Implications for selecting persistent hot spots of schistosomiasis from community- and school-based surveys in Blue Nile, North Kordofan, and Sennar States, Sudan

Article information

Abstract

In several schistosomiasis-endemic countries, the prevalence has remained high in some areas owing to reinfection despite repeated mass drug administration (MDA) interventions; these areas are referred to as persistent hot spots. Identifying hotspots is critical for interrupting transmission. This study aimed to determine an effective means of identifying persistent hot spots. First, we investigated the differences between Schistosoma haematobium and Schistosoma mansoni prevalence among school-aged children (SAC) estimated by a community-based survey, for which local key informants purposively selected communities, and a randomly sampled school-based survey. A total of 6,225 individuals residing in 60 villages in 8 districts of North Kordofan, Blue Nile, or Sennar States, Sudan participated in a community-based survey in March 2018. Additionally, the data of 3,959 students attending 71 schools in the same 8 districts were extracted from a nationwide school-based survey conducted in January 2017. The community-based survey identified 3 districts wherein the prevalence of S. haematobium or S. mansoni infection among SAC was significantly higher than that determined by the randomly sampled school survey (e.g., S. haematobium in the Sennar district: 10.8% vs. 1.1%, P<0.001). At the state level, the prevalence of schistosomiasis among SAC, as determined by the community-based survey, was consistently significantly higher than that determined by the school-based survey. Purposeful selection of villages or schools based on a history of MDA, latrine coverage, open defecation, and the prevalence of bloody urine improved the ability for identifying persistent hot spots.

In several schistosomiasis-endemic countries, the prevalence has remained high in some areas owing to reinfection despite repeated mass drug administration (MDA) interventions; these areas are referred to as persistent hot spots (PHSs) [1–3]. The World Health Organization (WHO) defines PHSs as communities with a schistosomiasis prevalence of ≥10% despite adequate treatment coverage (≥75%) of 2 rounds of preventive chemotherapy per year. The existence of PHSs makes it challenging to move toward the disease elimination phase [3]. Accordingly, identifying PHSs is significant for designing and implementing comprehensive interventions to control and eliminate schistosomiasis.

WHO set a goal for eliminating schistosomiasis as a public health problem (currently defined as a prevalence of heavy-intensity schistosomiasis infection of <1%) in 69 countries by 2025 and in all endemic (78) countries by 2030 [4]. The Federal Ministry of Health, Sudan (FMOH) is attempting to control schistosomiasis prevalence through MDA interventions and formulating an integrated strategy to transition from schistosomiasis control to elimination [5]. Therefore, the FMOH is exerting every effort for identifying PHSs while undertaking countrywide preventive chemotherapy on an annual basis in collaboration with the Schistosomiasis Control Initiative (SCI) and WHO.

From January to February 2017, a nationwide schistosomiasis survey was conducted in Sudan in 1,711 randomly selected primary schools to estimate the statewide prevalence of Schistosoma haematobium and Schistosoma mansoni in the 18 states [6,7]. Random selection was chosen to obtain precise estimates of schistosomiasis prevalence and the number of infected individuals. After the nationwide survey, since the FMOH had decided to use the randomly selected primary school dataset for MDA decision-making at the district level, several stakeholders at the state level approached the Korea International Cooperation Agency (KOICA) project team requesting an additional survey targeting villages they suspected had high prevalence. Their concern was that some “highly suspected” endemic districts might have been excluded from MDA interventions because the prevalence was estimated on the basis of the results obtained from randomly sampled schools. Consequently, in March 2018, the FMOH decided to conduct an additional survey targeting villages suspected to have high prevalence based on information from key informants (e.g., government officials, directors of state-level hospitals, and health workers with considerable experience in schistosomiasis mass treatment and related surveys). However, the results of a previous study cautioned that local health workers do not frequently possess precise information on the geographical distribution of schistosomiasis as it was noted that schistosomiasis prevalence among school-aged children (SAC) from purposively selected schools was not different from that of SAC at randomly selected schools [8]. To maximize the probability of identifying PHSs given the focal distribution of schistosomiasis, convenience sampling was deemed suitable for selecting schools or communities [9]. In several previous or existing schistosomiasis control programs, schools or communities suspected of high prevalence were randomly selected, and it cannot be determined how accurate the results were when considering the focal distribution of schistosomiasis. Random sampling has been widely adopted in surveys on MDA intervention; however, the extent to which randomly selected school- or community-based surveys are appropriate has not been thoroughly assessed. Recently, alternative sampling approaches have been introduced for identifying hot spots; however, empirical studies for comparing the prevalence of schistosomiasis among SAC between randomly and purposively selected cluster-based surveys are scarce [10,11]. For various actors in the fields of schistosomiasis control or elimination interventions, including MDA, it is critical to (i) understand whether ecological zone-level prevalence goes beyond a certain threshold and (ii) identify villages with higher prevalence. In this regard, discussions of adequate sampling methodologies based on empirical data have several policy and programmatic implications. Thus, we believe efforts are needed to determine to what extent these sampling methods influence the determined prevalence.

