Abstract

Helminth-mediated immunomodulation has been extensively studied in animal models, demonstrating its potential as both a prophylactic and therapeutic option for inflammatory lung diseases. However, its role in attenuating respiratory virus-induced inflammation remains largely unexplored. In this study, we examined whether pre-existing infection with the helminth Trichinella spiralis confers protection against pulmonary pathology induced by respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) infection in mice. Mice with prior T. spiralis infection exhibited reduced pulmonary inflammation and lower viral titers in the lungs compared with RSV-infected controls. Transcriptomic profiling of lung tissue using RNA sequencing identified 407 differentially expressed genes. Among these, enrichment was observed in categories associated with the Gene Ontology (GO) terms “inflammatory response” (GO:0006954) and “defense response to virus” (GO:0051607). Selected genes from these categories were further validated by quantitative real-time PCR. Validation confirmed that co-exposure to T. spiralis and RSV resulted in attenuated expression of inflammation-related genes. Collectively, these findings demonstrate that pre-existing T. spiralis infection can alleviate virus-induced pulmonary pathology and inflammation, highlighting its potential as a novel therapeutic approach for respiratory inflammatory diseases.

-

Key words: Immunomodulation, inflammation, respiratory syncytial viruses, Trichinella spiralis

Introduction

Helminths are a diverse group of large multicellular organisms, including nematodes, cestodes, and trematodes, that have co-evolved with humans over millennia. Although many helminths are parasitic and their presence within the human body can be deleterious, these organisms have developed versatile immunomodulatory strategies that enable long-term persistence while minimizing host tissue damage [

1]. Globally, an estimated 2 billion individuals, predominantly in impoverished tropical and subtropical regions, are infected with helminths, whereas their prevalence has markedly declined in industrialized nations [

2]. However, growing evidence indicates that improvements in sanitation and widespread deworming have been accompanied by unintended consequences, particularly a rise in allergic and inflammatory disorders [

3]. One early epidemiological study reported a significantly lower prevalence of allergic diseases in rural communities co-exposed to bacterial, viral, and helminthic pathogens compared with urban populations living under hygienic conditions [

4]. These observations contributed to the formulation of the “hygiene hypothesis” in the late 1980s, which posited that reduced exposure to parasitic infections during early life results in insufficient immune stimulation, thereby increasing susceptibility to allergic and autoimmune diseases that are highly prevalent in developed countries [

5]. Supporting this hypothesis, helminth-induced amelioration of inflammatory and autoimmune diseases has been documented in humans. For instance, patients with multiple sclerosis who harbored intestinal parasitic infections exhibited fewer disease exacerbations and reduced pathological changes compared with uninfected controls [

6]. Similarly, colonization of the intestine by

Trichuris trichiura promoted a Th2-skewed immune response that alleviated ulcerative colitis through mechanisms involving increased mucus secretion and goblet cell hyperplasia [

7]. These findings suggest that helminths, or antigens derived from them, may serve as promising candidates for the development of novel therapeutic strategies against autoimmune and inflammatory diseases, thereby warranting further investigations of individual species with distinct immunomodulatory properties.

Trichinella spiralis is a helminth well recognized for its immunomodulatory and anti-inflammatory properties across a wide range of diseases. For example, serine protease inhibitors secreted by

T. spiralis muscle larvae have been shown to inactivate the NF-κB signaling cascade, thereby ameliorating tissue damage associated with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease [

8]. Similarly,

T. spiralis infection alleviated vincristine-induced peripheral neuropathy in mice by suppressing neuroinflammation [

9]. Importantly, the immunomodulatory effects of

T. spiralis are not restricted to autoimmune conditions but extend to infections with co-inhabiting pathogens, as demonstrated in experimental models of respiratory disease. Worm extracts derived from

T. spiralis have been reported to attenuate sepsis-induced acute lung injury in mice [

10]. Moreover, pre-existing

T. spiralis infection in C57BL/6 mice promoted a Th2-biased immune response, which reduced neutrophil recruitment and the influx of proinflammatory cytokines following

Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection [

11]. In another study, excretory–secretory antigens of

T. spiralis exerted protective effects against coronavirus infection in mice [

12]. Chronic

T. spiralis infection was also shown to dampen allergic airway remodeling induced by exposure to house dust mite allergens [

13], highlighting its therapeutic potential in modulating host immune responses to inflammatory disorders.

Consistent with previous findings demonstrating the ability of

T. spiralis to mitigate inflammatory responses, our earlier work showed that

T. spiralis infection attenuates pulmonary inflammation induced by respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) exposure in mice [

14]. Despite our previous histopathological and cytokine-level analyses demonstrating that

T. spiralis infection suppresses RSV-induced inflammation, the molecular pathways and cellular networks underlying this protective effect remain undefined. To address this gap, we performed RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) to identify the host genetic factors underlying these protective effects and to obtain a comprehensive overview of gene-expression changes associated with

T. spiralis-mediated modulation of RSV pathogenesis. This systems-level approach enables the unbiased identification of immunoregulatory pathways including cytokine signaling cascades and interferon-stimulated genes that are not readily discernible through conventional assays. By integrating differential gene-expression profiles with pathway and network analyses, we sought to delineate how

T. spiralis-induced regulatory programs reshape antiviral and inflammatory responses in the lung. These transcriptomic insights extend beyond prior phenotypic observations and provide a mechanistic framework for the development of novel immunomodulatory strategies for virus-induced pulmonary diseases.

Methods

Ethics statement

All experiments involving animals were approved by Kyung Hee University’s Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (accession No. KHUASP-SE-22). Mice were housed in an institution-approved facility under specific-pathogen-free conditions. Mice were randomly assigned to experimental groups and maintained under controlled environmental conditions with standard enrichment, a 12 h light/dark cycle, and ad libitum access to food and water. All experimental procedures were conducted in accordance with institutional guidelines for animal care and welfare. Efforts were made to minimize animal suffering, and mice exhibiting signs of severe distress were humanely euthanized by CO₂ inhalation followed by cervical dislocation.

Cell, parasites, and virus culture

T. spiralis muscle larvae were serially passaged in Sprague–Dawley rats and recovered using an artificial digestion method, as previously described [

15]. Briefly, skeletal muscles from infected rats were digested in a pepsin–HCl solution, and released larvae were filtered through a wire mesh to remove residual tissue debris. The sedimented larvae were washed repeatedly with 0.85% saline until the supernatant became clear, after which they were enumerated microscopically prior to infection. RSV was propagated in HEp-2 cells and titrated by plaque assay, as previously described [

16]. Confluent HEp-2 cell monolayers were infected with the RSV A2 strain at a multiplicity of infection of 0.1 in serum-free DMEM (Welgene) and incubated for 48 h at 37°C in 5% CO₂. Upon observation of cytopathic effects, cells were harvested using a cell scraper and centrifuged at 2,000 rpm for 5 min at 4°C. The supernatant was discarded, and the cell pellet was sonicated to release progeny virus. Following titration, virus stocks were aliquoted and stored at -80°C until use.

Experimental infection of mice, lung tissue sampling, and RNA preparation

BALB/c mice were obtained from NARA Biotech and assigned to 1 of 4 groups (n=6 per group): infection with 400 T. spiralis muscle larvae (Ts), infection with 3×10⁶ plaque-forming units of RSV, co-infection with both pathogens (Ts-RSV), or uninfected naïve controls. T. spiralis larvae were administered via orogastric tube on day 0, whereas RSV was delivered intranasally on day 12. All mice were sacrificed on day 16, and whole lung tissues were collected. Lungs were homogenized, and total RNA was extracted using the RNeasy Kit (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. RNA concentration and purity were assessed with a NanoDrop One spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific), and samples were stored at -80°C until further use. Whole lung tissue from 1 representative mouse in each experimental group was used for RNA-seq, while lung tissues from the remaining 5 mice were used for other downstream assays.

Quantifying lung RSV titer, hematoxylin and eosin staining of lung tissues

Mice were sacrificed for lung virus titer quantification and histopathological analysis. Half of the left lobes were homogenized and processed for plaque assay, while the remaining half were prepared for hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining. For plaque assays, lung tissues were homogenized in cold phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and filtered through a cell strainer. Homogenates were centrifuged at 3,000 rpm for 5 min at 4°C, and the supernatants were collected. HEp-2 cells were seeded in 12-well culture plates and grown to confluence in complete DMEM (Welgene) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and 1% penicillin–streptomycin at 37°C in 5% CO₂. After aspirating the culture medium, cells were washed with PBS and incubated with serially diluted lung supernatants in serum-free DMEM for 1 h at 37°C. Following viral adsorption, the inoculum was removed and cells were overlaid with 1% noble agar. Plates were incubated for 3 days at 37°C in 5% CO₂ until plaques developed. After incubation, agar overlays were carefully removed, and cells were fixed in a methanol–acetone solution (1:1) for 20 min at room temperature. Wells were blocked with 5% skim milk in PBS containing 0.1% Tween-20 for 1 h at room temperature. Monoclonal antibodies specific for the RSV fusion protein (Merck Millipore) diluted in PBS were added and incubated for 1 h at 37°C, followed by horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-mouse IgG secondary antibodies. Plaques were visualized by adding 3,3′-diaminobenzidine (Invitrogen), and viral titers were determined by plaque counting. For histopathological evaluation, the lung tissues were immersed in 10% neutral-buffered formalin, paraffin-embedded, and sectioned using a microtome. Tissue sections were stained with H&E, and immune cell infiltration and inflammatory severity were assessed microscopically at 100× magnification.

