. In addition, national surveys usually use the Kato-Katz thick smear and saturated salt water flotation techniques to evaluate the prevalence of intestinal parasitic infections. The varying methods applied to surveys can lead to inconsistent results. Steinmann et al. [15] noted that the sensitivities of FLOTAC®, ether-concentration, and the Kato-Katz method were 95.6%, 58.8%, and 8.7% in H. nana egg detection, respectively. In addition, animals such as rats and mice can serve as reservoir hosts and can spread the disease to humans. Seo et al. [16] reported 1.2% (4/325) prevalence of H. nana infection in house rats (Rattus norvegicus) in Korea.

In conclusion, H. nana infection still occurs in humans in Korea although it is very rare. Animal hosts like rats and mice may act as a reservoir for human infections. Immunocompetent human hosts can develop a heavy H. nana infection brought about by its autoinfection characteristics. Documented cases of heavy infections and the report of Cho et al. [12] have demonstrated that regular health screening can be helpful in diagnosing asymptomatic parasite infections.

Notes

We have no conflict of interest related with this work.