In this regard, we aimed to determine an effective means of identifying PHSs. We investigated whether a community-based survey in March 2018, selected by local informants and conducted 1 year following MDA, and a randomly sampled school-based survey conducted from January to March 2017, also conducted 1 year following MDA, in 8 districts of North Kordofan, Blue Nile, and Sennar States, Sudan produced different prevalences of schistosomiasis. In this study, the focus was placed on comparisons between “purposively” and “randomly” selected surveys at the cluster level rather than between “community” and “school”-based surveys.

This study used the data from 2 cross-sectional surveys conducted in the same 8 districts of the 3 abovementioned states. The community-based survey was conducted 13 months following the school-based survey; however, both surveys were conducted during the dry season 1 year following MDA.

Details of the first nationwide schistosomiasis and soil-transmitted helminthiasis survey conducted in 2017 have been previously described [6]. A total of 105,167 students from 1,711 schools in the 18 states of Sudan were recruited. Districts were divided into 3 ecological zones based on proximity to water bodies (near, <1 km; medium, 1–5 km; far, ≥5 km) as recommended by state government officials. Two-stage cluster sampling was used. The first stage involved classifying sample schools by ecological zones, and the second involved sampling students at schools. Five schools were selected from each ecological zone using the probability-proportional-to-size method, and a total of 60 students (30 male and 30 female SAC) were sampled from 2nd-, 4th-, and 6th-grade students. The WHO recommends 50 students per school; however, the FMOH sampled 60 to account for a possible 16% non-response rate [12]. For a community-based survey, 60 communities were purposively selected by local informants. After the communities had been identified, we selected 25 households in each community by systematic sampling. Data collectors randomly visited the first household identified near the center of a community and subsequently used intervals to identify the next visits in a clockwise manner.

The rationale used for determining the sample size of the community-based survey was that it be determined by treating communities as schools, as mentioned in the schistosomiasis control guidelines issued by WHO in 2006, which recommends 5 schools per district and 50 students per school. We included households with at least one male and one female SAC. Consequently, we selected 5–10 communities per district and 50 SAC per community. In addition to SAC, we recruited 2 adults per household (1 male and 1 female each).

Children aged<5 years, individuals with diarrhea or any severe illnesses, and those who had taken praziquantel during the previous 6 months were excluded. To compare the survey results, we used data from schools located in the same districts as communities selected by local informants.

An identical diagnosis method was used for both surveys, which was possible because most of the authors of this study were involved as supervisors in both surveys. Stool and urine samples were examined on the days of collection. The Kato–Katz and centrifugation methods were used to assess infection statuses and determine egg counts in stool and urine samples, respectively. For S. haematobium, eggs were double-counted within 1 h following centrifugation by 2 laboratory technicians. Infection intensities were estimated by counting the number of eggs per 10 ml of urine. The egg counts of S. mansoni were assessed by reading 2 stool smears using the Kato–Katz method.

We compared the district-wide prevalence of S. haematobium and S. mansoni among SAC as determined by the selected community-based survey and a randomly sampled school-based survey using Pearson’s chi-square test of proportions. We observed that egg counts were non-normally distributed; therefore, to determine the significance of egg count differences between the 2 samples, we used non-parametric analysis. To compare infection intensities determined by the 2 surveys, the Wilcoxon test (Mann–Whitney U test) was used. The analysis was performed using STATA 16 (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA), and P values of <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

The characteristics of participants in the 2 surveys are detailed in Table 1. A total of 6,225 individuals from 60 villages in 8 districts participated in the community-based survey, of whom 2,987 were children under the age of 15. Furthermore, we analyzed data obtained from 3,959 students at 71 primary schools that participated in the 2017 nationwide school survey residing in the same districts where the community-based survey was conducted. The average age of participants in the community survey was 24.3 (17.9) years, and the mean age of SAC in the community survey was similar to that of students in the school-based survey (10.1 (±2.7) and 10.9 (±2.2) years, respectively).

