Abstract

The human gut is host to a diversity of microorganisms, including a parasite called Blastocystis. While there are increasing reports characterizing Blastocystis subtypes (STs) among healthy individuals, only a few studies have investigated the Blastocystis STs in renal or dialysis patients. This study investigates the Blastocystis prevalence and STs in hemodialysis patients. Fifty healthy controls and 100 chronic kidney disease patients undergoing dialysis participated in the study. Blastocystis infection was identified by using microscopic and molecular diagnosis using 18S rRNA-PCR. Then all positive samples were sent for sequencing to identify which ST they belong to. Phylogenetic and pairwise distance analyses were performed to confirm the validity of the STs. Thirty-four hemodialysis patients were infected with Blastocystis while 17 patients in the control were infected with the parasite. All positive samples were then confirmed using PCR. Genetic sequencing analysis subsequently revealed that 66% of Blastocystis infection belonged to ST1 and ST3 (33% each), followed by ST10 (20%), and ST6 (14%). The nucleotide sequence analysis of the 385 bp 18S rRNA gene revealed a >97% identity with previously identified Blastocystis isolates. The genetic analysis showed that the 8 identified isolates correspond to previously observed alleles. Six ST1 isolates produced a high frequency of Blastocystis isolates matching allele 4, with very low genetic divergence. ST3 isolates showed relatively increased genetic diversity and matching allele 34, which is the most common allele worldwide.

-

Key words: Blastocystis hominis, parasites, genotype, hemodialysis

Introduction

Blastocystis is a protozoan parasite that could infect both humans and animals. It was first reported in 1912 from human stool samples and diagnosed as a yeast but now it is classified as an intestinal parasite. Most of the infection is believed to be asymptomatic; however, some of the infected cases shown symptoms [

1]. It is believed that

Blastocystis may contribute to bowel disorders such as irritable bowel syndrome and inflammatory bowel disease [

2].

Significant genetic diversity has been observed among various

Blastocystis sp. strains isolated from different hosts [

3]. Thirty-eight subtypes (STs; ST1–ST38) have been obtained from humans and animals worldwide [

4,

5], while other STs have been found only in animals [

6]. It appears that STs 1, 2, 3 and 4 are the most common in human while the other 10 STs are frequently detected in other various animal groups such as birds and hoofed animals [

6,

7]. Different epidemiological aspects have been investigated by molecular studies such as transmission route, host specificity, and chemotherapeutic drug resistance.

Hemodialysis (HD) patients are highly vulnerable to severe infections since there are immunosuppressed. These patients are immunocompromised for various reasons, including the impairment of granulocyte and lymphocyte functions due to uremic toxins and malnutrition.

Due to weakened immunity, HD patients are more susceptible to various parasitic infections that can negatively affect their quality of life [

8]. Studies on the prevalence of parasitic infections among HD patients in Brazil, Turkey, Iran, and Saudi Arabia have revealed that

Blastocystis sp. is among the most frequently identified microorganisms, in addition to

Cryptosporidium,

Endolimax nana,

Entamoeba coli,

Entamoeba histolytica, and

Entamoeba dispar, and

Giardia lamblia [

9-

12]. Despite the significant burden of

Blastocystis sp. in humans, there is limited molecular research available that provides data on the prevalence and distribution of its STs in the Saudi population [

13,

14]. To date, no data are available on the prevalence and genotyping of

Blastocystis in Saudi HD patients. Therefore, in this study, we aimed to investigate the

Blastocystis prevalence and to identify the parasite STs in HD patients.

Methods

Ethics statement

The study was conducted after ethical approval (No.1439-280594) from the Medical Ethics Committee of the Saudi Ministry of Health, Makkah, Saudi Arabia, and informed consent form was signed by each participant.

Samples collections

The samples of the present study were collected from Saudi patients attending Al-Noor Specialist Hospital and King Faisal Hospital in Makkah, Saudi Arabia. Fifty healthy controls and 100 chronic kidney disease Saudi patients undergoing dialysis participated in the study. Each participant provided a stool sample in a clean dry container labelled with the patient’s name, then each sample was subjected to microscopic and molecular examinations.

Microscopic examination

The first step was the microscopic examination to detect the presence of

Blastocystis using direct smears, formol-ether concentration technique (Ritchie), and trichrome stating, as previously described [

15].

Different

Blastocystis hominis 18S ribosomal RNA gene sequences were extracted from GenBank (

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nucleotide/) and aligned using Clustal W to look for conserved regions for primer design. After the alignment was done, the best pair of primers were chosen and then checked using Primer blast to check the annealing temperature and the GC percentage (

Table 1).