RNA-seq via Massive Analysis of cDNA Ends, data analysis, and pathway mapping

Total RNA was extracted from the whole lungs of 1 representative mouse per group and subjected to RNA sequencing. The resulting transcriptomic profiles were used for exploratory comparison of gene-expression patterns among groups. RNA-seq and data analysis was performed by Ebiogen. For control and test RNAs, the construction of library was performed using QuantSeq 3’mRNA-Seq Library Prep Kit (Lexogen) following the manufacturer’s instructions. In brief, each 500 ng total RNA were prepared and an oligo-dT primer containing an Illumina-compatible sequence at its 5’end was hybridized to the RNA and reverse transcription was performed. After degradation of the RNA template, second strand synthesis was initiated by a random primer containing an Illumina-compatible linker sequence at its 5’end. The double-stranded library was purified using magnetic beads to remove all reaction components. The library was amplified to add the complete adapter sequences required for cluster generation. The finished library is purified from PCR components. High-throughput sequencing was performed as single-end 75 sequencing using NextSeq 500 (Illumina). For data analysis, QuantSeq 3’mRNA-Seq reads were aligned using Bowtie2. Bowtie2 indices were either generated from genome assembly sequence or the representative transcript sequences for aligning to the genome and transcriptome. The alignment file was used for assembling transcripts, estimating their abundances and detecting differential expression of genes. Differentially expressed genes (DEGs) were determined based on counts from unique and multiple alignments using coverage in BEDTools. The read count data were processed based on quantile normalization method using EdgeR within R using Bioconductor [

17]. Gene classification was based on searches done by the Database for Annotation, Visualization and Integrated Discovery (

https://davidbioinformatics.nih.gov/) and Medline databases (

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/). Data mining and graphic visualization were performed using the Excel-based Differentially Expressed Gene Analysis (ExDEGA; Ebiogen). Raw reads were processed using the ExDEGA pipeline (Ebiogen) and aligned to the

Mus musculus reference genome (mm10, GRCm38 assembly) obtained from the UCSC Genome Browser database. Genes showing an absolute twofold or greater change in expression with a false discovery rate of less than 0.05 were considered differentially expressed. The Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway for “

mmu04060: Cytokine-cytokine receptor interaction” was obtained from the KEGG database [

18]. DEGs identified by RNA-seq were mapped onto this pathway using KEGG Mapper, and nodes were color-coded according to up regulation or downregulation based on the

T. spiralis plus RSV (Ts-RSV) versus RSV comparison.

Mice from each experimental group were sacrificed for lung tissue collection, and total RNA was extracted from the right lungs for quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR). cDNA was synthesized using the PrimeScript First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (Takara) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. qPCR was performed on a Mic qPCR cycler (PhileKorea). Each 20 μl reaction mixture contained 10 μl of Luna Universal qPCR Master Mix (New England Biolabs), 1 μl each of forward and reverse primers, and 20 ng of cDNA template. The thermal cycling protocol consisted of an initial denaturation at 95°C for 2 min, followed by 40 cycles of 95°C for 15 sec and 60°C for 60 sec. Relative mRNA expression levels of C-X-C motif chemokine ligands 9–10 (

Cxcl9,

Cxcl10, and

Cxcl11), serum amyloid A3 (

Saa3), and tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase 1 (

Timp1) were calculated using the comparative cycle threshold method. Gene expressions were normalized to beta-actin (

Actb). The primer sequences for all genes used in this study are listed in

Table 1.

Statistical significance was calculated using the GraphPad Prism 8 software. Data were presented as mean±SD and significance between the groups were determined using either a one-way analysis of variance with Tukey's post hoc tests or two-tailed Student's t-test. Significant differences between the means were denoted with an asterisk and P<0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Pre-existing T. spiralis enhances antiviral immunity and attenuates RSV-induced pulmonary inflammation in mice

