Abstract

Hepatic alveolar echinococcosis (HAE), a life-threatening zoonosis, poses formidable surgical challenges when involving critical vasculature. Herein, we reported the periprocedural management dilemmas in radical resection for advanced HAE. A 58-year-old female visited the outpatient department presented with HAE. Imaging examination revealed extensive invasion of the hilum, bile duct, and several hepatic vessels, as well as left adrenal metastasis. The patient underwent right trisegmentectomy with left hepatic vein reconstruction, auto-transplantation, and adrenalectomy, with intraoperative Doppler demonstrating patent portal flow before abdominal closure. However, emergency thrombectomy and transcatheter thrombolysis were performed due to the abrupt occurrence of portal vein thrombosis 3 h after surgery. Despite intervention, the residual liver volume remained insufficient (approximately 28% of the standard liver volume), leading to progressive liver failure. The patient expired from multiorgan failure 9 days after operation. This case underscores not only the critical balance between radical resection and preservation of residual liver function in the surgical management of complex HAE, but also the imperative need to establish a comprehensive postoperative thromboprophylaxis.

-

Key words: Echinococcosis, liver transplantation, portal vein thrombosis

Introduction

Hepatic alveolar echinococcosis (HAE), caused by the larval stage of

echinococcus multilocularis, poses a significant zoonotic burden in endemic regions such as the Mediterranean, Central Asia, and East Africa [

1-

3]. Although the majority of hydatid cysts localize to the liver (50%–75%) or lungs (25%), invasive forms involving critical vasculobiliary structures remain formidably challenging in relevant therapies [

4,

5]. Notably, 2%–10% of hepatic cases exhibit intrahepatic vascular invasion, yet concurrent infiltration of portal veins, hepatic veins, and bile ducts—termed "complex echinococcosis"—constitutes a distinct clinical entity with a post-resection mortality exceeding 40% [

6].

The current consensus defines complex echinococcosis by the necessity for vascular/biliary reconstruction due to invasion of ≥2 major hepatic structures (Glissonian pedicles or hepatic venous confluences) [

7]. This advanced stage of disease correlates with catastrophic complications: 31% of patients develop vascular thrombosis, while 58% of patients progress to liver failure despite undergoing macroscopic radical resection [

8]. Pathophysiologically, parasitic-induced perivascular fibrosis disrupts endothelial integrity, creating a prothrombotic milieu exacerbated by surgical manipulation [

9].

This case report describes a 58-year-old female with complex HAE. Intraoperative findings revealed extensive invasion of the first and second hepatic hila, encasement of the right and middle hepatic veins, and involvement of the right hepatic duct, right portal vein branch, and right hepatic artery, accompanied by concurrent left adrenal metastasis. The patient underwent ex vivo right trisegmentectomy combined with left hepatic vein reconstruction, autologous liver transplantation, and adrenalectomy. Despite emergency thrombectomy and interventional thrombolysis for early postoperative portal vein trunk thrombosis, acute liver failure secondary to insufficient residual hepatic functional reserve ensued, culminating in fatal multiorgan failure on the postoperative day 9. Therefore, we present a fatal case of complex HAE with critical vascular invasion, managed through radical resection and auto-transplantation yet complicated by fulminant portal thrombosis, aiming to emphasize the critical importance of preoperative hemodynamic mapping and protocolized anticoagulation in mitigating catastrophic outcomes for such advanced cases.

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Chifeng Center for Disease Control and Prevention (approval No. 20250001). Informed consent was obtained from the legal guardian of patient whom consented to the publication of this case report.

Case Report

A 58-year-old female from a pastoral area in Chifeng, Inner Mongolia, presented with unexplained abdominal pain persisting for 1 month. She had a history of close contact with cattle, sheep, and foxes, without prior treatment-related history. Physical examination revealed no abdominal tenderness, and the liver and spleen were not palpable, but liver percussion pain was positive.

To investigate the potential source of exposure, metagenomic sequencing was performed on blood samples from livestock (dog, sheep, and rat) within the patient's household. The analysis revealed sequences aligning with

E. multilocularis, indicating environmental contamination and underscoring the risk of zoonotic transmission (

Table 1).

Laboratory examination showed alpha-fetoprotein at 2.37 ng/ml (normal <7.0), carcinoembryonic antigen at1.39 μg/L (normal <5.0) and negative echinococcus IgG antibody (ELISA) (optical density value 0.12, cut-off 0.35). It is noteworthy that up to 10% of diagnosed patients with confirmed alveolar echinococcosis may present with false-negative serological results, potentially due to immune exhaustion, sequestration of antigens within cysts, or technical limitations of the assay. Therefore, negative serology cannot unequivocally exclude the diagnosis, particularly in the context of highly suggestive imaging and histopathological findings.