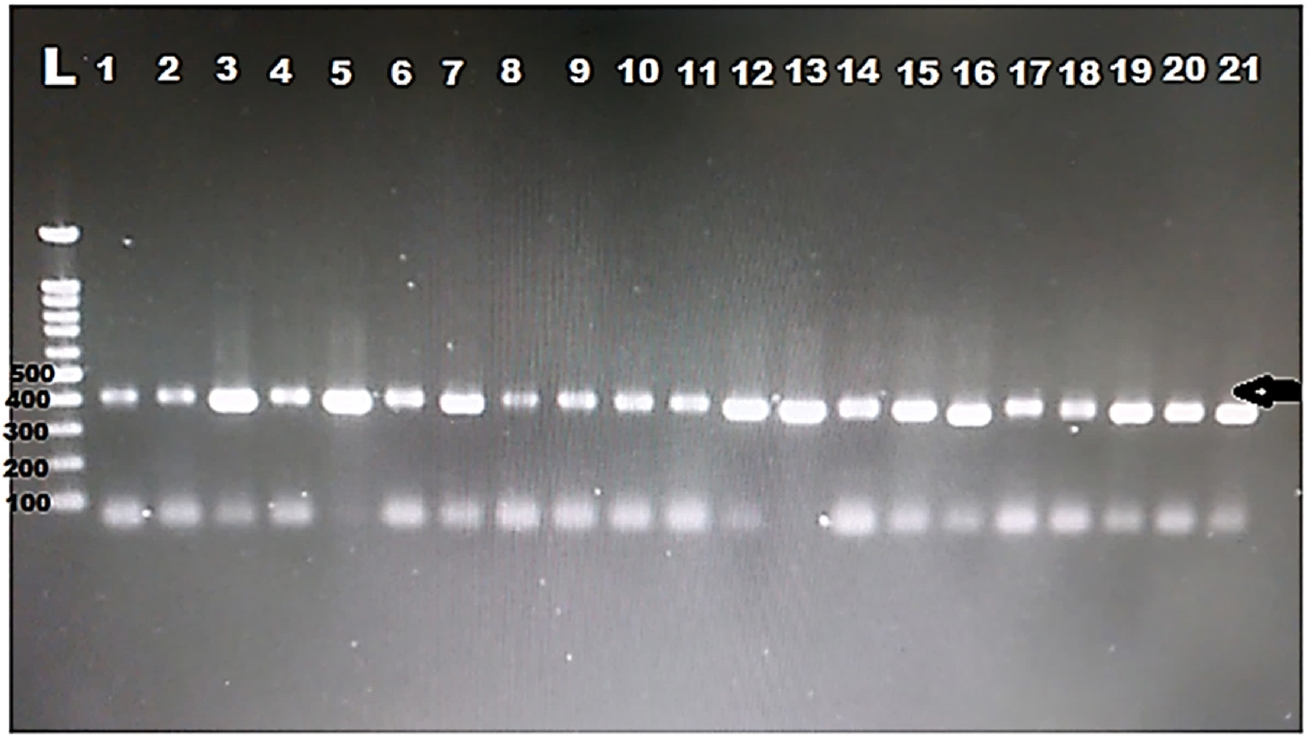

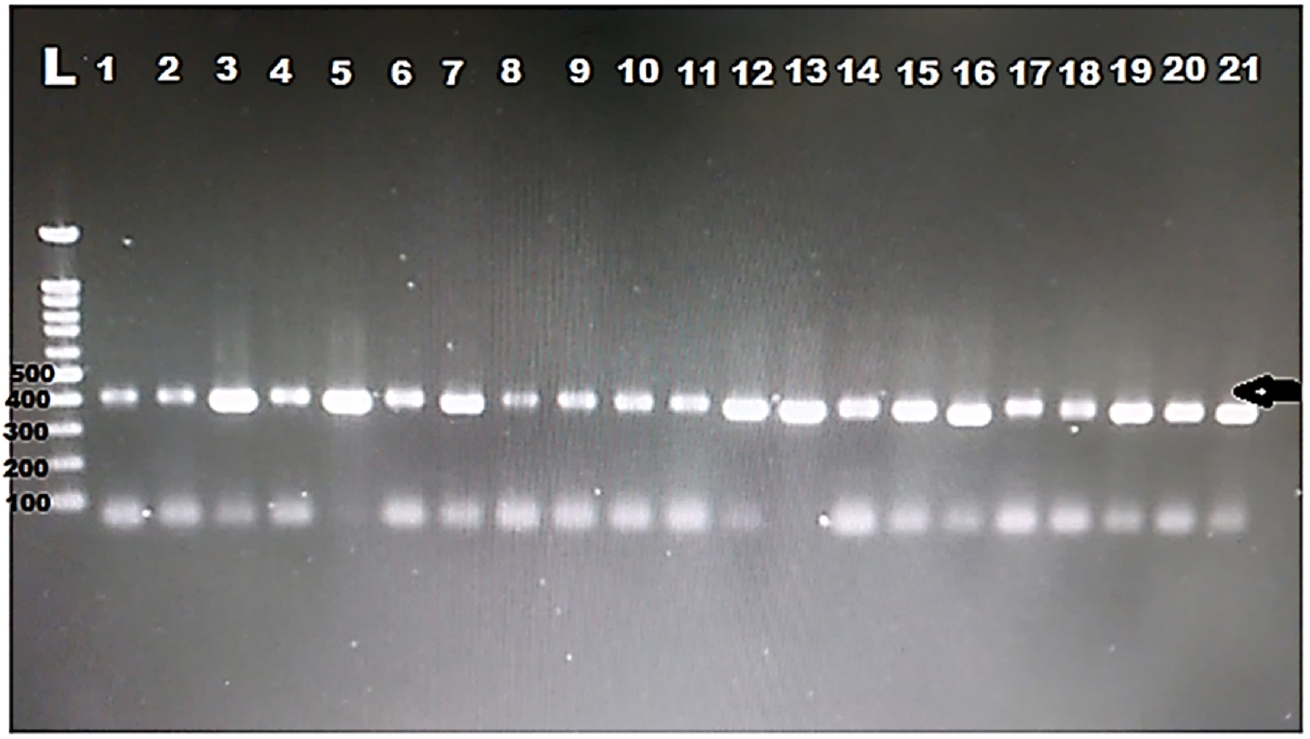

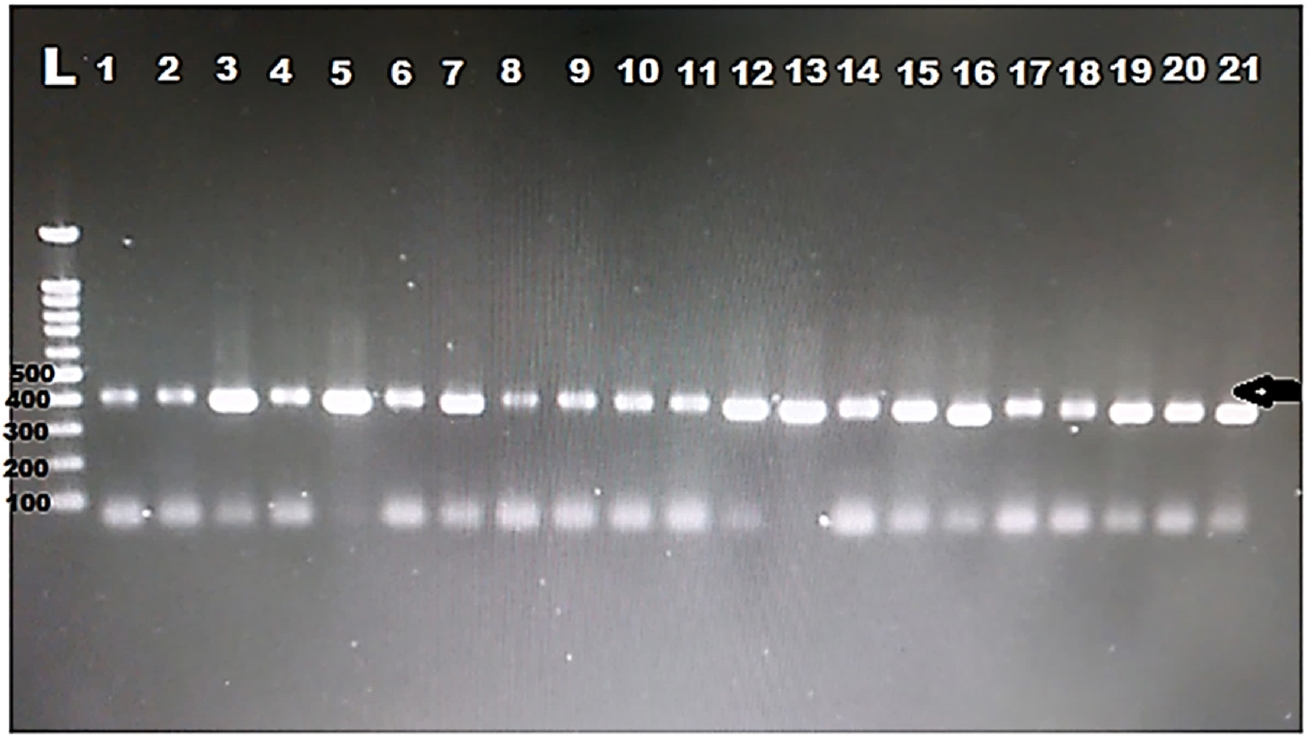

Samples tested for Blastocystis underwent DNA extraction, PCR, and sequencing. DNA was extracted from stool samples using the QIAamp Fast DNA Stool Mini Kit (Qiagen), following the manufacturer’s instructions. PCR was done using specific primers for Blastocystis amplifying 18S rRNA gene. The PCR conditions were as follows: The standard protocols followed for amplification that was: denaturation (95°C) for 5 min, 40 cycles for 40 sec at 95°C, annealing at a temperature 52°C for 40 sec, elongation at 72°C for 1 min with final elongation at 72°C for 10 min. Then electrophoresis on 1.5% agarose gels was used to isolate PCR products which were then visualized using UV. A 385-bp band was produced by positive Blastocystis sp. samples.

Sequencing and phylogenetic analysis

Eight positive 18S rRNA-PCR samples (385 bp) were selected and purified using the QIAquick PCR Purification Kit (Qiagen). These purified samples were then subjected to Sanger DNA sequencing with an automated DNA sequencer (ABI 3730XL DNA Analyzer). The sequences were analyzed using DNA BaserV3 software (Heracle BioSoft SRL).

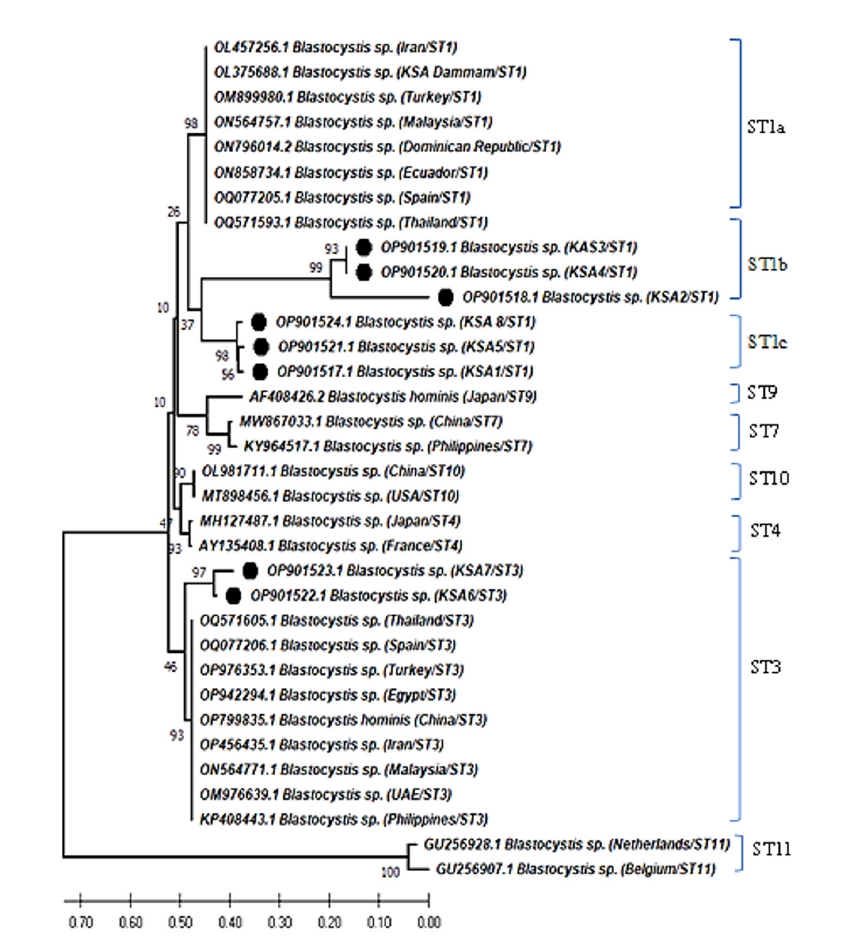

The alignment of small subunit ribosomal RNA sequences was conducted using the ClustalW in the MEGA version 12 (

https://megasoftware.net) and gaps and ambiguous sequences were removed by ocular inspection. Phylogenetic analyses using the neighbor-joining method and pairwise distances were performed. The phylogenetic tree for partial 18S rRNA sequences of

Blastocystis sp. was constructed using the neighbor-joining method in MEGA. The Kimura 2-parameter model was applied, and bootstrap analysis with 1,000 replicates was performed to assess the reliability of the tree.

The collected data were analysed using IBM SPSS version 25 (IBM Corp.). Chi-square test was used to analyse categorical variables and P-value of <0.05 was considered significant. Kappa coefficient was used to measure reliability for different techniques used in the present study.

Results

A total of 150 stool samples were collected from 100 HD patients (mean±SD, 51.57±10.5 years) and 50 healthy controls (mean±SD, 39.66±11.9 years). Most of the HD patients and control were male (55 out of 100 HD patients and 34 out of 50 control). Some HD patients and control cases had gastrointestinal manifestations as abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, and diarrhoea as shown in

Table 2.

All stool samples were examined for the presence of

Blastocystis by microscopy and conventional PCR. Microscopic examination showed that 34% (34/100) of the HD patients were infected with

B. hominis in comparison to 34% (17/50) of the healthy control who were infected with the parasite (

Table 3).