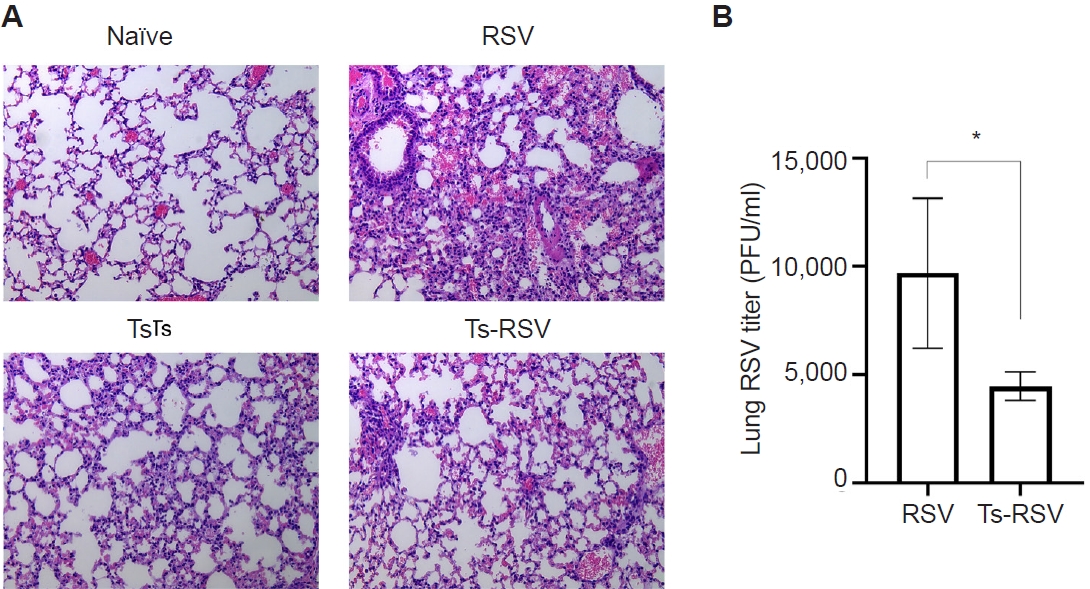

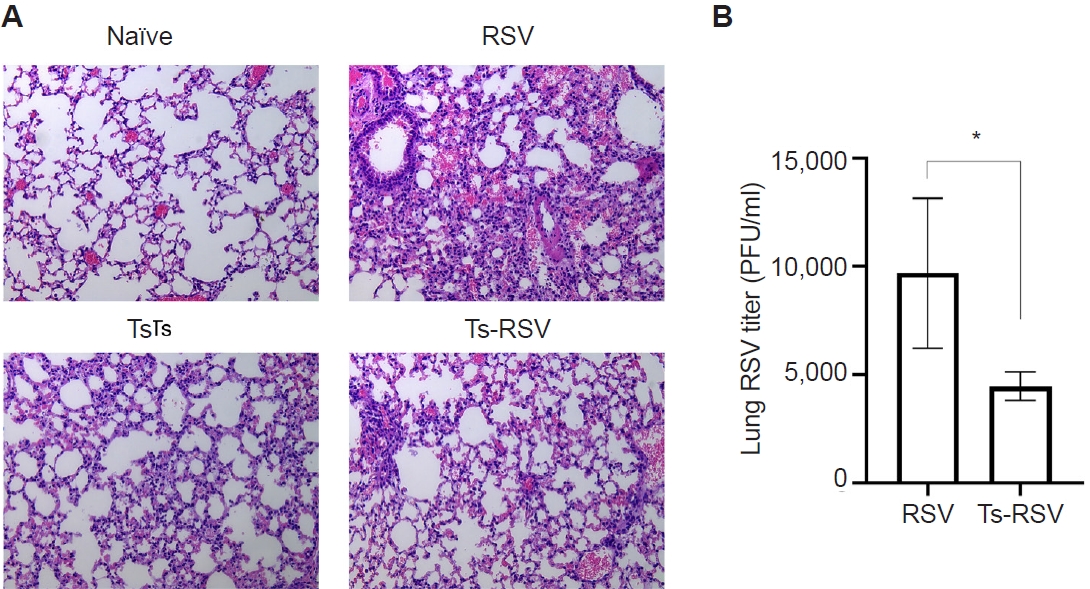

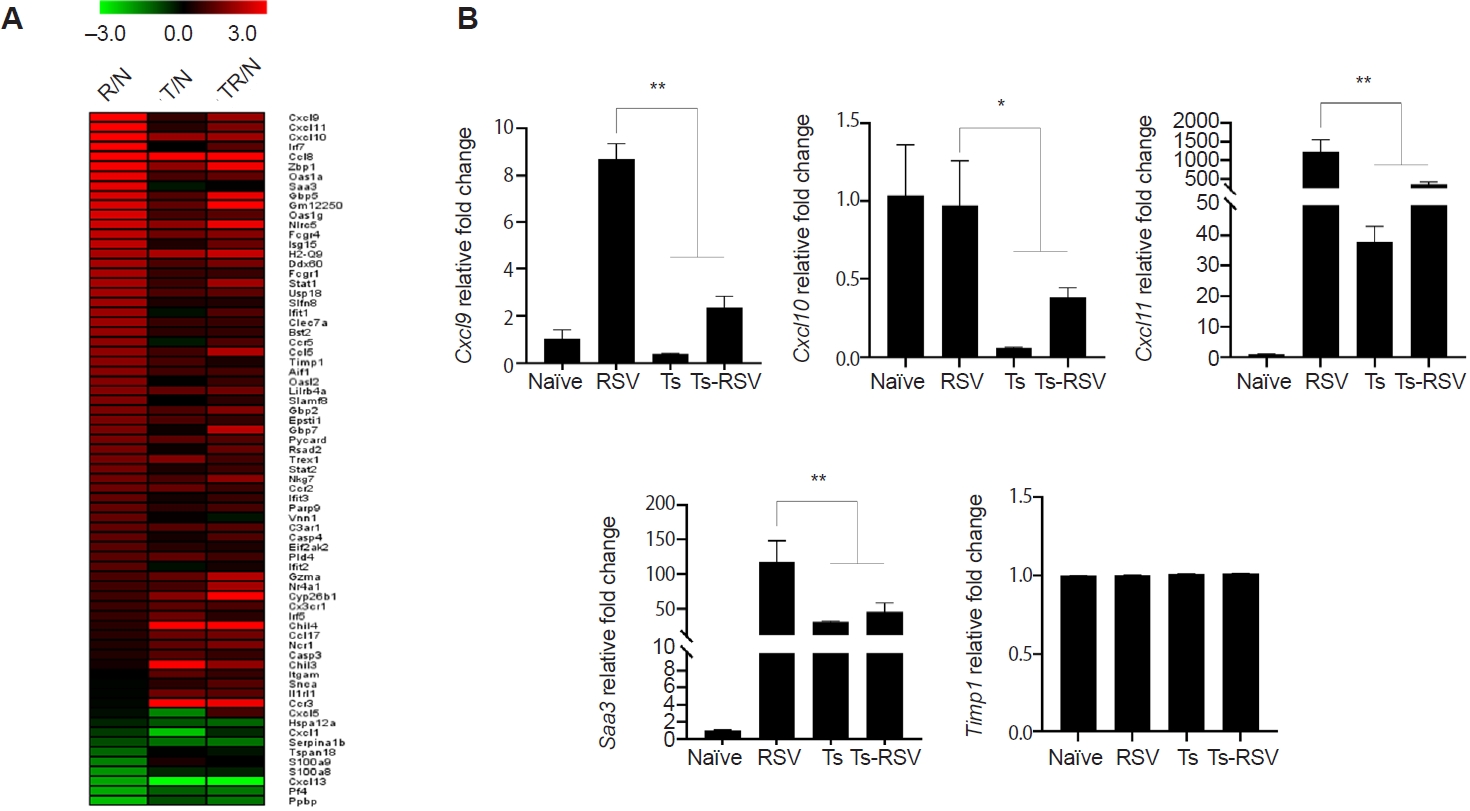

To validate the protective effects of

T. spiralis against RSV infection, lung viral titers and histopathological analyses were performed. As expected, extensive immune cell infiltration was not observed in the lungs of naïve mice (

Fig. 1A). Mice with pre-existing

T. spiralis infection exhibited only mild inflammatory responses, characterized by limited immune cell recruitment. In contrast, RSV-infected mice displayed marked pulmonary inflammation with pronounced cellular influx, which was substantially reduced in mice co-infected with

T. spiralis and RSV. To further assess whether

T. spiralis infection limits viral replication in the lungs, plaque assays were conducted (

Fig. 1B). Compared with RSV-infected controls, mice with prior

T. spiralis exposure demonstrated a significant reduction in lung viral titers. Collectively, these findings confirm that pre-existing