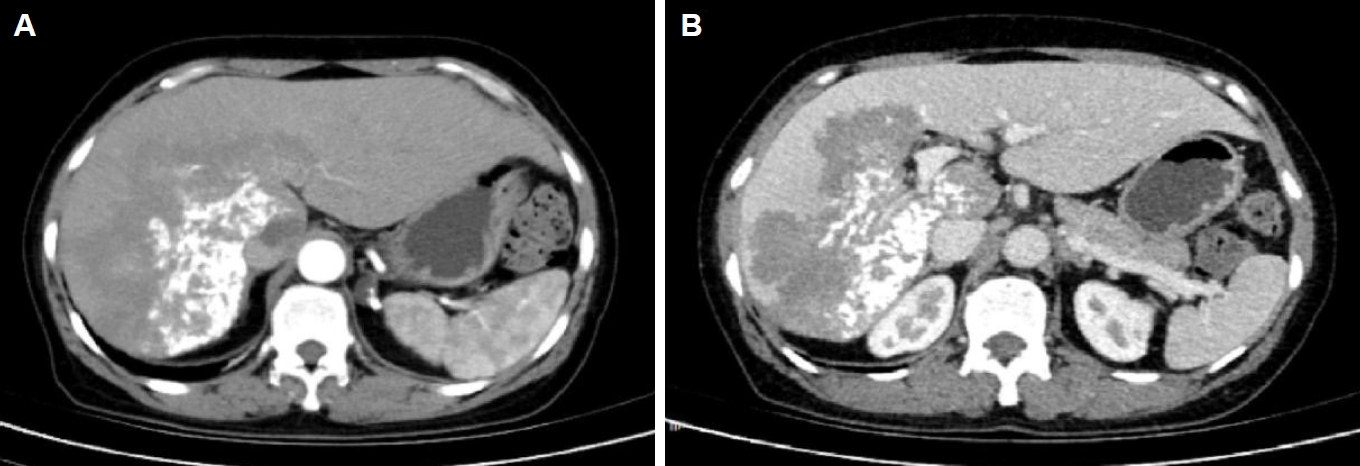

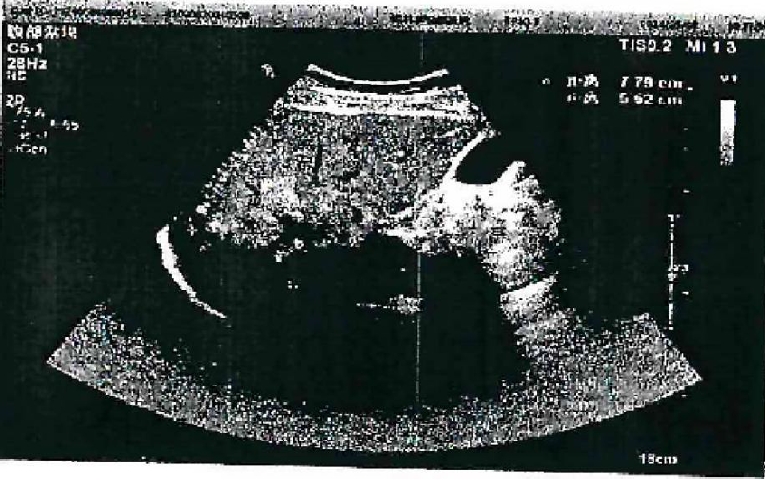

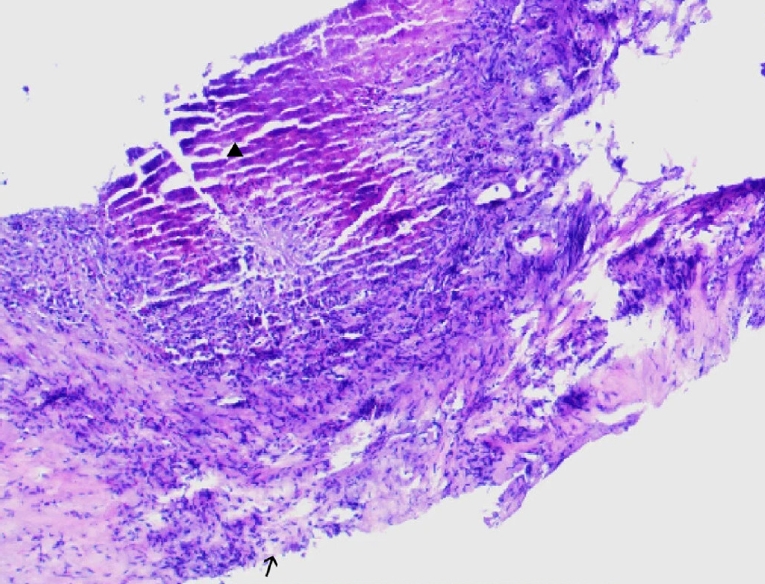

Ultrasound showed a heterogeneous hyperechoic mass (7.8×5.5 cm) with unclear borders in liver segments S4, S7, and S8 (