Among HD patients, using direct smear, Blastocystis was detected in 31 cases (31%), while Ritchie technique detected Blastocystis in 20 cases (20%). PCR diagnosed Blastocystis in 31 participants (31%). The total number of infected participants detected by all techniques was 34 (34%).

As shown in

Table 4, when direct smears proposed to be the gold standard method for detection, substantial agreement (0.764) was found with Ritchie technique, and perfect agreement (0.831) with real-time PCR. However, when Ritchie technique assumed to be the gold standard, substantial agreement was found with direct smears and real-time PCR. Then, when real-time PCR was nominated to be the gold standard, fair agreement was found with direct smears, and substantial agreement with Ritchie technique.

Among the 34 HD patients infected with

Blastocystis, males were at a higher percentage (21/55, 38.2%) compared to females (13/45, 29.9%).

Table 5 shows the distribution of clinical characteristics (abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, and diarrhoea) among HD patients.

Blastocystis infection was more commonly associated with abdominal pain (64.7%) than other gastrointestinal symptoms. There were no statistically significant differences between the 2 groups in any of the variables studied, including gender (

P=0.329), abdominal pain (

P=0.689), nausea (

P=0.666), vomiting (

P=0.948), and diarrhoea (

P=0.758).

DNA was extracted from all the positive samples, then PCR amplification of the 18S rRNA gene was successfully done for all samples (

Fig. 1). Then, all the PCR products were sent to Macrogen for sequencing. Eight different sequences were obtained. The obtained sequences were analysed using BLASTN software for comparison with the 18S rRNA sequences deposited in the GenBank. The nucleotide sequence analysis of the 385 bp 18S rRNA gene revealed a >97% identity with previously identified

Blastocystis isolates. Sequence analysis showed that the majority of

Blastocystis isolated in the present study belong to

Blastocystis sp. ST1 (33%) and ST3 (33%). ST10 was identified in 20% and ST6 in 14% of samples. The results of allele discrimination revealed the presence of alleles 4 in all ST1 samples. ST3 exhibited alleles 34, 38, and 59. ST6 represented alleles 122 only. The only ST10 was allele 152.