T. spiralis infection alleviates RSV-induced pulmonary inflammation and suppresses viral propagation in the lungs.

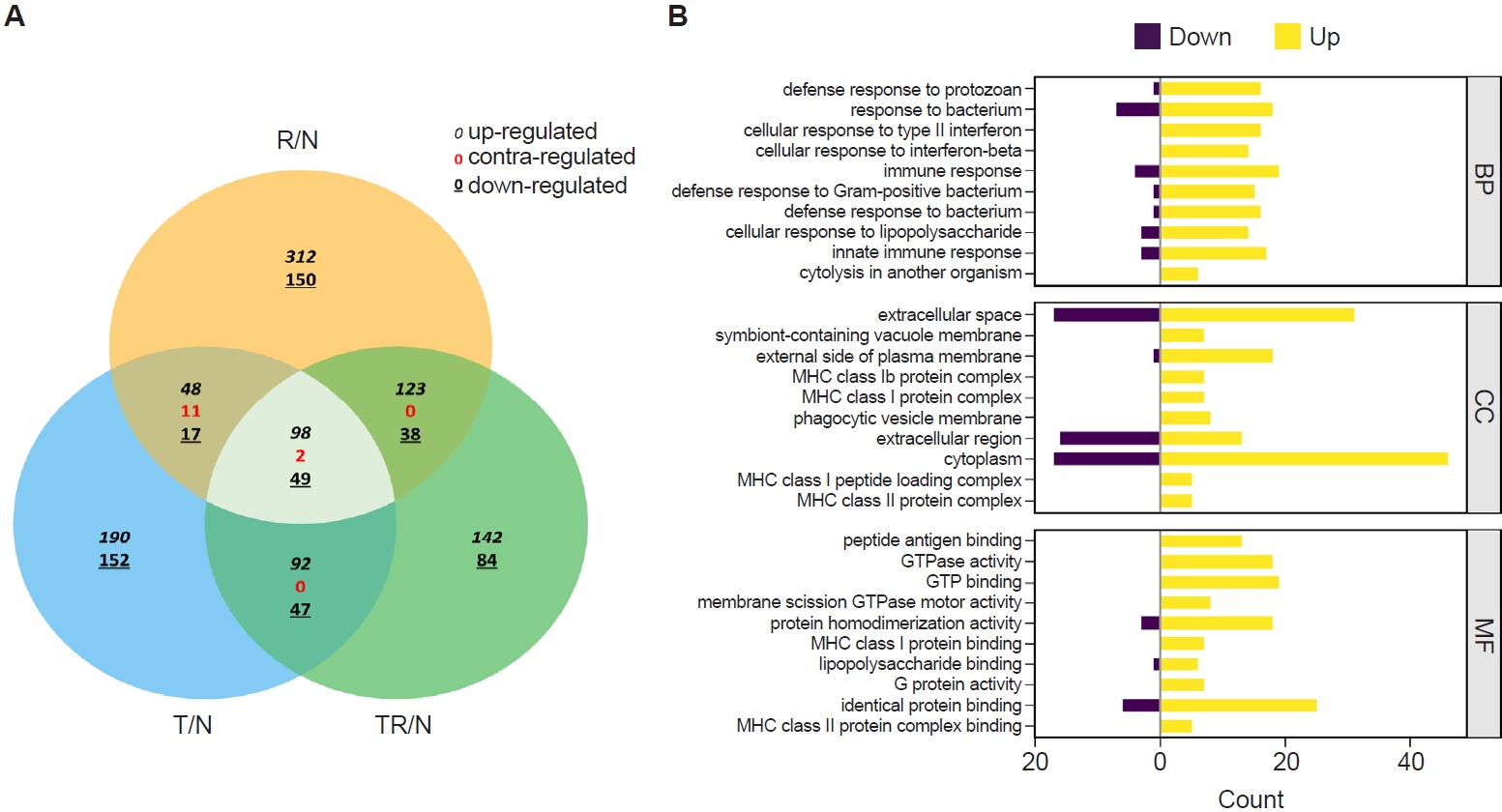

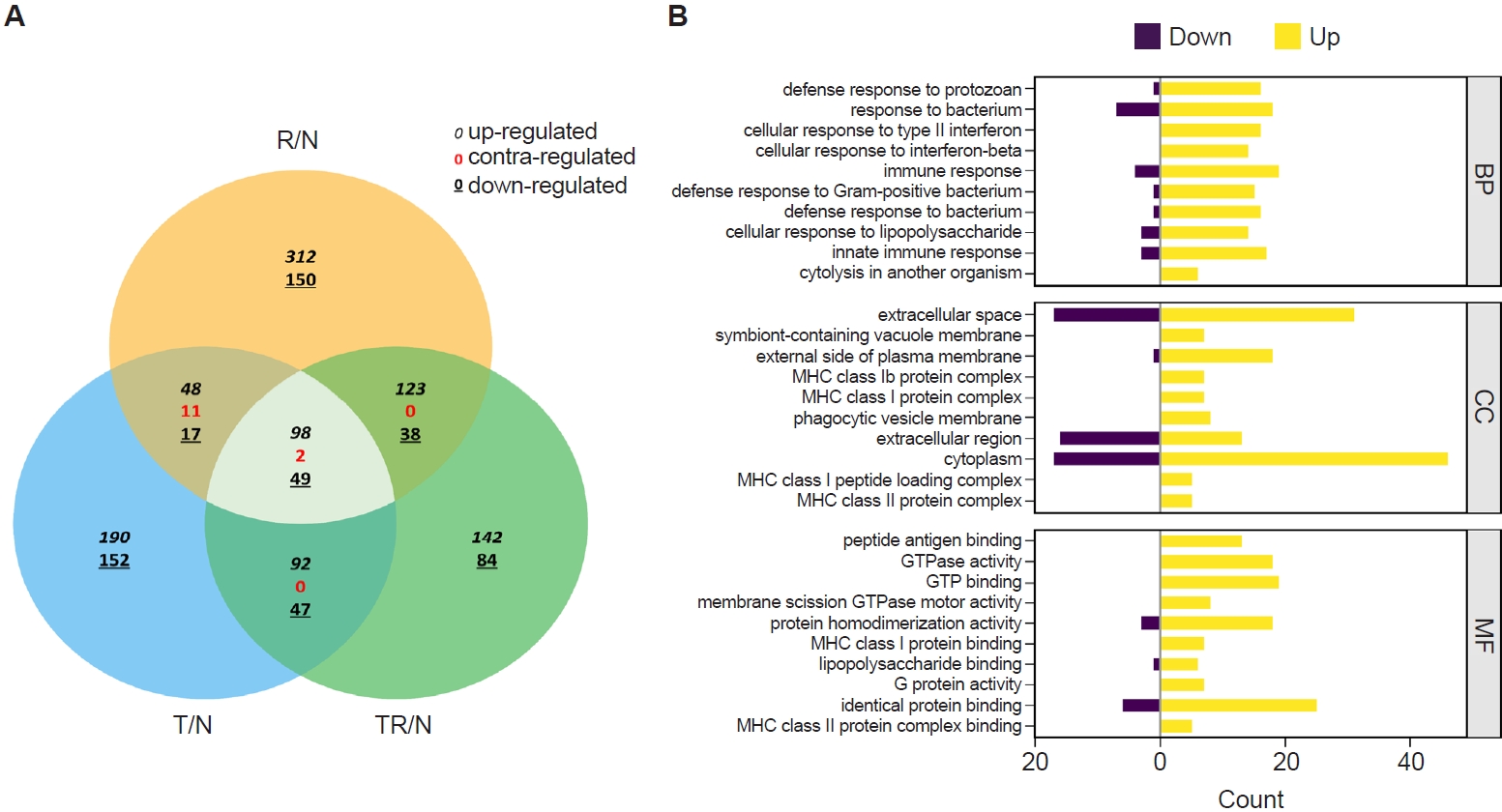

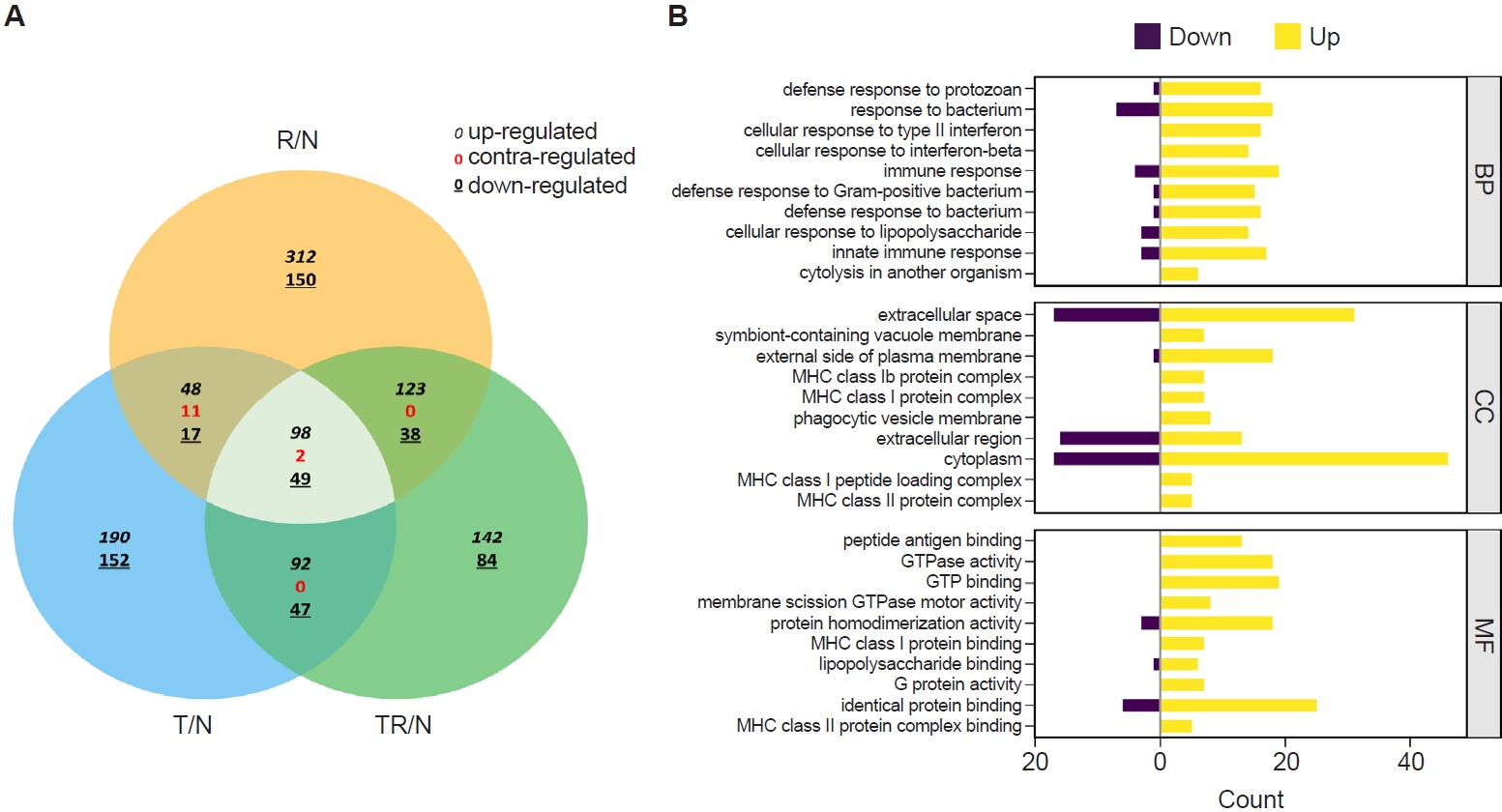

RNA sequencing was performed to identify

T. spiralis-induced alterations in pulmonary gene expression that may contribute to protection against subsequent RSV infection. Gene expression profiles from infected mice were normalized to those of naïve controls and designated as R/N (RSV vs. naïve), T/N (

T. spiralis vs. naïve), and TR/N (co-infection vs. naïve). A total of 23,282 genes were detected, of which 407 were DEGs exhibiting ≥2-fold changes. A Venn diagram depicting upregulated, downregulated, and contra-regulated DEGs is shown in

Fig. 2A. Notably, no contra-regulated genes were identified between T/N and TR/N or between R/N and TR/N, whereas 11 contra-regulated genes were detected between T/N and R/N. Next, fold enrichment analysis was performed for the TR/N group (

Fig. 2B). DEGs were categorized into the 3 principal Gene Ontology (GO) domains: Biological Process, Cellular Component, and Molecular Function. The top 10 upregulated and downregulated pathways were identified for each domain. Among these, the most strongly regulated category was “cytoplasm” within the Cellular Component domain, which contained both the highest upregulated and downregulated genes.