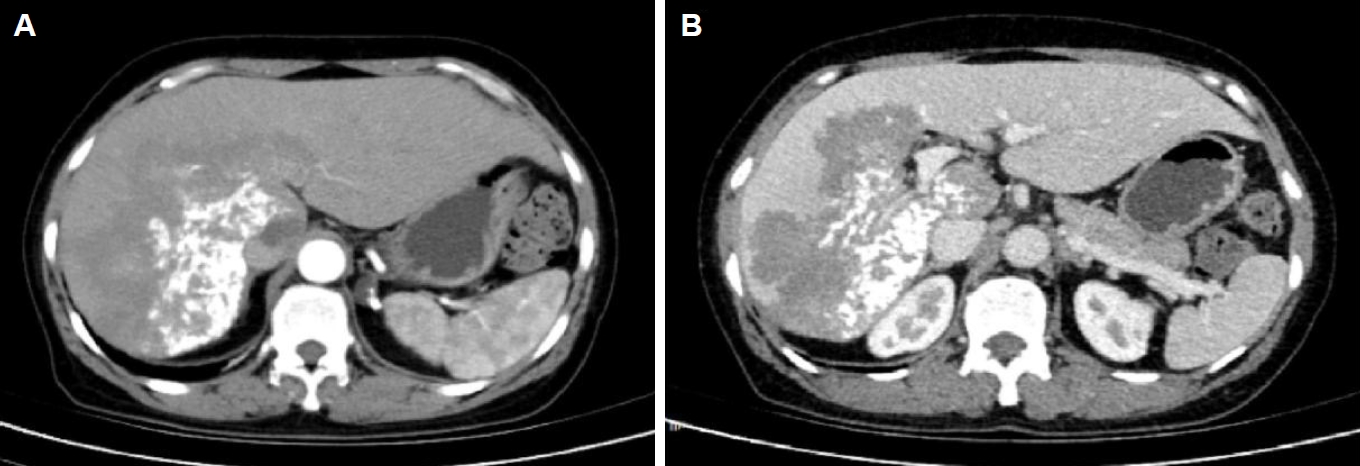

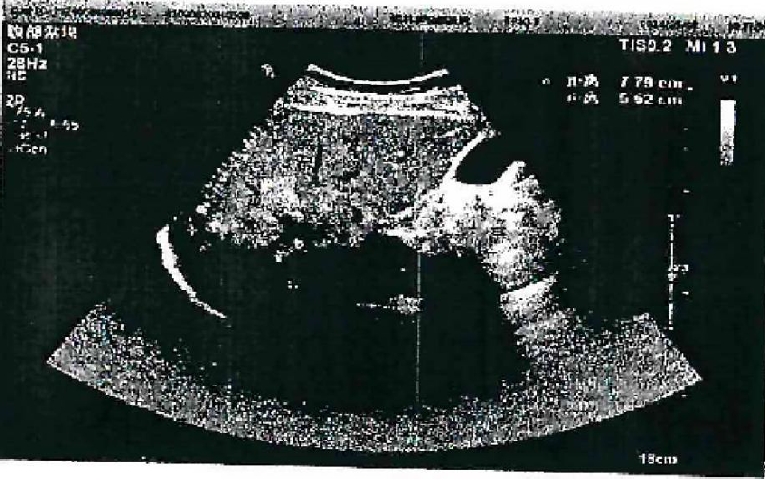

Fig. 1). Computed tomography suggested a large, poorly defined mass with mixed density and patchy calcifications (maximum cross-sectional area 15.11×11.29 cm) in the liver. No enhancement was observed in dynamic contrast imaging. A low-density lesion in the left adrenal gland showed no enhancement (

Fig. 2A). The right portal vein was narrowed. The right and middle hepatic veins were partially obscured in the portal venous phase (

Fig. 2B). The presence of a large, infiltrative mass with heterogeneous density and irregular calcifications is a recognized, though not universal, imaging presentation of advanced alveolar echinococcosis, which can mimic malignancy.