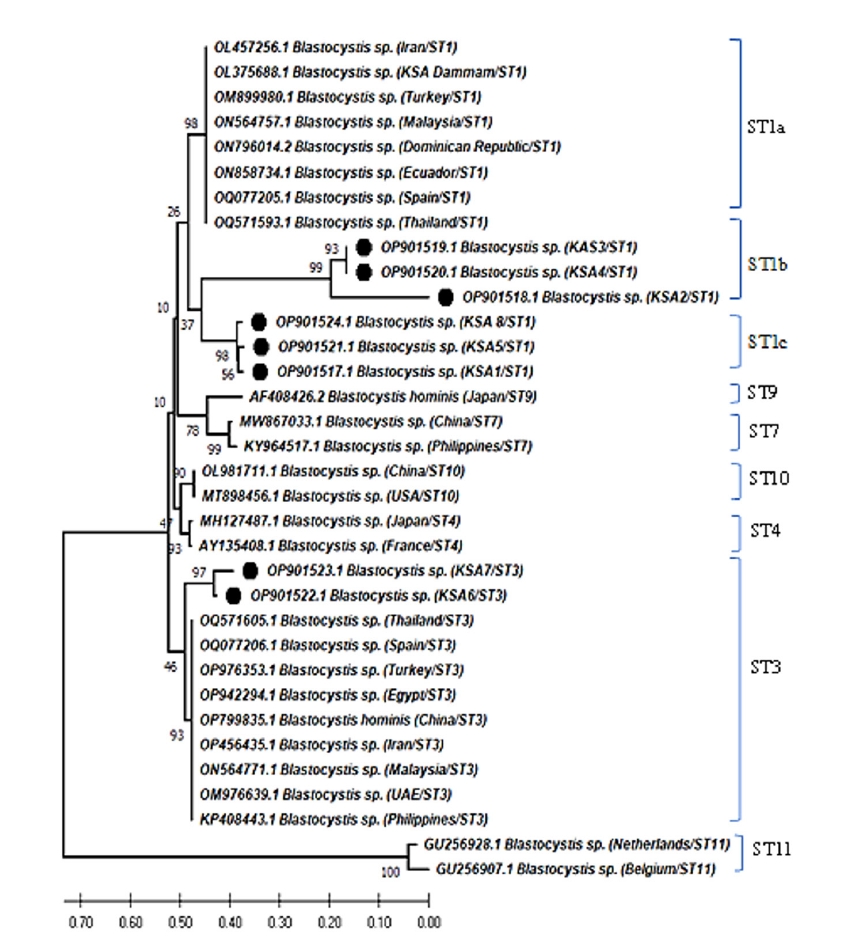

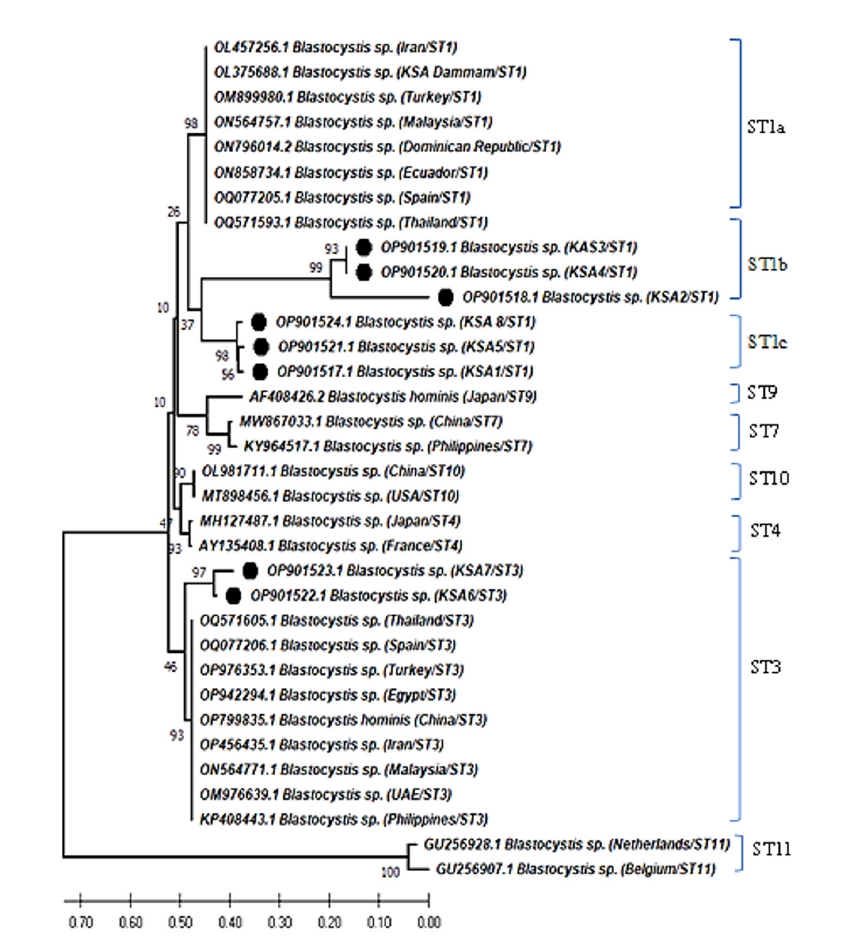

The phylogenetic analysis of

Blastocystis sp. revealed that 6 different sequences were on the same clade as

Blastocystis ST1 and 2 sequences were placed on the same clade as

Blastocystis ST3 (

Fig. 1). Two zoonotic STs, ST1 (6/8, 75%) and ST3 (2/8, 25%) were detected in this study. Among them, ST1 infection was the predominant and the related isolates were placed on 2 branches of the same clade as ST1b and ST1c with 37% nodal support (

Fig. 2). Further, the phylogenetic tree revealed that

Blastocystis isolates in the present study were most closely related to

Blastocystis isolates from Thailand and grouped with isolates from the Middle East, Asia, North Africia, Ecuador, Spain, and the Dominican Republic.

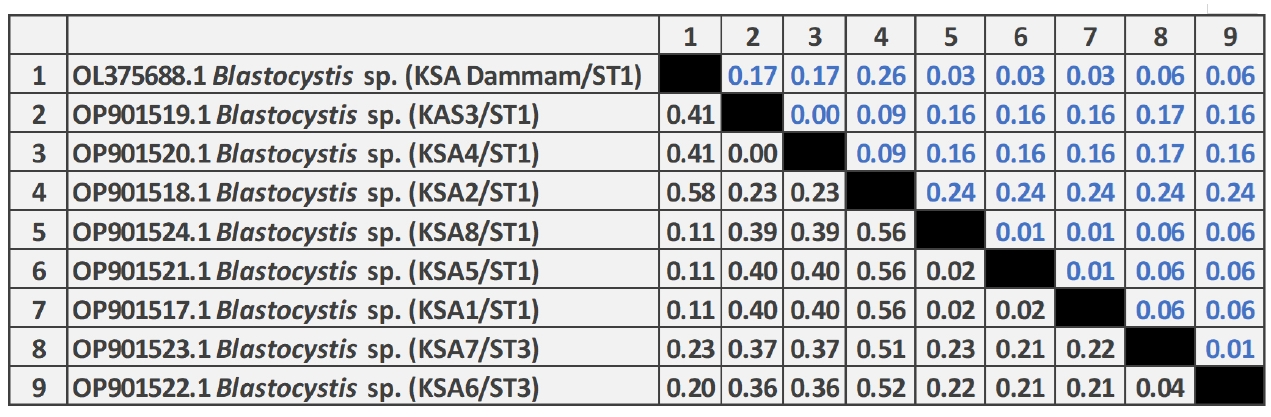

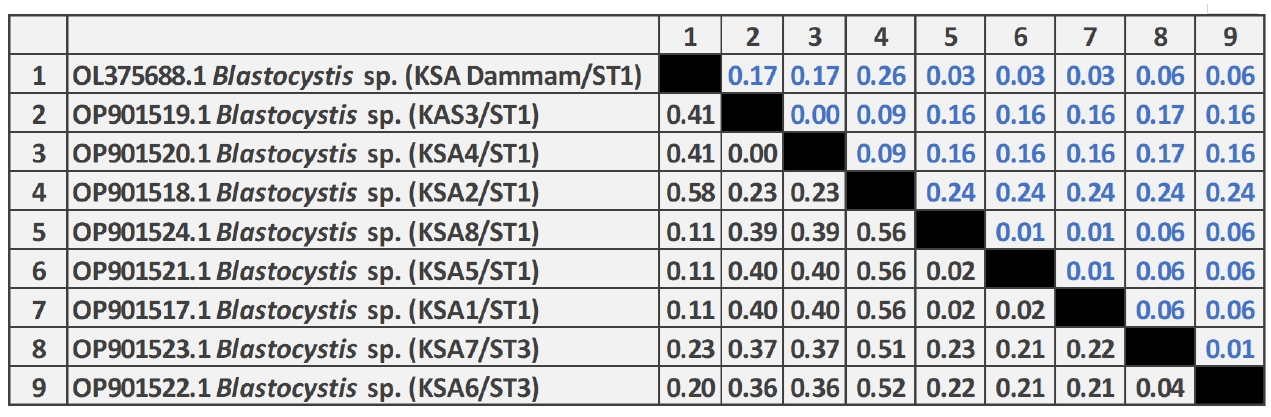

As shown in

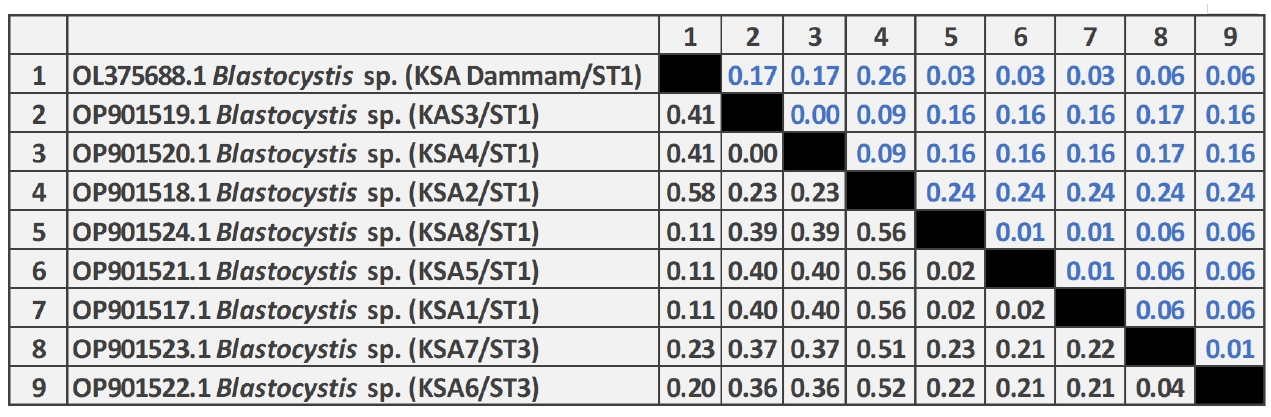

Fig. 3, the pairwise distance of the

Blastocystis sequences obtained in this study revealed that the overall mean distance is 0.25, and between them and the previous Saudi

Blastocystis sequence (OL375688) retrieved from the GenBank database is 0.29. The 8 nucleotide sequences generated in this study have been deposited in GenBank under accession numbers OP901517 to OP901524. The sequence identity of OP901519 and OP901520 was 100% and ranged from 99.4%–99.9% among the remaining 6 sequences.