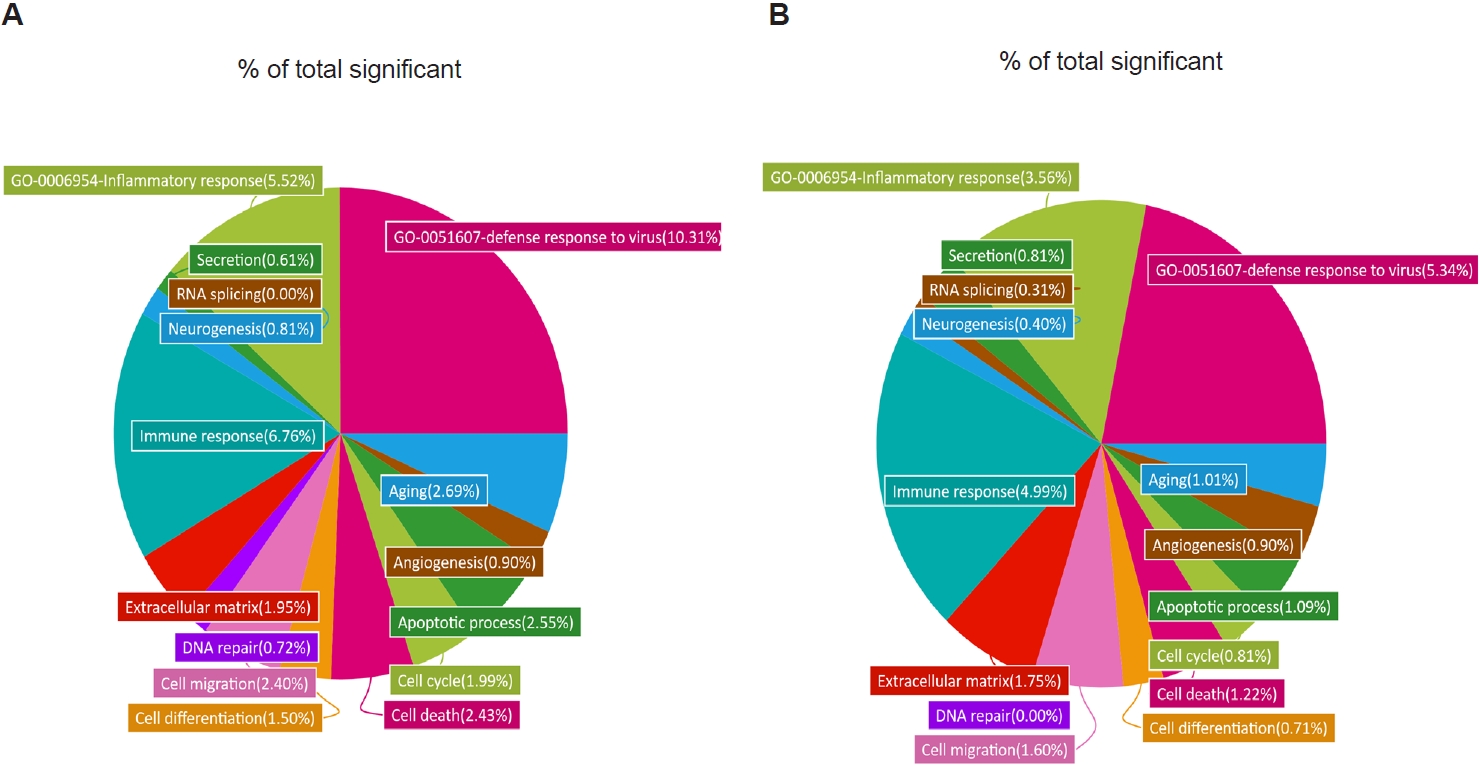

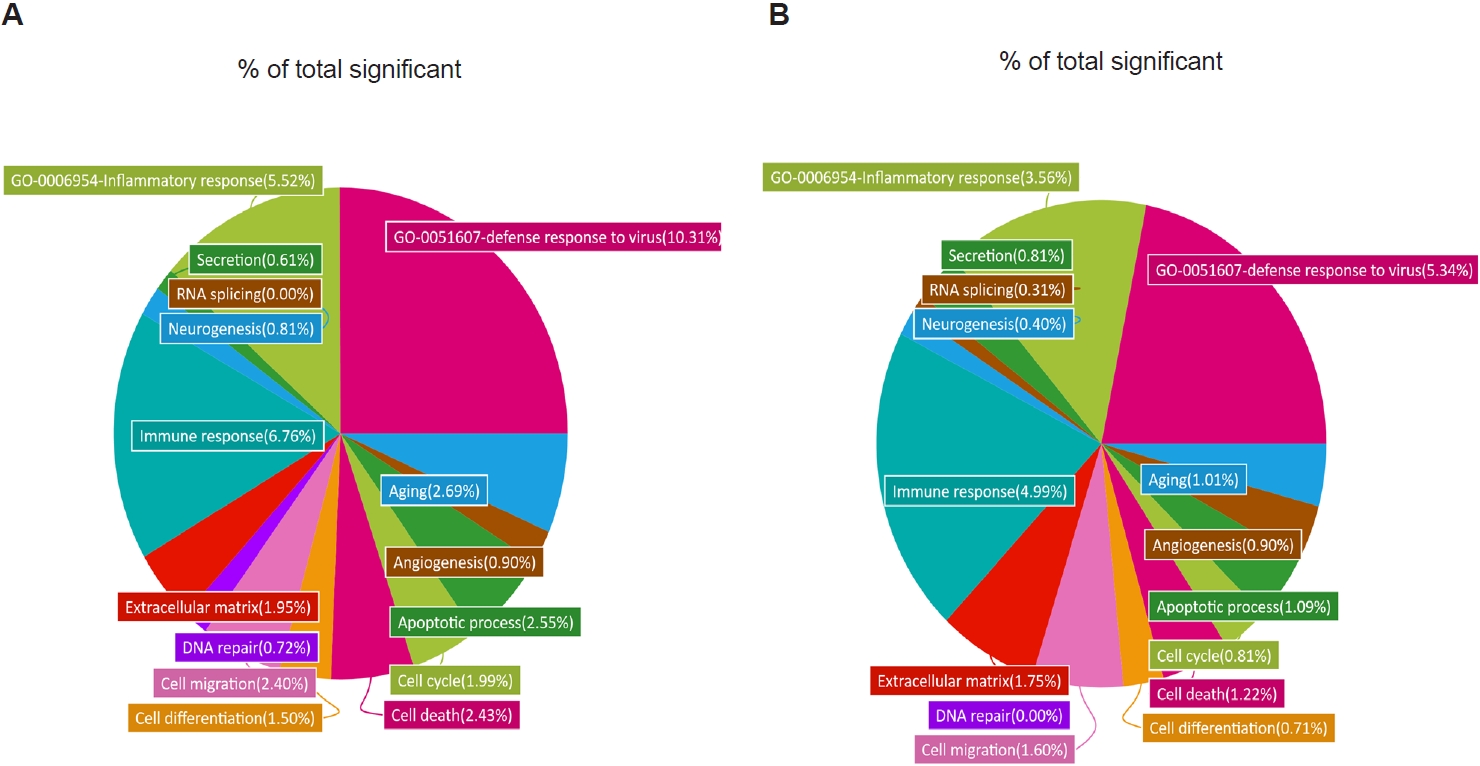

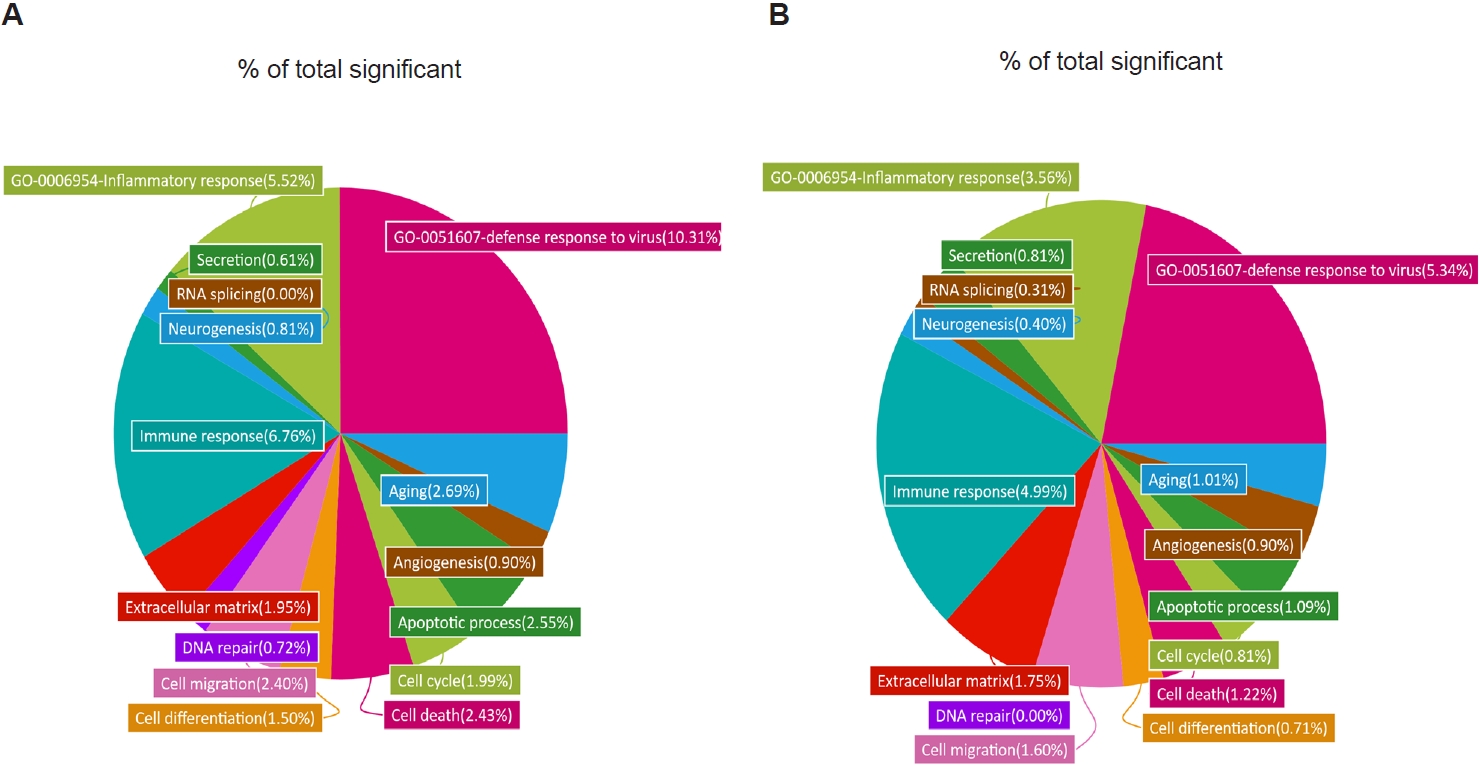

To further characterize these transcriptional changes, we analyzed the distribution of DEGs across GO categories in R/N and TR/N (

Fig. 3A,

B). Because our focus was on

T. spiralis-induced pathways associated with reduced pulmonary inflammation and viral load, 2 GO terms of particular relevance were included: “inflammatory response” (GO:0006954) and “defense response to virus” (GO:0051607). In RSV-infected mice, these categories accounted for 10.31% and 5.52% of all significant DEGs, respectively. By contrast, in the TR/N group, these proportions were reduced approximately by half, to 5.34% and 3.56%. Additional decreases in DEG proportions were observed in categories such as aging, cell differentiation, and cell cycle. Conversely, increases were detected in GO terms associated with secretion and RNA splicing, while angiogenesis-related DEGs remained unchanged between R/N and TR/N.