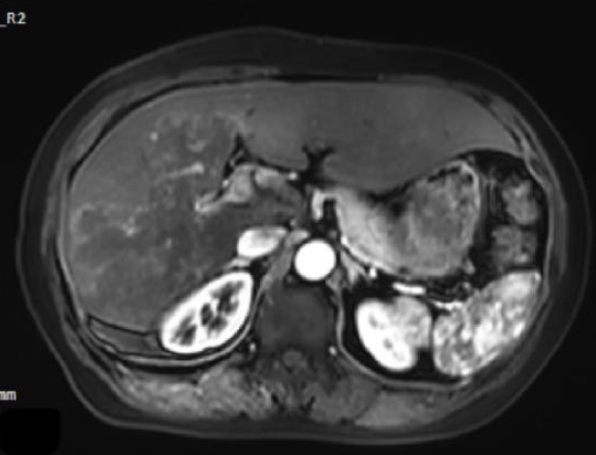

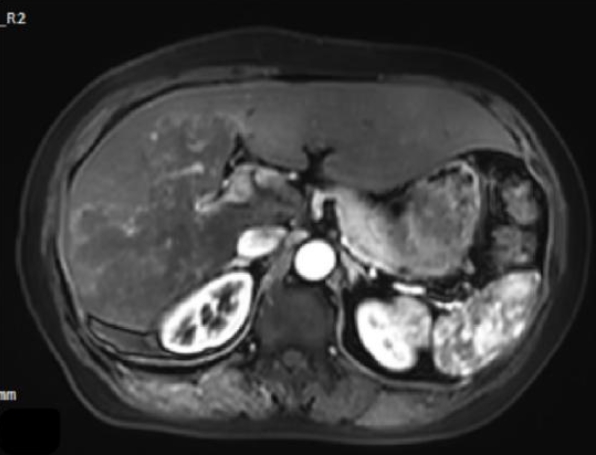

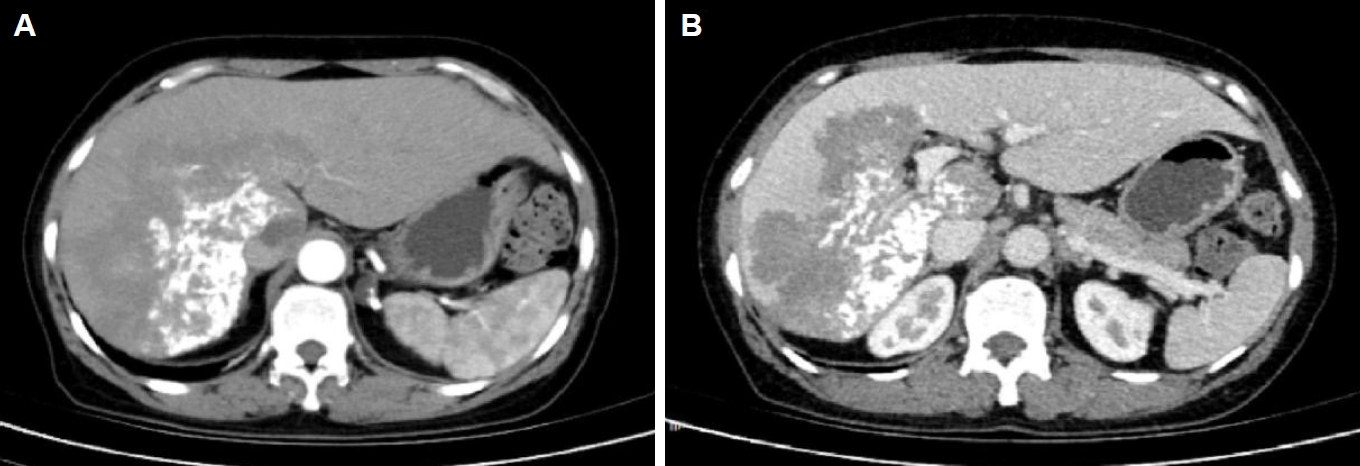

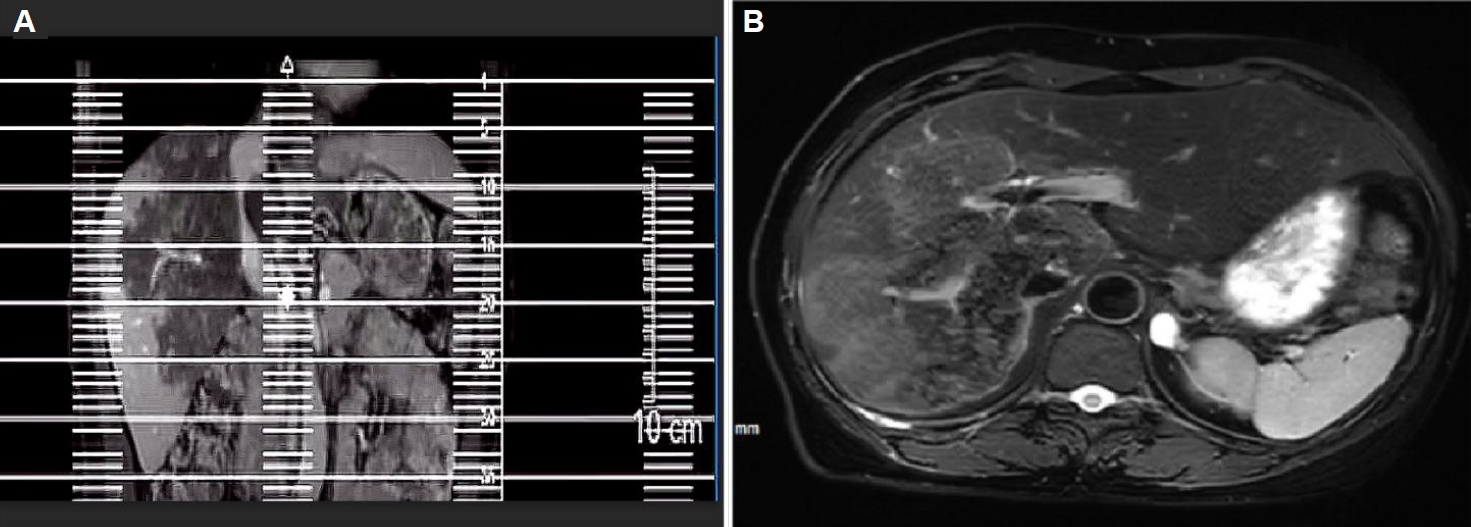

Magnetic resonance imaging showed irregular, slightly hyperintense T1 signals in the right lobe and caudate lobe (14.5×9.6×11.5 cm) without enhancement. The capsule showed enhancement, with inferior vena cava locally compressed. Diffusion-weighted imaging revealed slightly high signals (