Discussion

In the current study, 22 out of 34

Blastocystis positive HD participants (64.7%) were complaining of abdominal pain. Regarding other symptoms including diarrhea, nausea and vomiting,

Blastocystis infection was diagnosed more in asymptomatic cases. The pathogenic potential of

Blastocystis remains controversial, as the parasite has been found in both symptomatic and asymptomatic cases in several investigations worldwide [

13-

20].

According to earlier findings, ST1 and ST3 are the STs that are most commonly seen in both humans and animals [

21,

22]. In Saudi Arabia, 4 STs (ST1, ST2, ST3, and ST5) have been detected at varying frequencies using PCR and sequencing in some studies that investigated the occurrence and subtyping of

Blastocystis sp., primarily in Makkah and Taif [

13,

14]. However, using genetic analysis of

Blastocystis isolates, 2 STs of

Blastocystis sp. were identified in this study: ST1 and ST3. Of these, ST1 was the most widely distributed (75%) and ST3 was the least (25%). Previous research in Saudi Arabia [

13], Libya [

21], Turkey [

23], United Arab Emirates [

24], Iran [

25], and Syria [

26], have shown similar results. In contrast, previous studies have reported that the most distributed ST was ST3 followed by ST1 or ST4 [

27-

32]. The high frequency of

Blastocystis ST1 and ST3 infections in Saudi patients shows that the majority of infections are passed between persons. Several previous studies reported that ST1 and ST3 are associated to gastrointestinal symptoms, such as abdominal pain, diarrhoea, vomiting, and flatulence [

3,

20,

26,

29,

33,

34].

In the present study, the genetic analysis showed that the 8 identified isolates correspond to previously observed alleles. Six ST1 isolates produced a high frequency of

Blastocystis isolates matching allele 4, with very low (0.04) genetic divergence. ST3 isolates (

n=2) showed relatively increased genetic diversity (various nucleotide substitution ranged from 0.021 to 0.56) and matching allele 34 (the most common allele worldwide). In Egypt, ST1 and ST2 isolates were found with genetic diversity ranging from 1 to 11 nucleotide substitutions and ST3 isolates were found with low genetic divergence over 4 nucleotide substitutions [

27]. Another study reported that among 11samples analysed, ST1 allele 4, ST2 alleles 9 and 12, and ST3 allele 34 were detected, with ST2 isolates showing low genetic diversity and numerous nucleotide changes [

30].

Phylogenetic analysis of the 18S rRNA gene is useful for characterizing

Blastocystis sp. Eight 18S rRNA sequences from Makkah were identified as

Blastocystis sp. The phylogenetic tree based on 18S rRNA was beneficial in inferring the association between Saudi isolates from diverse regions, with a high bootstrap value. The Saudi isolates in this investigation and those received from GenBank were divided into 4 branches, and the collected isolates were divided into 3 haplotypes, ST1b, ST1c, and ST3. Furthermore, the examination of

Blastocystis sp. 18S rRNA revealed genetic diversity within a single host, with at least 4 groups from different localities (this study and Dammam). This Saudi pattern illustrates how various

Blastocystis genotypes have distinct geographic distributions in patients and exhibit diverse spreads in the Saudi Arabia. A previous study conducted in Egypt found that each

Blastocystis sp. STs constituted a separate clade and that, based on phylogenetic analysis, the 11

Blastocystis sequences grouped into 3 STs (ST1, ST2, and ST3) with strong bootstrap value [

30]. In another study, the same phylogenetic pattern was reported with ST1 and ST3 clusters in patients with irritable bowel syndrome [

35]. The coevolution patterns between the parasite and its host are probably reflected in the phylogenetic analysis of genetically diverse

Blastocystis isolates that differed in their ancestral and epidemiological characteristics.

The current study lacks information regarding environmental or animal contact. Future epidemiological studies are needed to evaluate the influence of environmental factors, animal interactions, and foreign travel history to determine the persistence of Blastocystis.

Notes

-

Author contributions

Conceptualization: Bahwaireth EO, Wakid MH, Alsulami MN, Al-Matary MA. Data curation: Gattan HS, Bahwaireth EO, Wakid MH, Al-Matary MA, El-Kady AM. Formal analysis: Gattan HS, Bahwaireth EO, Wakid MH, Alsulami MN, Al-Matary MA, El-Kady AM. Funding acquisition: Bahwaireth EO. Investigation: Gattan HS, Bahwaireth EO, Wakid MH, Alsulami MN, Al-Matary MA, El-Kady AM. Methodology: Bahwaireth EO, Wakid MH, Alsulami MN, Al-Matary MA. Project administration: Wakid MH. Software: Bahwaireth EO. Supervision: Wakid MH. Writing – original draft: Gattan HS, Bahwaireth EO, Alsulami MN, Al-Matary MA, El-Kady AM. Writing – review & editing: Wakid MH.

-

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

-

Acknowledgments

The authors are very thankful to all the associated personnel for their beneficial help and cooperation.

Fig. 1.Electropherogram of the 1.5% agarose gel showing 385 bp PCR product of the 18S rRNA was successfully amplified for all the samples from hemodialysis patients. Arrow indicates band size. L, ladder.

Fig. 2.Neighbor-joining tree of Blastocystis sp. based on the 18S rRNA nucleotide sequences showing the phylogenetic relationship of Blastocystis sp. collected in Saudi Arabia in the present study (black circles) with other Blastocystis isolates available in GenBank. The tree was constructed using the Kimura-2-parameter model. Bootstrap values are shown at the nodes of branches (1,000 replicates). Each sequence was identified by its GenBank accession number, country, and subtype (ST).