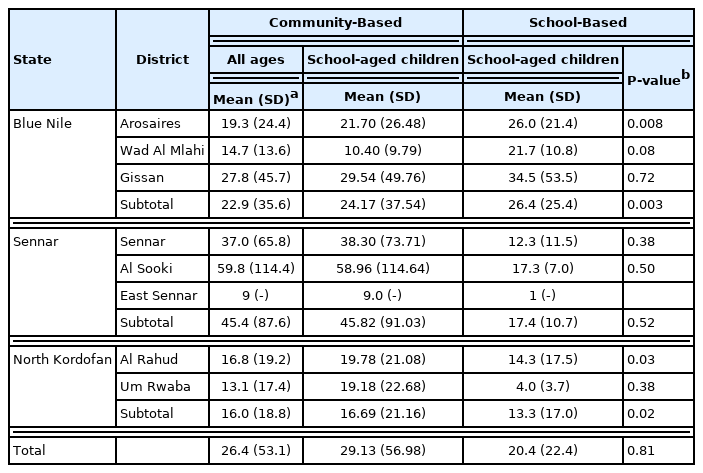

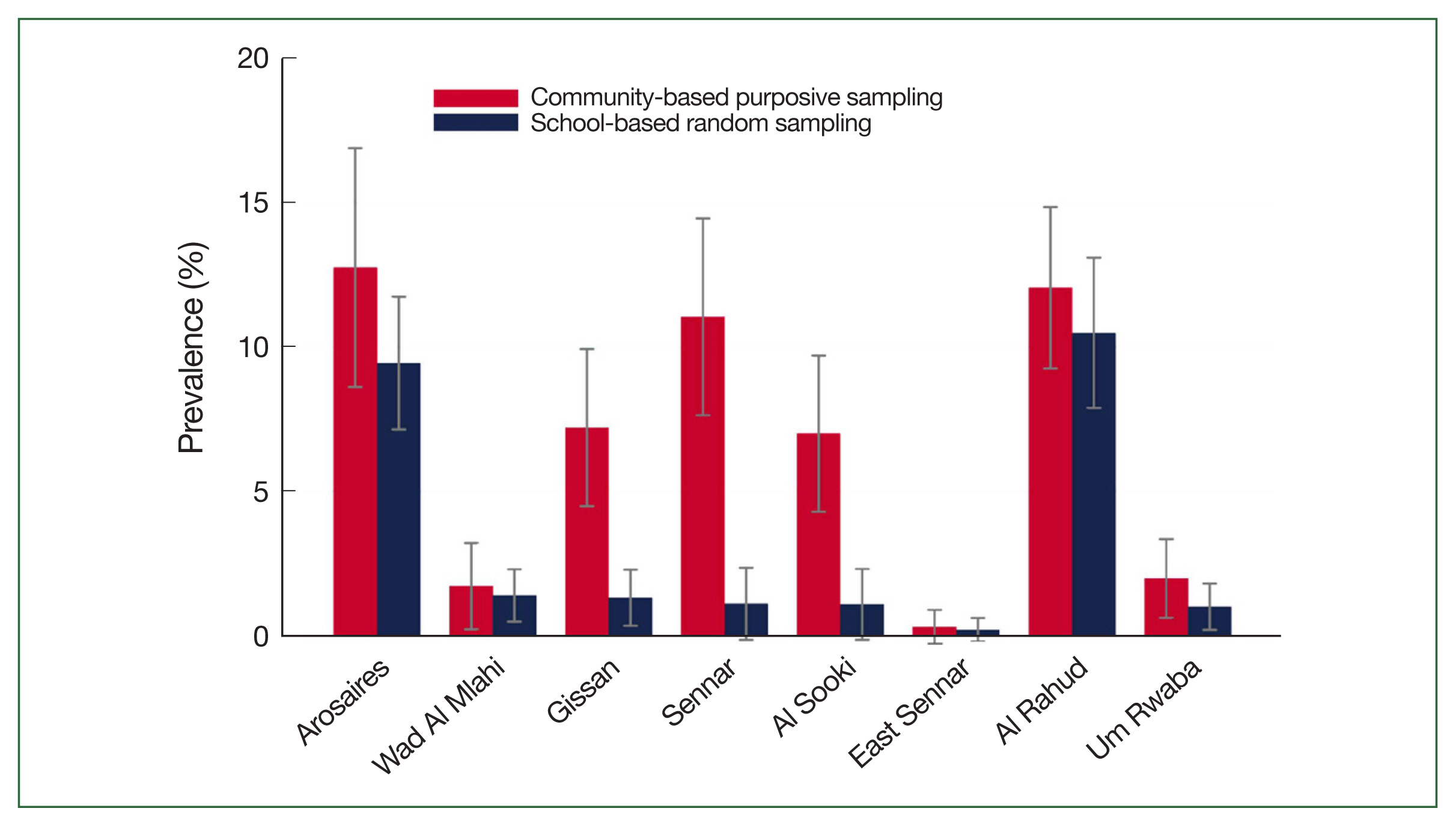

The community-based survey showed a higher statewide prevalence of S. haematobium among SAC than the school-based survey (Table 2; Fig. 1). As determined by the 2 surveys, differences between the prevalence of S. haematobium infections were substantial in localities, including Gissan in the Blue Nile state and Al Sooki and Sennar in the Sennar state. For example, according to the community-based survey, the prevalence of schistosomiasis among SAC in the Sennar district was 11%; however, this was only 1% according to the school-based survey. No significant difference between the 2 surveys was observed regarding the prevalence of S. mansoni or the infection intensities of S. haematobium or S. mansoni (Tables 3, 4).

Prevalence of Schistosoma haematobium infection by district and state as determined by the community-based and school-based surveys

Prevalence of Schistosoma haematobium among school-aged children (with 95% confidence interval) as determined by the 2 surveys (x-axis: district; y-axis: prevalence [%]).

Prevalence of Schistosoma mansoni infection by district and state as determined by community-based and school-based surveys

The community-based survey identified 3 districts wherein the prevalence of schistosomiasis (caused by S. haematobium or S. mansoni) among SAC was significantly higher than that determined by the randomly sampled school survey (e.g., S. haematobium in the Sennar district: 10.8% vs. 1.1%, P<0.001). At the state level, the prevalence of schistosomiasis among SAC, as determined by the community-based survey, was consistently significantly higher than that determined by the school-based survey.

This result is in contrast with that of a previous study, wherein it was reported that the prevalence of schistosomiasis among conveniently and randomly sampled SAC was similar [8]. In this study, the key selection criteria used for convenience sampling were a high prevalence, a history of repeated MDA interventions, and the presence of nearby water bodies. In other words, villages near potentially infested water bodies with a relatively high