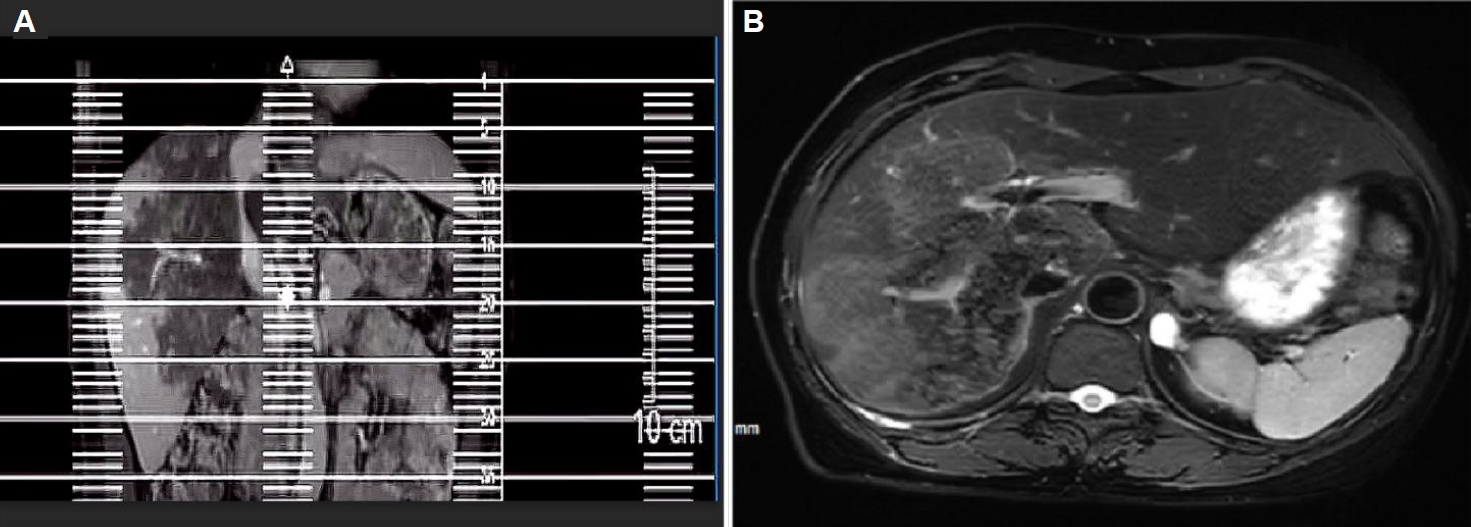

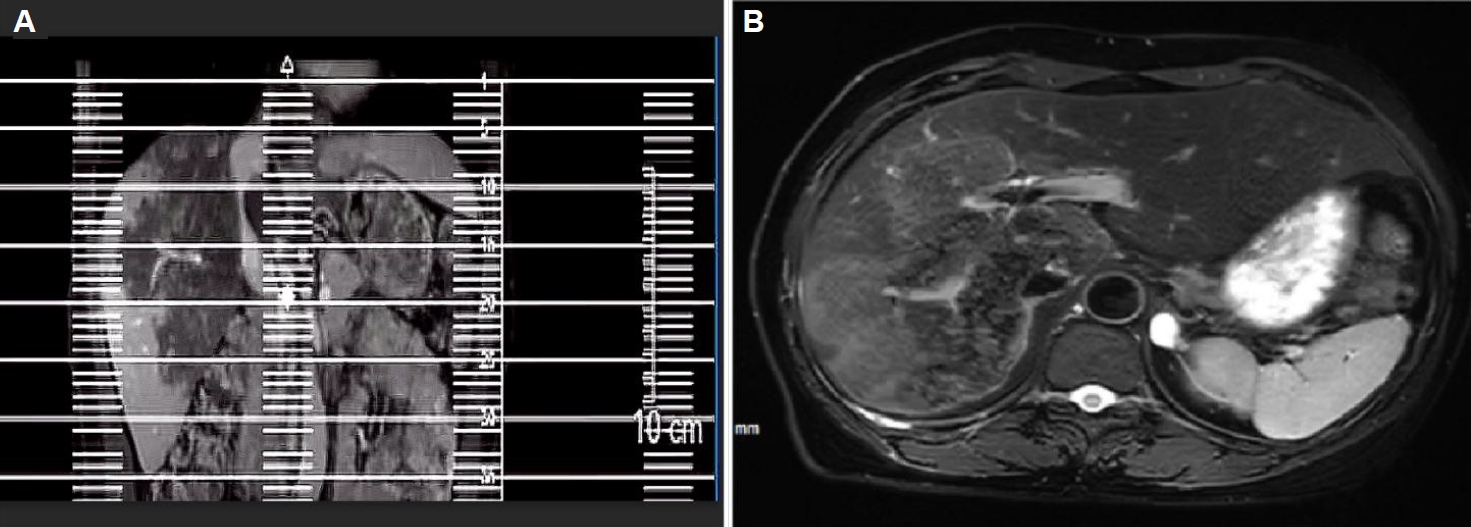

Fig. 3). T2-weighted imaging showed irregular, slightly hyperintense T2 signals in the right lobe and caudate lobe, with high diffusion-weighted imaging signals. A round, hyperintense T2 lesion (1.6×1.3 cm) was seen in the left adrenal gland (

Fig. 4A,

B). The absence of typical multilocular cystic structures cannot rule out HAE, as the disease may present as a solid, pseudotumoral mass with central necrosis and peripheral fibrosis, especially in endemic areas.

Child-Pugh score was classified as Class A (5 points), with the 15-min indocyanine green retention rate of 8.2% (normal <10.0%) and residual liver volume of 45.6% (520/1,140 g), meeting the criteria for autologous liver transplantation (>30.0%).