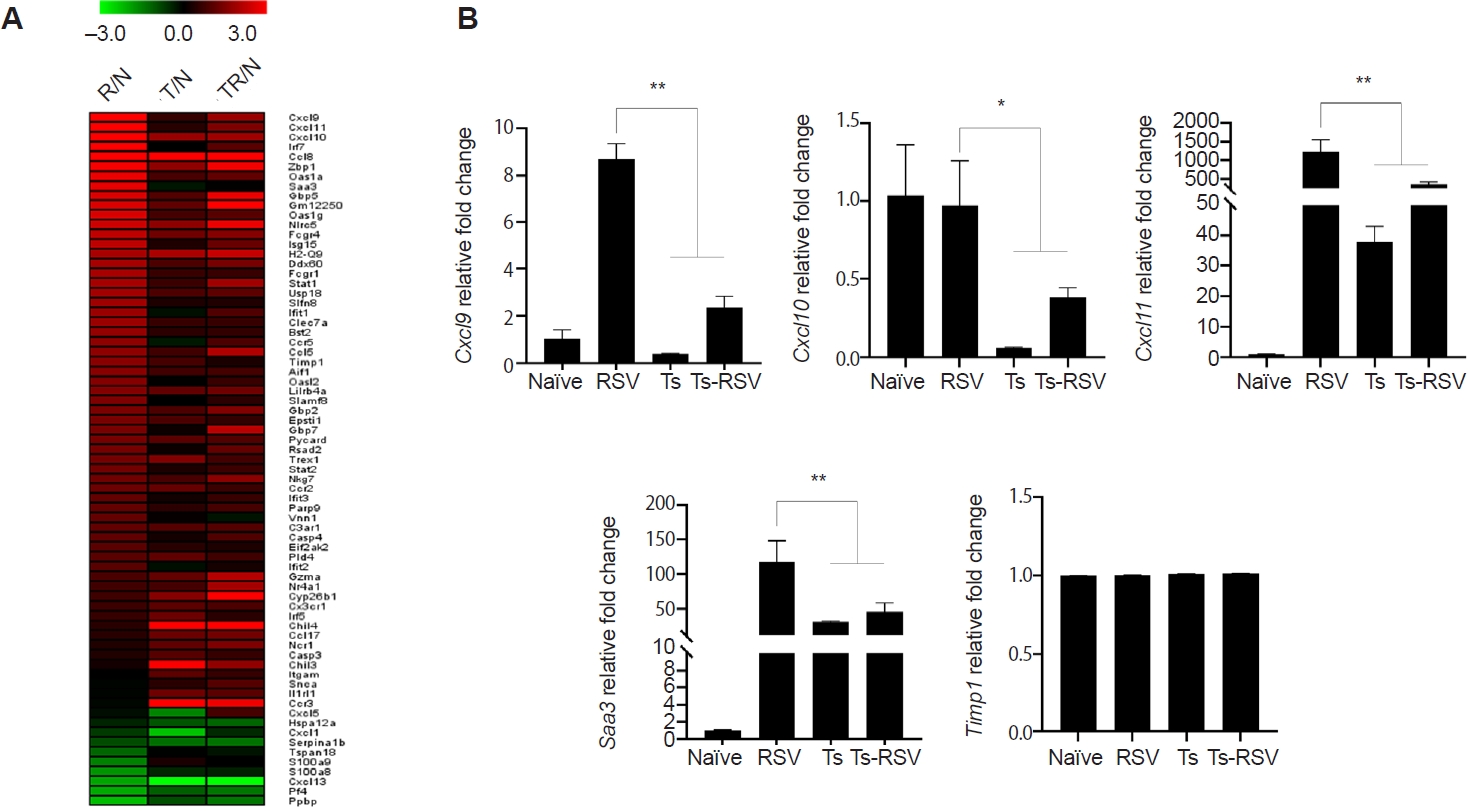

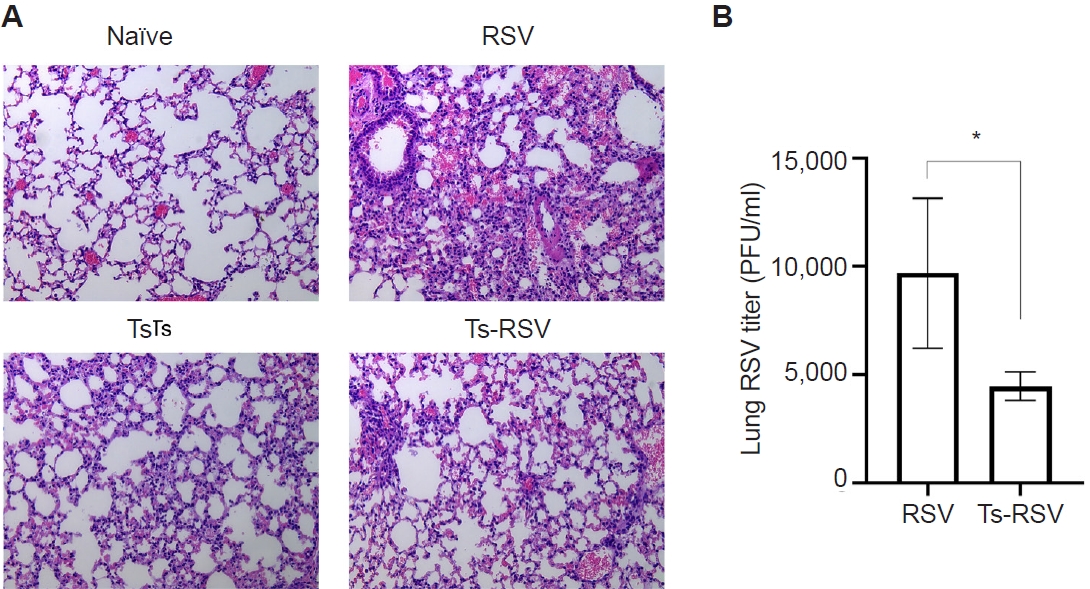

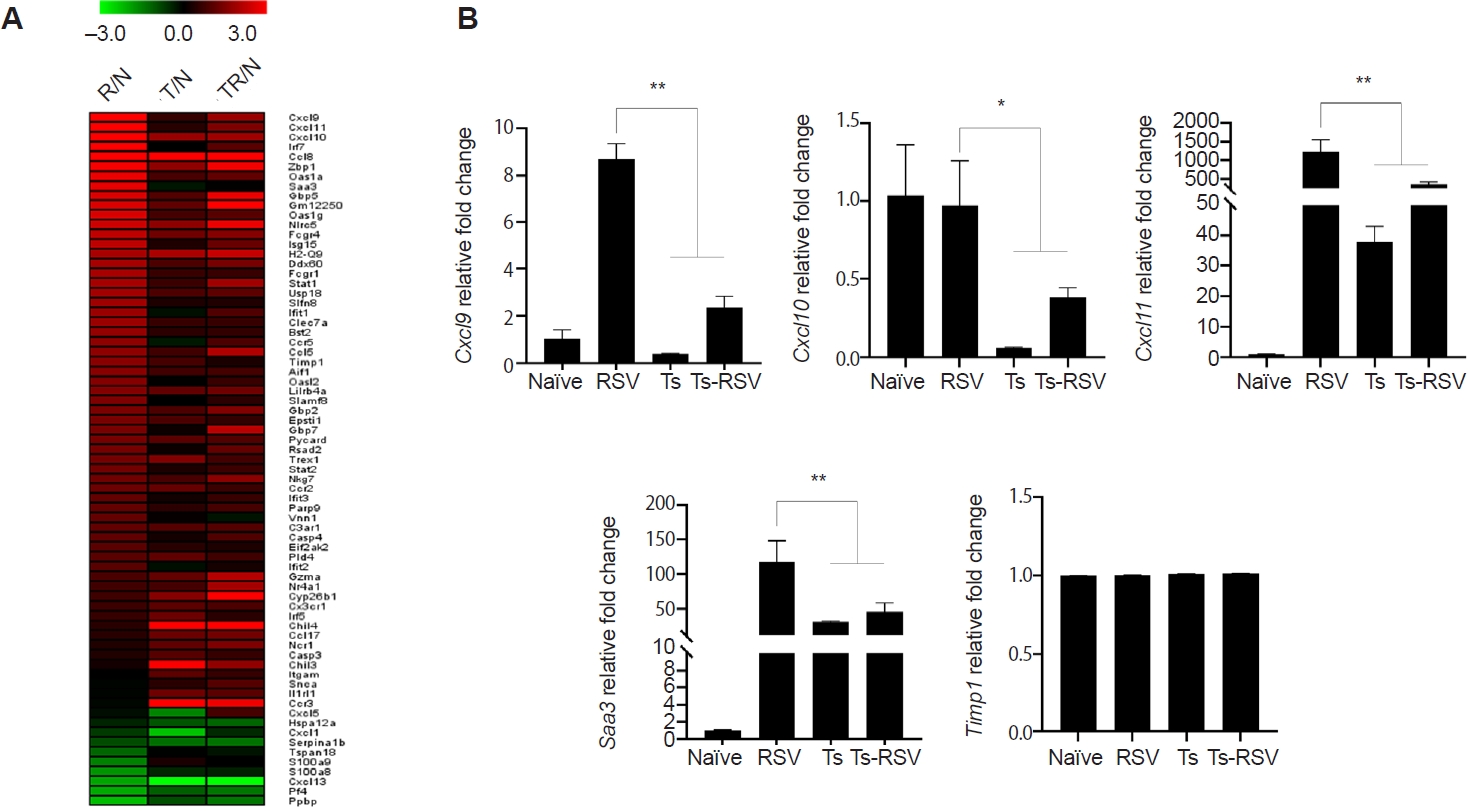

Of the 407 DEGs identified with ≥2-fold changes, 71 genes were classified under either the “inflammatory response” (GO:0006954) or “defense response to virus” (GO:0051607) categories. These 71 DEGs were visualized in a heatmap, illustrating their relative fold-changes compared with naïve controls (

Fig. 4A). To validate the RNA-seq results, qPCR was performed on selected genes previously implicated in RSV-induced inflammation. Specifically, RSV-induced changes to

Cxcl9,

Cxcl10,

Cxcl11,

Saa3, and

Timp1 expressions were evaluated (

Fig. 4B). Consistent with RNA-seq data,

Cxcl9 expression was strongly upregulated in RSV-infected mice but was significantly suppressed in the presence of

T. spiralis. A similar pattern was observed for

Cxcl11,

Cxcl10, and

Saa3, all of which were markedly induced by RSV but attenuated in co-infected mice. In contrast, expression of

Timp1, despite its known roles in inflammation and tissue repair, remained at basal levels across all groups. This observation differed from the RNA-seq heatmap, which suggested a gradual reduction in