prevalence despite repeated MDA interventions were selected. We did not set any absolute values, including distance to water bodies, schistosomiasis prevalence, or the frequency, or number of MDA interventions, but rather relied on the opinions of local key informants, that is, mainly government officials of the State Ministries of Health and directors or health workers of hospitals and health centers, several of whom had more than 10 years of experience in their states. As was argued before the survey by these informants, some of the selected villages had a high prevalence, suggesting that local knowledge improves the ability for identifying PHSs and that collecting local knowledge from such sources when designing and implementing comprehensive interventions would be meaningful. However, we do not exclude the possibility that some villages not selected for the community survey may have had a higher prevalence.

The primary reason for employing random selection in a nationwide cross-sectional survey conducted in 2017 was to obtain precise estimates of state- and district-wide prevalence and determine the number of schistosomiasis-infected individuals. However, when the purpose of a survey is to target areas for MDA intervention, it is more significant to identify schools or villages with a high prevalence. In this regard, the present study demonstrates that convenience sampling is more appropriate for community selection when results are intended to identify areas for targeted MDA intervention, particularly when the overall district- or statewide prevalence is relatively low. In this context, identifying PHSs is critical because strategies should progress from control to transmission interruption, particularly in areas with a relatively low overall prevalence [13–16].

Similarly, when a schistosomiasis-related intervention cannot target all individual villages to improve latrine coverage, eliminate the practice of open defecation, control snails, and strengthen primary health care, it is critical that PHSs be identified because this enables integrated interventions to be performed more intensively and transmission to be more effectively addressed.