Intraoperative exploration revealed invasion of the left hepatic vein root. The patient underwent right trisegmentectomy with left hepatic vein reconstruction (using the portal vein), autologous liver transplantation, portocaval shunt, and left adrenalectomy. Intraoperative ultrasound confirmed patent blood flow in all vessels. The surgery lasted 12 h and 19 min, with 400 ml of blood loss and no transfusion. Postoperative hepatic vascular ultrasound suggested portal vein thrombosis (PVT), prompting re-exploration within 3 h. The liver appeared dark and swollen. Intraoperative ultrasound confirmed weak portal vein flow with thrombosis. Thrombectomy and portal vein reconstruction (using the umbilical vein) were therefore performed. Postoperative ultrasound and flowmetry confirmed normal portal vein flow.

PVT was detected 3 h postoperatively (flow velocity <5 cm/sec). Emergency thrombectomy revealed a mixed thrombus of 3.2 cm. By postoperative day 5, total bilirubin increased to 15.6 mg/dl (direct bilirubin >70%), and the international normalized ratio exceeded 3.0, meeting the criteria for acute-on-chronic liver failure (chronic liver failure consortium organ failure score: 11). On postoperative day 9, PVT recurred with left hepatic vein stenosis (narrowing >80%). Despite the operation of thrombolysis (recombinant tissue plasminogen activator 20 mg local infusion), the patient progressed to multiorgan dysfunction syndrome (sequential organ failure assessment score: 14) and died.

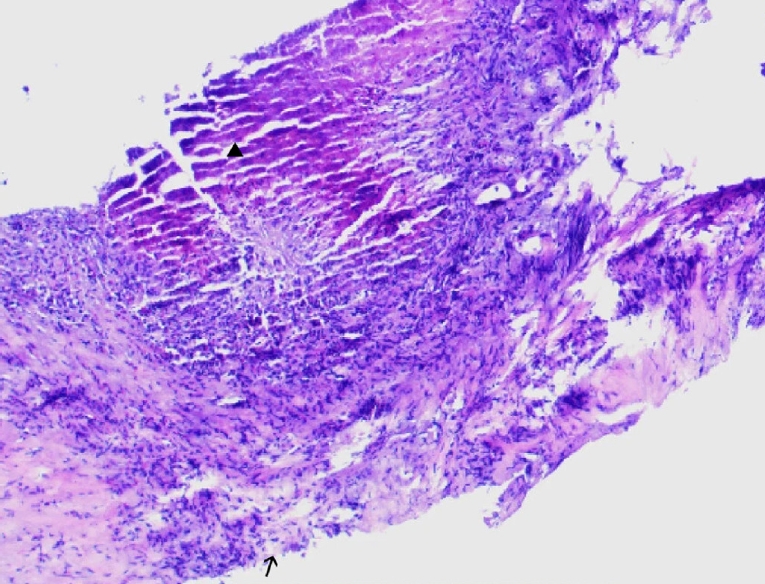

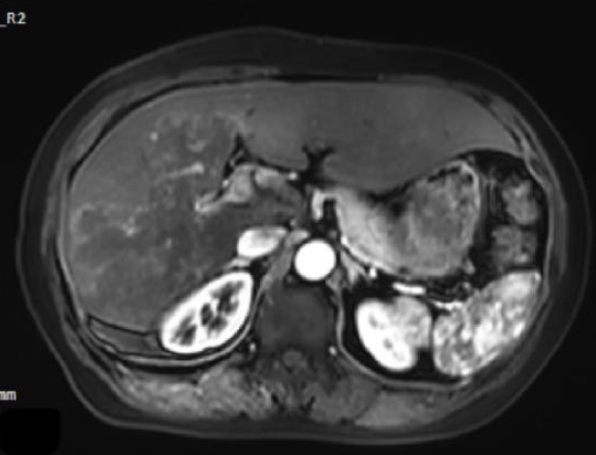

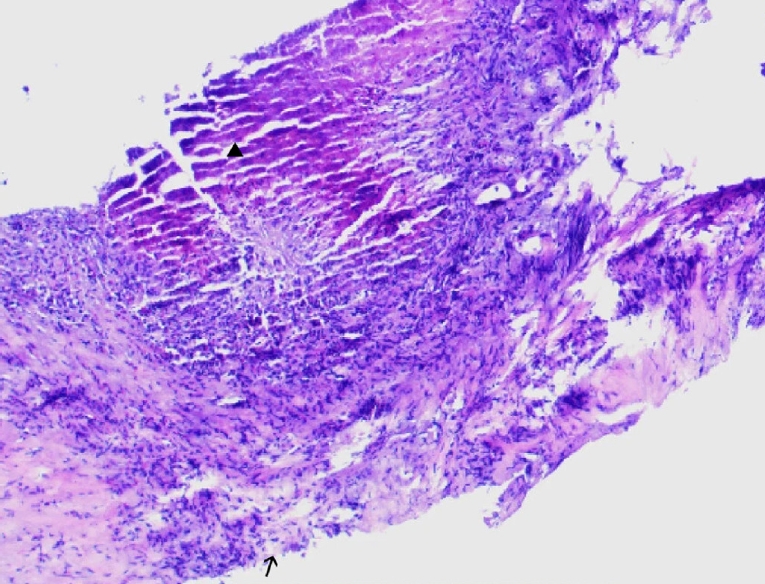

Postoperative pathology revealed features of alveolar echinococcosis, including extensive necrotic debris and peripheral palisading granulomatous inflammation with fibrosis (

Fig. 5). The presence of a characteristic laminated layer was observed. The overall histopathological architecture, in conjunction with the clinical and radiological presentation, was highly consistent with HAE despite the absence of protoscoleces.