Timp1 expression in

T. spiralis-exposed mice. An overview of how

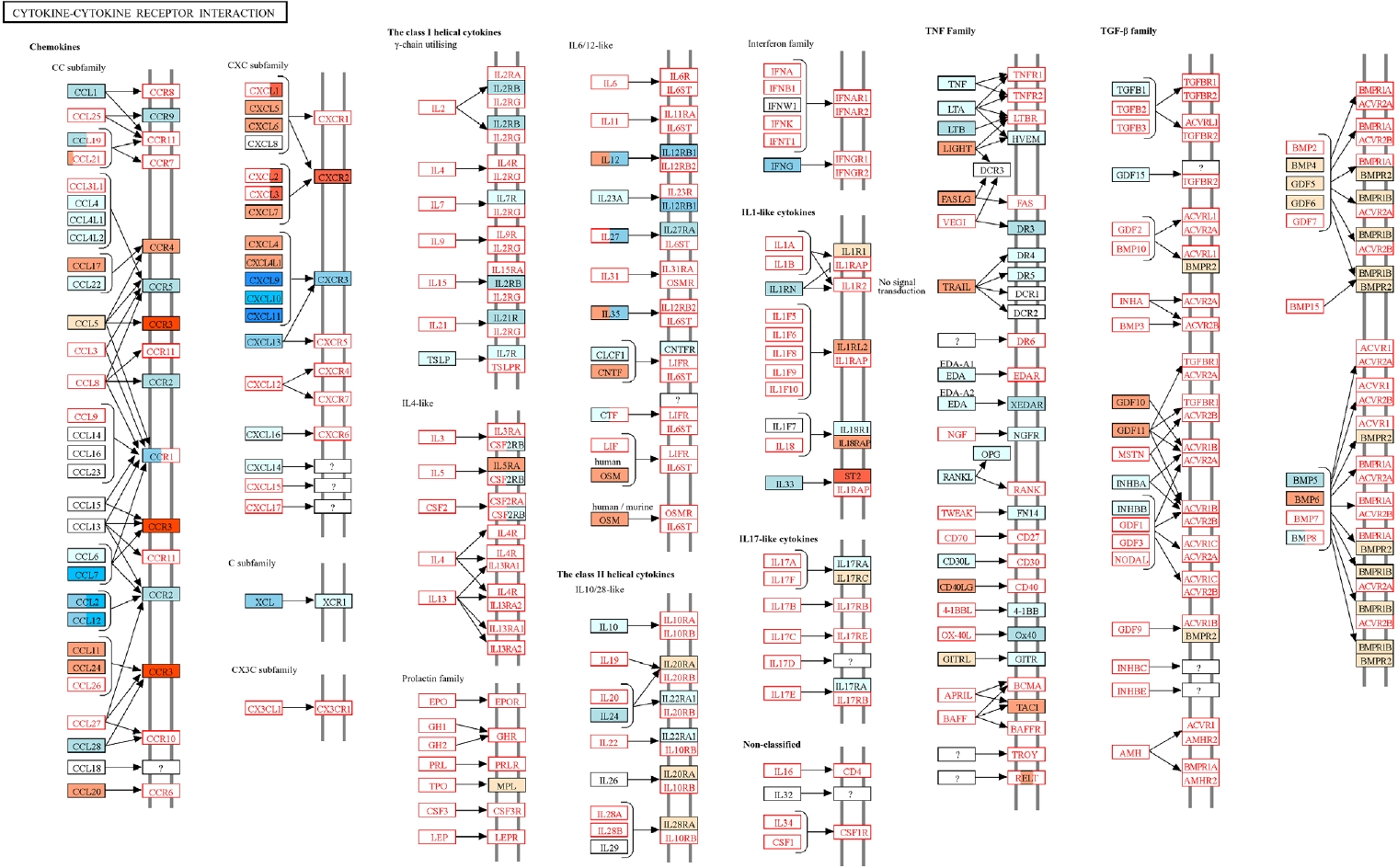

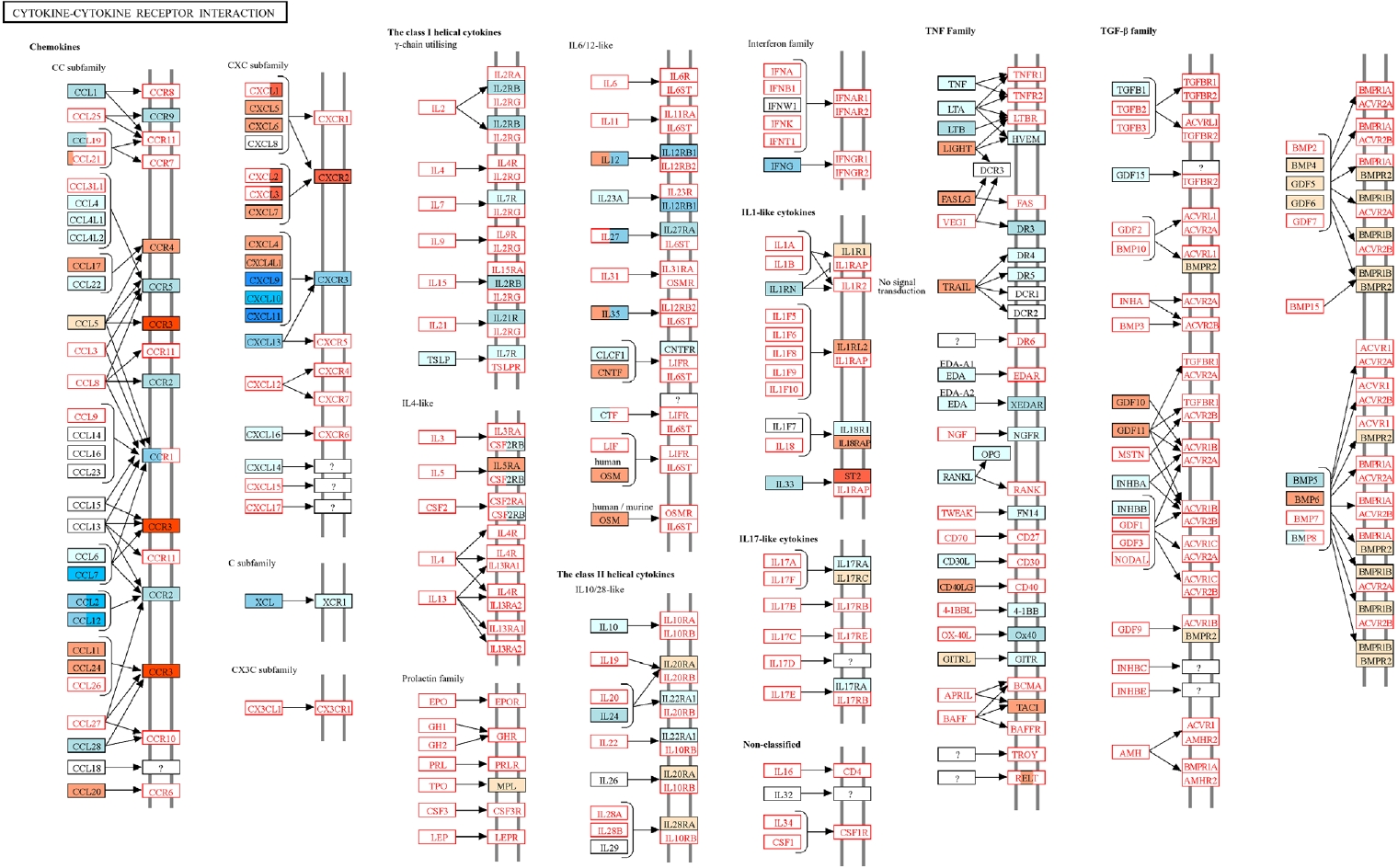

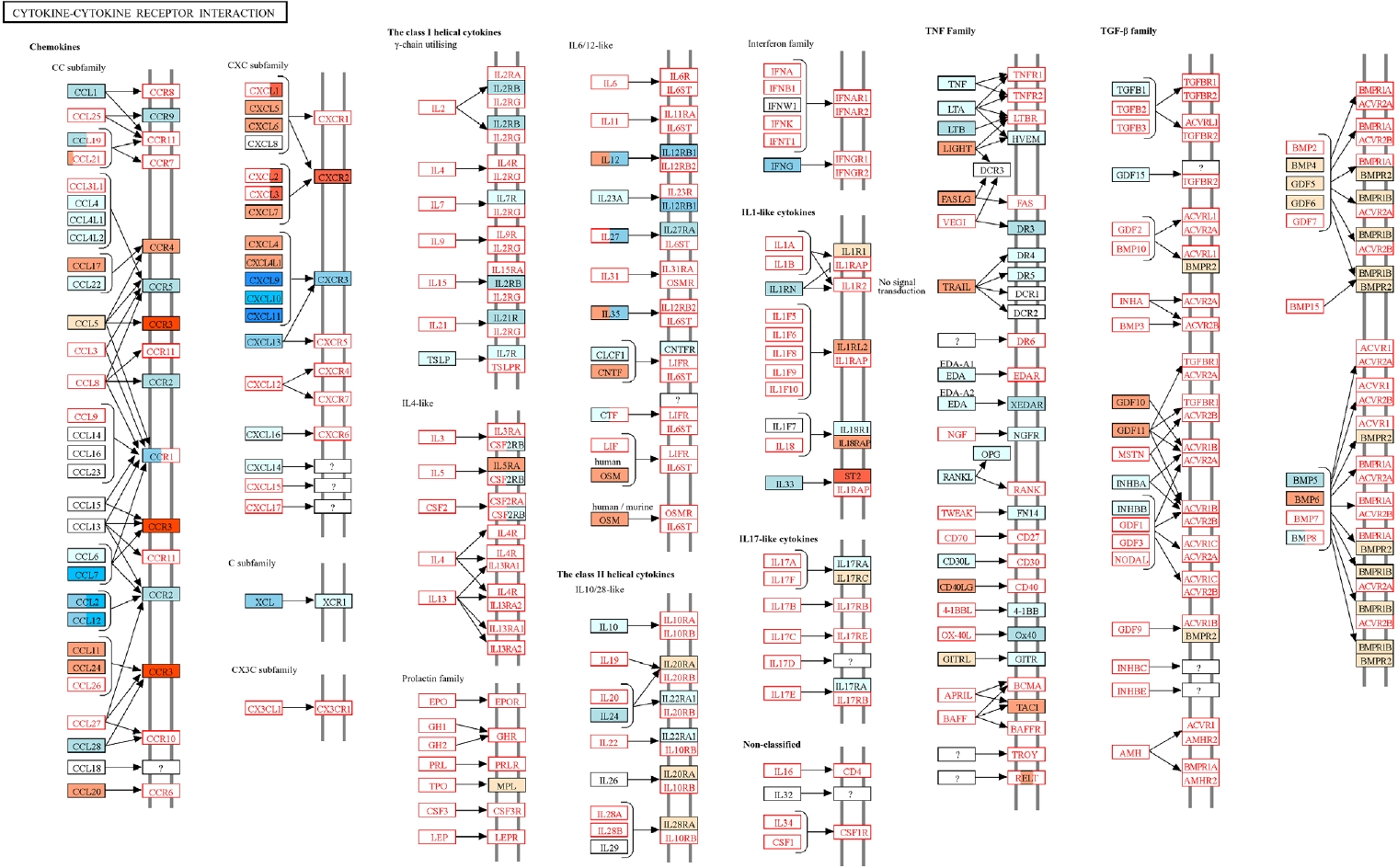

T. spiralis infection modulated RSV-induced inflammatory response was obtained through KEGG pathway analysis (

Fig. 5) [

18]. Genes upregulated and downregulated in the Ts-RSV group relative to RSV alone were color-coded in red and blue, respectively. Consistent with the RNA-seq data, several chemokines such as CXCL9-11, CCL2, and CCL7 were markedly downregulated, indicating attenuated recruitment of monocytes and Th1-associated effector cells. In contrast, receptors including CCR3 and CXCR2 were upregulated, suggesting a shift toward eosinophilic or tissue repair-associated chemotaxis. Cytokines within the TNF family and interferon families, including IFN-γ also exhibited reduced expression, indicating a general attenuation of cytokine-cytokine receptor signaling in the lungs of Ts-RSV mice.

Discussion

Helminth-mediated attenuation of inflammatory responses is a well-documented phenomenon observed across numerous parasitic species, and

T. spiralis is no exception. Multiple studies have highlighted the immunomodulatory properties of

T. spiralis in the context of refractory and chronic immune-mediated disorders [

19]. In the present study, we characterized transcriptomic alterations in mice with pre-existing

T. spiralis infection that were subsequently challenged with RSV. Our findings demonstrate that helminth exposure induces extensive changes in pulmonary gene expression, ultimately contributing to the suppression of virus-induced inflammatory responses.

RSV infection is known to activate multiple signaling pathways, including those involved in immune cell adhesion (e.g.,

Cxcl family chemokines), acute-phase responses mediated by

Saa3, and Toll-like receptor signaling cascades, among others [

20]. Consistent with these reports, transcriptomic profiling of murine lungs in our study revealed significant upregulation of genes associated with chemoattraction and inflammation [

21,

22]. For example, it is well established that the inflammatory cytokine IFN-γ induces the expression of

Cxcl9,

Cxcl10, and

Cxcl11 [

23]. In our previous work, we demonstrated that pre-existing

T. spiralis infection significantly reduced IFN-γ production in the lungs of RSV-infected mice, consistent with the RNA-seq results presented in this study [

14]. Moreover, other studies have reported that IFN-γ–inducible genes can be drastically overexpressed, with fold changes exceeding 10,000 following infection with the RSV A2 strain [

24]. It is well established that helminth infections induce a shift toward Th2-biased immunity, characterized by the activation of Th2 cytokines and eosinophils, which are essential for parasite clearance. In parallel, helminths promote immunoregulatory responses through induction of IL-10, TGF-β, and regulatory T cells, thereby establishing an anti-inflammatory environment [

25]. In agreement with this paradigm, we observed upregulation of genes associated with Th2 immunity in mice with pre-existing

T. spiralis infection. Notably, the expression of

Chil3 and

Chil4 (encoding chitinase-like proteins 3 and 4) was increased, as shown in the heatmap, both of which are implicated in Th2 polarization and the activation of alternatively activated macrophages [

26,

27]. Similar findings have been reported in the lungs of

Nippostrongylus brasiliensis-infected mice, where acute upregulation of

Chil3/

Chil4 expression led to alternatively activated macrophage activation and subsequent attenuation of pulmonary inflammation [

28]. However, certain discrepancies were observed between our findings and those of previous studies regarding the expression of inflammation-associated genes. In our study, inflammation-associated genes were upregulated to a greater extent than previously reported, which is likely attributable to the higher RSV inoculum used—approximately threefold greater than in earlier experiments. Other inconsistencies were also noted. For example, while pre-existing

T. spiralis infection was expected to suppress

Timp1 expression, transcriptome analysis indicated upregulation in RSV-infected mice. In contrast, qPCR validation revealed that

Timp1 expression remained near basal levels across all groups. Such discrepancies are not unexpected, as RNA-seq, despite its robustness, does not always yield results concordant with qPCR or microarray analyses. Indeed, transcriptomic studies have shown that 15%–20% of expressed genes may display non-concordance, either through differential directionality of expression or by the identification of DEGs in 1 platform but not in another [

29].