Fig. 3.Pairwise distances between Blastocystis isolates of this study, and Blastocystis sp. (OL375688) partial-length 18S rRNA gene sequence showing the number of base substitutions per site from between sequences. Analyses were conducted using the maximum composite likelihood model and included 9 nucleotide sequences. Codon positions included were 1st+2nd+3rd+noncoding. All positions containing gaps and missing data were eliminated. There was a total of 257 positions in the final dataset.

Table 1.PCR primers specific for 18S rRNA gene of Blastocystis hominis

Table 1.

|

Primer |

Sequence (5’–3’) |

Target Blastocystis subtype |

Specificity |

Annealing temperature (°C) |

Product size (bp) |

|

18S rRNAF |

ACTGCGAATGGCTCATTATAT |

All |

18S rRNA |

54 |

385 |

|

18S rRNAR |

GCATTGTGATTTATTGTCACTACC |

All |

18S rRNA |

54 |

385 |

Table 2.Demographic and gastrointestinal characteristics of the study group

Table 2.

|

Variable |

Hemodialysis patients (n=100) |

Normal control (n=50) |

P-value |

|

Age (yr) |

51.57± 10.5 |

39.66+11.9 |

- |

|

Sex |

Male |

55 |

34 |

0.127 |

|

Female |

45 |

16 |

|

Abdominal pain |

Yes |

62 |

20 |

0.010 |

|

No |

38 |

30 |

|

Nausea |

Yes |

47 |

17 |

0.130 |

|

No |

53 |

33 |

|

Vomiting |

Yes |

29 |

4 |

0.003 |

|

No |

71 |

46 |

|

Diarrhoea |

Yes |

42 |

11 |

0.016 |

|

No |

58 |

39 |

Table 3.

Blastocystis infection among hemodialysis cases and healthy controls according to sex

Table 3.

|

Hemodialysis patients |

Normal control |

|

Female (n=45) |

Male (n=55) |

Total (n=100) |

Female (n=16) |

Male (n=34) |

Total (n=50) |

|

Positive |

13 |

21 |

34 |

7 |

10 |

17 |

|

Negative |

32 |

34 |

66 |

9 |

24 |

33 |

Table 4.Agreement between techniques used to detect Blastocystis hominis, in relation to direct smears, Ritchie technique, and real-time PCR

Table 4.

|

|

|

N |

P |

κ

|

Agreement |

|

Direct smears |

Ritchie technique |

N |

TN103 |

FN14 |

0.764 |

Substantial |

|

P |

FP0 |

TP33 |

|

Real-time PCR |

N |

TN97 |

FN5 |

0.831 |

Perfect |

|

P |

FP6 |

TP42 |

|

Ritchie technique |

Direct smears |

N |

TN103 |

FN0 |

0.764 |

Substantial |

|

P |

FP14 |

TP33 |

|

Real-time PCR |

N |

TN99 |

FN3 |

0.649 |

Substantial |

|

P |

FP18 |

TP30 |

|

Real-time PCR |

Direct smears |

N |

TN97 |

FN6 |

0.831 |

Perfect |

|

P |

FP5 |

TP42 |

|

Ritchie technique |

N |

TN99 |

FN18 |

0.649 |

Substantial |

|

P |

FP3 |

TP30 |

Table 5.Sex and clinical characters of hemodialysis patients

Table 5.

|

Variable |

|

Positive (n=34) |

Negative (n=66) |

P-value |

|

Sex |

Male |

21 |

34 |

0.329 |

|

Female |

13 |

32 |

|

Abdominal pain |

Yes |

22 |

40 |

0.689 |

|

No |

12 |

26 |

|

Nausea |

Yes |

17 |

30 |

0.666 |

|

No |

17 |

36 |

|

Vomiting |

Yes |

10 |

19 |

0.948 |

|

No |

24 |

47 |

|

Diarrhoea |

Yes |

15 |

27 |

0.758 |

|

No |

19 |

39 |

References

- 1. Alqarni AS, Wakid MH, Gattan HS. Prevalence, type of infections and comparative analysis of detection techniques of intestinal parasites in the province of Belgarn, Saudi Arabia. PeerJ 2022;10:e13889. https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.13889

- 2. Nagel R, Traub RJ, Allcock RJ, Kwan MM, Bielefeldt-Ohmann H. Comparison of faecal microbiota in Blastocystis-positive and Blastocystis-negative irritable bowel syndrome patients. Microbiome 2016;4:47. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40168-016-0191-0

- 3. Khademvatan S, Masjedizadeh R, Yousefi-Razin E, et al. PCR-based molecular characterization of Blastocystis hominis subtypes in southwest of Iran. J Infect Public Health 2018;11:43-7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jiph.2017.03.009

- 4. Stensvold CR, Tan KSW, Clark CG. Blastocystis. Trends Parasitol 2020;36:315-6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pt.2019.12.008

- 5. Maloney J, Jang Y, Molokin A, George N, Santin M. Wide genetic diversity of Blastocystis in white-tailed deer (Odocoileus virginianus) from Maryland, USA. Microorganisms 2021;9:1343. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms9061343

- 6. Bahrami F, Babaei E, Badirzadeh A, Rezaeiriabi T, Abdoli A. Blastocystis, urticaria, and skin disorders: review of the current evidences. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 2020;39:1027-42. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10096-019-03793-8

- 7. Parkar U, Traub RJ, Kumar S, et al. Direct characterization of Blastocystis from faeces by PCR and evidence of zoonotic potential. Parasitology 2007;134:359-67. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0031182006001582

- 8. Bahwaireth EO, Wakid MH. Molecular, microscopic, and immunochromatographic detection of enteroparasitic infections in hemodialysis patients and related risk factors. Foodborne Pathog Dis 2022;19:830-8. https://doi.org/10.1089/fpd.2022.0024

- 9. Karadag G, Tamer GS, Dervisoglu E. Investigation of intestinal parasites in dialysis patients. Saudi Med J 2013;34:714-8.

- 10. Omrani VF, Fallahi Sh, Rostami A, et al. Prevalence of intestinal parasite infections and associated clinical symptoms among patients with end-stage renal disease undergoing hemodialysis. Infection 2015;43:537-44. https://doi.org/10.1007/s15010-015-0778-6

- 11. Rasti S, Hassanzadeh M, Hooshyar H, et al. Intestinal parasitic infections in different groups of immunocompromised patients in Kashan and Qom cities, central Iran. Scand J Gastroenterol 2017;52:738-41. https://doi.org/10.1080/00365521.2017.1308547

- 12. Gama NA, Adami YL, Lugon JR. Assessment of Blastocystis spp. infection in hemodialysis patients in two centers of the metropolitan area of Rio de Janeiro. J Kidney Treat Diagn 2018;1:49-52.