Discussion

The definitive histological diagnosis of alveolar echinococcosis typically relies on the identification of parasitic structures, such as the laminated layer and protoscoleces within the lesion. In the present case, the pathological findings were highly suggestive of HAE, demonstrating the characteristic laminated layer and surrounding fibro-inflammatory response. However, the absence of observable protoscoleces on histopathology remains common, particularly in advanced cases where extensive necrosis and calcification may obscure parasitic elements, making it important to integrate pathological findings with serological, molecular, and imaging data for a conclusive diagnosis.

The imaging findings in this case, while not displaying the classic ‘hive-like’ multilocular cysts often associated with HAE, were consistent with an advanced and infiltrative pseudotumoral form of the disease. Key features such as the lack of enhancement, internal calcifications, and invasion of vascular structures have been well-documented in the literature on atypical HAE presentations. The radiological differential diagnosis primarily include infiltrative hepatocellular carcinoma or intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma; However, the diagnosis towards HAE is guided by the patient's epidemiological background, the stability of the lesion's characteristics across multiple imaging modalities, and ultimately the histopathological results.

HAE, caused by

E. multilocularis, is a zoonotic parasitic infection with a malignant clinical course. Inoperable or advanced HAE requires a long-term primary treatment of albendazole chemotherapy, which is typically lifelong. Radical resection is only feasible in a minority of patients with localized disease [

10-

12].

Due to the asymptomatic feature of the early-stage, many patients present at advanced stages of the disease. For advanced cases, liver reserve function and residual liver volume must be carefully assessed [

9]. Resection and reconstruction are necessary under the condition of involved major vessels, with autologous or synthetic grafts considered for extensive vascular defects [

10].

In this case, PVT developed within 3 h postoperatively. Although thrombectomy was performed, liver failure ensued, and PVT recurred on day 9, ultimately leading to death. PVT is a rare but severe complication of autologous liver transplantation. According to Yerdel's classification, this case was classified as Grade I, indicating surgical feasibility. However, despite early intervention, liver failure and recurrent thrombosis occurred, highlighting the high risk of PVT.

The development of postoperative PVT in this case stemmed from a multifactorial interplay of Virchow's triad components. Hemorheological abnormalities arose from hydatid cyst invasion at the left hepatic vein root, necessitating reconstruction after right trisegmentectomy. Postoperative angiography revealed a stenosis that can impair venous outflow and cause hepatic congestion, elevated portal pressure, and stasis, requiring balloon angioplasty. Vascular endothelial injury occurred due to cyst invasion into portal venous branches, mandating vascular reconstruction during autologous transplantation. This disrupted thromboresistance via increased platelet-activating factor (HMDB HMDB0009435)-mediated platelet aggregation, elevated endothelin-1 (encoded by gene EDN1, gene ID 1906, UniProt P05305), and reduced prostacyclin (synthesized by PTGIS, gene ID 5740, UniProt Q16647), thereby promoting vasospasm and thrombosis. Hypercoagulability emerged from a prolonged surgery lasting 12 h and 19 min, anesthesia-induced hemodynamic instability, anhepatic phase coagulopath caused by clotting factor consumption and delayed post-reperfusion synthesis. Concurrently, reduced fibrinolysis, hyperlactatemia, and hypocalcemia exacerbated coagulative dysregulation. Ischemia-reperfusion injury further destabilized the coordinated recovery of pro-/anticoagulant mechanisms, while left adrenalectomy extended operative trauma and fluid loss, indirectly amplifying the risks of PVT. Collectively, these factors precipitated a lethal cascade: PVT-triggered portal flow obstruction reduced hepatic perfusion by 60%–70%, inducing ischemic necrosis, failed regeneration, and fatal multiorgan failure although thrombectomy has been performed.

Postoperatively, there was an unstable equilibrium between the hemodynamic and coagulation systems of the patient, compounded by immature hepatic collateral circulation. Rapid PVT progression acutely obstructed portal flow, reduced hepatic perfusion by 60%–70%, and precipitated hepatocellular hypoxia, ischemic necrosis, and fulminant hepatic failure. Although thrombectomy was performed, ischemia-reperfusion injury and delayed hepatocyte apoptosis further compromised hepatic regeneration. Recurrent PVT precipitated irreversible liver failure, culminating in multiorgan dysfunction and mortality.

This case highlights the challenges in managing HAE with vascular invasion. Early diagnosis and multidisciplinary intervention are critical for prognosis. Postoperative complications such as PVT and hepatic failure remain formidable despite the therapeutic option provided by right trisegmentectomy combined with portal vein reconstruction. In endemic regions, heightened suspicion for parasitic infections and proactive screening are essential to mitigate disease progression.