Before the community-based survey, we were uncertain of the extent to which the district-wide prevalence determined by the community and school-based surveys would disagree. The results obtained indicated that they managed to select villages with a high prevalence. In this study, the key informants for identifying hot spots were focal individuals in charge of neglected tropical diseases, who are government officials at the State Ministry of Health and Health Affairs (equivalent to District Health Offices in other countries), and community health volunteers. Subsequently, we observed that one of the key reasons why villages of high prevalence had been identified was that the key informants visited state hospitals and discussed the topic with health professionals. According to health professionals from state hospitals, primary healthcare facilities (e.g., primary healthcare and primary health units in Sudan) and rural hospitals at the district level do not have medical equipment for diagnosis or treatment. Therefore, symptomatic individuals must eventually visit state hospitals. Therefore, health professionals from state hospitals have limited information regarding villages from which patients resided.

The FMOH, in collaboration with WHO, SCI, and Korea International Cooperation Agency (KOICA), and in concert with the Schistosomiasis Elimination along the Nile river in Sudan with Empowered People (SENSE) project, has implemented a program (designed to run from 2020 to 2024) of integrated interventions to reduce the prevalence of schistosomiasis below 1% in the Khartoum, White Nile, Blue Nile, Gezira, North Kordofan, and Kassala states [17]. Identifying hotspots is critical for the interruption of transmission. After 10 years of continuous MDA interventions in the White Nile state, the prevalence of schistosomiasis has remained high in some villages and schools owing to persistent reinfection [18–20]. As part of the SENSE project, snail control, and sanitation improvements through community-led total sanitation complement the existing MDA program. Primary health care strengthening is another significant component of the SENSE project. To explore the extent of associations between schistosomiasis and probable risk factors, further studies are warranted.

Identifying PHSs is unlikely to be straightforward when data or reports on MDA histories or schistosomiasis prevalence are not well documented. This study indicates that key local informants are a significant source of information when selecting PHSs. If primary healthcare facilities have adequate equipment and de-wormers for diagnosis and treatment, then community dwellers would not have to travel considerable distances to state-level hospitals. If district health information systems functioned well, it would be easier to identify PHSs because information on patients and risk factors, including water, and sanitation coverage, would be available. The strengthening of primary healthcare systems has identified the need to combat schistosomiasis, particularly in areas of low prevalence, where merely conducting annual, or bi-annual mass Praziquantel treatments is inadequate. Furthermore, we recommend re-visiting the significance of primary health care from the perspective of the adequate selection of target villages, where schistosomiasis transmission is severe.

Ethical approval was obtained from the ethics review committee of the FMOH (FMOH/DGP/RD/TC/2016) and the ethical review board of the Korean Association for Health Promotion (130750–20,164-HR-020). For the community-based survey, written informed consent was obtained from household heads; for the school-based survey, written informed consent was obtained from head teachers and students. A separate informed consent form was developed for students, the script of this form was read to students by data collectors, and every detail was explained to the students. If a student decided to participate in the study, his, or her name was documented to record verbal consent. Owing to the large sample size, it was impractical to obtain written consent from the parents of school-aged children; instead, we obtained approval from the Institutional Review Board of the Federal Ministry of Health, Sudan. The survey protocol for informed consent complied with the standard procedure of the Federal Ministry of Health, Sudan.

Acknowledgements

This project was funded by the Korea International Cooperation Agency (KOICA, P-2015-00145). The funder had no role in the study design, data collection, and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

The authors thank the project team members for their efforts and contributions to controlling neglected tropical diseases in Sudan. They extend their appreciation to community members, the Ministries of Heath of 18 states, and the Federal Ministry of Health, Sudan. Special thanks go to Dr. Nahid Abdelgadir, International Health Directorate Project Management Unit, the Federal Ministry of Health, Sudan, and also to Mr. Dae Seong Cho, the field manager of the SUKO project.

Notes

Author contributions

Conceptualization: Ismail HAHA, Cha S, Jin Y

Data curation: Jin Y

Formal analysis: Ismail HAHA, Cha S, Jin Y

Investigation: Ismail HAHA

Methodology: Cha S

Software: Cha S,

Supervision: Jin Y, Hong ST

Validation: Jin Y, Hong ST

Visualization: Ismail HAHA, Cha S

Writing – original draft: Ismail HAHA, Cha S

Writing – review & editing: Jin Y, Hong ST

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.