- 13. Mohamed RT, El-Bali MA, Mohamed AA, et al. Subtyping of Blastocystis sp. isolated from symptomatic and asymptomatic individuals in Makkah, Saudi Arabia. Parasit Vectors 2017;10:174. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13071-017-2114-8

- 14. Wakid MH, Aldahhasi WT, Alsulami MN, El-Kady AM, Elshabrawy HA. Identification and genetic characterization of Blastocystis species in patients from Makkah, Saudi Arabia. Infect Drug Resist 2022;15:491-501. https://doi.org/10.2147/IDR.S347220

- 15. Aldahhasi WT, Toulah FH, Wakid MH. Evaluation of common microscopic techniques for detection of Blastocystis hominis. J Egypt Soc Parasitol 2020;50:33-40. https://doi.org/10.21608/JESP.2020.88748

- 16. Abdulsalam AM, Ithoi I, Al-Mekhlafi HM, et al. Prevalence, predictors and clinical significance of Blastocystis sp. in Sebha, Libya. Parasit Vectors 2013;6:86. https://doi.org/10.1186/1756-3305-6-86

- 17. Shehab A, El-Sayad M, Allam A, et al. Insights into the association between Blastocystis infection and colorectal cancer. Acta Parasitol 2025;70:156. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11686-025-01079-y

- 18. Ahmed HK, Mohamed KA, Sheishaa GAA, et al. Blastocystis SPP. infection prevalence and associated patient characteristics as predictors among a cohort of symptomatic and asymptomatic Egyptians. Int J Health Sci 2022;6:5839-52. https://doi.org/10.53730/ijhs.v6nS6.10918

- 19. Sylla K, Sow D, Lelo S, et al. Blastocystis sp. infection: prevalence and clinical aspects among patients attending to the laboratory of parasitology-mycology of Fann University Hospital, Dakar, Senegal. Parasitologia 2022;2:292-301. https://doi.org/10.3390/parasitologia2040024

- 20. Kaneda Y, Horiki N, Cheng XJ, et al. Ribodemes of Blastocystis hominis isolated in Japan. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2001;65:393-6. https://doi.org/10.4269/ajtmh.2001.65.393

- 21. Abdulsalam AM, Ithoi I, Al-Mekhlafi HM, et al. Subtype distribution of Blastocystis isolates in Sebha, Libya. PLoS One 2013;8:e84372. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0084372

- 22. Stensvold CR, Clark CG. Current status of Blastocystis: a personal view. Parasitol Int 2016;65:763-71. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.parint.2016.05.015

- 23. Eroglu F, Genc A, Elgun G, Koltas IS. Identification of Blastocystis hominis isolates from asymptomatic and symptomatic patients by PCR. Parasitol Res 2009;105:1589-92. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00436-009-1595-6

- 24. AbuOdeh R, Ezzedine S, Samie A, Stensvold CR, ElBakri A. Prevalence and subtype distribution of Blastocystis in healthy individuals in Sharjah, United Arab Emirates. Infect Genet Evol 2016;37:158-62. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.meegid.2015.11.021

- 25. Taghipour A, Javanmard E, Mirjalali H, et al. Blastocystis subtype 1 (allele 4); predominant subtype among tuberculosis patients in Iran. Comp Immunol Microbiol Infect Dis 2019;65:201-6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cimid.2019.06.005

- 26. Darwish B, Aboualchamat G, Al Nahhas S. Molecular characterization of Blastocystis subtypes in symptomatic patients from the southern region of Syria. PLoS One 2023;18:e0283291. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0283291

- 27. Souppart L, Moussa H, Cian A, et al. Subtype analysis of Blastocystis isolates from symptomatic patients in Egypt. Parasitol Res 2010;106:505-11. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00436-009-1693-5

- 28. Greige S, El Safadi D, Khaled S, et al. First report on the prevalence and subtype distribution of Blastocystis sp. in dairy cattle in Lebanon and assessment of zoonotic transmission. Acta Trop 2019;194:23-9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actatropica.2019.02.013

- 29. Gulhan B, Aydin M, Demirkazik M, et al. Subtype distribution and molecular characterization of Blastocystis from hemodialysis patients in Turkey. J Infect Dev Ctries 2020;14:1448-54. https://doi.org/10.3855/jidc.12650

- 30. Ahmed SA, El-Mahallawy HS, Mohamed SF, et al. Subtypes and phylogenetic analysis of Blastocystis sp. isolates from West Ismailia, Egypt. Sci Rep 2022;12:19084. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-23360-0

- 31. Hatalová E, Babinská I, Gočálová A, Urbančíková I. Molecular screening for enteric parasites and subtyping of Blastocystis sp. in haemodialysis patients in Slovakia. Ann Agric Environ Med 2024;31:193-7. https://doi.org/10.26444/aaem/185634

- 32. Abdellatif MZM, Abdel-Hafeez EH, Belal US, et al. Detection of Blastocystis species in immunocompromised patients (cancer, diabetes mellitus, and chronic renal diseases) by restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP). Beni-Suef Univ J Basic Appl Sci 2025;14:42. https://doi.org/10.1186/s43088-025-00631-z

- 33. El Safadi D, Meloni D, Poirier P, et al. Molecular epidemiology of Blastocystis in Lebanon and correlation between subtype 1 and gastrointestinal symptoms. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2013;88:1203-6. https://doi.org/10.4269/ajtmh.12-0777

- 34. Matovelle C, Quílez J, Tejedor MT, et al. Subtype distribution of Blastocystis spp. in patients with gastrointestinal symptoms in Northern Spain. Microorganisms 2024;12:1084. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms12061084

- 35. El-Badry AA, Abd El Wahab WM, Hamdy DA, Aboud A. Blastocystis subtypes isolated from irritable bowel syndrome patients and co-infection with Helicobacter pylori. Parasitol Res 2018;117:127-37. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00436-017-5679-4

, Ebtihal O. Bahwaireth3

, Ebtihal O. Bahwaireth3 , Majed H. Wakid1,2,*

, Majed H. Wakid1,2,* , Muslimah N. Alsulami4

, Muslimah N. Alsulami4 , Mohammed A. Al-Matary5,6

, Mohammed A. Al-Matary5,6 , Asmaa M. El-Kady7

, Asmaa M. El-Kady7