Notes

-

Author contributions

Data curation: Huixia Y. Formal analysis: Huixia Y, Rongjian S. Investigation: Guojun L. Methodology: Guojun L. Resources: Rongjian S. Supervision: Jia Y. Validation: Runna Z. Visualization: Runna Z. Writing – original draft: Xin L, Mengmeng L. Writing – review & editing: Jia Y.

-

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

-

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our gratitude to Hongmei Bao for her invaluable technical assistance throughout this study. We also extend our thanks to Ping Huang for his helpful discussion and critical review of the manuscript.

Fig. 1.Abdominal color doppler ultrasound showed a heterogeneous.

Fig. 2.Abdominal computed tomography (CT) of the liver. (A) Arterial phase CT demonstrates a large hypodense occupying lesion in the liver with patchy hyperdense areas, showing no enhancement. A non-enhancing hypodense lesion is observed in the left adrenal region. (B) Portal venous phase CT reveals stenosis of the right portal vein branch within the lesion area, with partial obscuration of the right and middle hepatic veins.

Fig. 3.Magnetic resonance imaging demonstrates a large area of mildly prolonged T1 signal within the liver parenchyma, showing no enhancement post-contrast, with slightly hyperintense signal on diffusion-weighted imaging.

Fig. 4.(A) Magnetic resonance imaging T2-weighted imaging demonstrates mildly prolonged T2 signal in the right hepatic lobe and caudate lobe. (B) A round-shaped, hyperintense T2 signal lesion is observed in the left adrenal gland, which also shows high signal intensity on diffusion-weighted imaging.

Fig. 5.The histopathological examination reveals a characteristic laminated layer (▲), displaying a wavy eosinophilic structure. The germinal layer (→) shows hyperchromatic nuclei. Surrounding hepatic tissue exhibits inflammatory cell infiltration. H&E staining, ×400.

Table 1.Metagenomic-based screening for echinococcus multilocularis infection in domestic animals of alveolar echinococcosis patient's household

Table 1.

|

Sample ID |

Species |

Target |

Query sequence |

Matched species |

Accession |

Identity (%) |

E-value |

Matched gene/region |

|

D-01 |

Dog |

Serum antibody metagenomics |

0001_31224071500758_CFCDC01_F-COI |

E. multilocularis

|

Query_635351 |

90% |

5E-123 |

cox1 gene |

|

R-01 |

Sheep |

Serum antibody metagenomics |

0005_31224071500760_CFCDC45_F-COI |

E. multilocularis

|

Query_9585824 |

87% |

1E-122 |

cox1 gene |

|

P-01 |

Rat |

Serum antibody metagenomics |

0007_31224071500761_CFCDC61_F-COI |

E. multilocularis

|

Query_9233003 |

87% |

2E-122 |

cox1 gene |

References

- 1. Autier B, Gottstein B, Millon L, et al. Alveolar echinococcosis in immunocompromised hosts. Clin Microbiol Infect 2023;29:593-9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmi.2022.12.010

- 2. Bhutani N, Kajal P. Hepatic echinococcosis: a review. Ann Med Surg (Lond) 2018;36:99-105. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amsu.2018.10.032

- 3. Rostami A, Lundström-Stadelmann B, Frey CF, et al. Human alveolar echinococcosis: a neglected zoonotic disease requiring urgent attention. Int J Mol Sci 2025;26:2784. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms26062784

- 4. Hillenbrand A, Beck A, Kratzer W, et al. Impact of affected lymph nodes on long-term outcome after surgical therapy of alveolar echinococcosis. Langenbecks Arch Surg 2018;403:655-62. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00423-018-1687-9

- 5. Marquis B, Demonmerot F, Richou C, et al. Alveolar echinococcosis in solid organ transplant recipients: a case series from two national cohorts. Parasite 2023;30:9. https://doi.org/10.1051/parasite/2023008

- 6. Casulli A, Siles-Lucas M, Tamarozzi F. Echinococcus granulosus sensu lato. Trends Parasitol 2019;35:663-4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pt.2019.05.006

- 7. Zhaxi YD, Ping C, Zhuang ZN. Surgical management of complex hepatic echinococcosis. Chin J Curr Adv Gen Surg 2024;27:412-4. https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1009-9905.2024.05.019

- 8. Sączek A, Batko K, Krzanowska K, et al. Multicellular echinococcosis (alvococcosis) in a kidney transplant patient. Pol Arch Intern Med 2024;134:16705. https://doi.org/10.20452/pamw.16705

- 9. Woolsey ID, Miller AL. Echinococcus granulosus sensu lato and Echinococcus multilocularis: a review. Res Vet Sci 2021;135:517-22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rvsc.2020.11.010

- 10. Aji T, Dong JH, Shao YM, et al. Ex vivo liver resection and autotransplantation as alternative to allotransplantation for end-stage hepatic alveolar echinococcosis. J Hepatol 2018;69:1037-46. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhep.2018.07.006

- 11. Beldi G, Vuitton D, Lachenmayer A, et al. Is ex vivo liver resection and autotransplantation a valid alternative treatment for end-stage hepatic alveolar echinococcosis in Europe? J Hepatol 2019;70:1030-1. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhep.2018.12.011

- 12. Shen S, Kong J, Qiu Y, et al. Ex vivo liver resection and autotransplantation versus allotransplantation for end-stage hepatic alveolar echinococcosis. Int J Infect Dis 2019;79:87-93. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijid.2018.11.016