There are several limitations that must be acknowledged. First, RNA-seq analysis was performed using a single biological sample per experimental group. Consequently, the differential-expression data should be regarded as exploratory rather than inferential, since statistical confidence metrics such as P-values and false discovery rates cannot be fully validated without biological replication. Nevertheless, the observed transcriptomic trends and the enrichment of regulatory pathways were consistent with our histopathological and cytokine findings, lending biological plausibility to the proposed immunomodulatory effects of T. spiralis pre-infection. Future studies including replicate samples and cell-type specific transcriptomic profiling will be important to confirm and refine these mechanistic insights. Another limitation of this study is that cytokine concentrations and immune-cell subsets were not directly measured. Although the transcriptomic data indicated activation of Th2-associated and regulatory pathways, these findings were inferred from gene-expression profiles rather than confirmed by functional assays. Future studies incorporating cytokine quantification and immunophenotyping of regulatory T cells and alternatively activated macrophages will be important to validate the transcriptional predictions and clarify the cellular mechanisms underlying T. spiralis–mediated immunomodulation.

While our findings demonstrate that helminth-mediated immunomodulation can be elicited by

T. spiralis and that such responses confer protection against RSV infection, several key questions remain unresolved. First, our study did not determine whether the protective effects and associated gene expression changes were driven primarily by live infection or by specific parasite-derived molecules. Notably, randomized clinical trials in humans have shown that administration of

Trichuris suis ova did not significantly alleviate allergic rhinitis [

25], suggesting that either persistent infection or parasite-derived secretory products may be necessary to induce protection. Second, the infection dose required to achieve immunomodulation while minimizing host pathology remains unclear. For example, protection against airway hyperresponsiveness in Wistar rats was reported following infection with 5,000

Strongyloides venezuelensis L3 larvae [

30]. By contrast, inoculation with 5,000

T. spiralis muscle larvae is not feasible, particularly in humans, who are highly susceptible to

T. spiralis infection; ingestion of even a small number of larvae in contaminated meat poses a risk for trichinosis [

31].

T. spiralis-derived excretory-secretory (ES) antigens have emerged as more realistic therapeutic candidates because direct application of live

T. spiralis is not feasible due to safety concerns. Several

T. spiralis components have demonstrated anti-inflammatory properties in animal models. For example,

T. spiralis cystatin regulates macrophage polarization toward an anti-inflammatory phenotype, thereby ameliorating sepsis-induced inflammation and improving survival in mice [

32]. Likewise,

T. spiralis chitinase markedly reduces allergic airway inflammation by suppressing Th2-associated immune responses [

33]. Because individual

T. spiralis antigen likely act through distinct mechanisms and some may even exacerbate inflammation [

34], careful selection and rigorous preclinical evaluation of candidate molecules will be essential for their safe therapeutic application. Finally, the duration of infection may critically influence the extent of helminth-mediated protection. In our study, RSV infection was introduced 12 days post-

T. spiralis infection, based on prior reports indicating that this is the last time point at which migratory larvae can still be detected in the lungs [

35]. However, we did not investigate whether encysted muscle-stage larvae are capable of modulating immune responses in distal organs such as the lungs. Collectively, these lingering questions highlight the need for future studies to determine whether protection is mediated by live infection or parasite-derived products, to establish safe and effective dosing strategies, and to define the temporal window during which

T. spiralis exerts its immunomodulatory effects.

In conclusion, this study demonstrates that pre-existing T. spiralis infection induces transcriptomic changes in the lungs that attenuate RSV-induced pulmonary inflammation and tissue damage. Although the precise mechanisms underlying this protective effect remain to be elucidated, our findings suggest that T. spiralis possesses therapeutic potential in modulating pathogen-induced inflammatory diseases. Future studies aimed at identifying the specific components of T. spiralis responsible for these anti-inflammatory effects will not only advance our understanding of helminth-derived immunomodulation but may also facilitate the development of novel prophylactic or therapeutic strategies for managing inflammatory disorders.

Notes

-

Author contributions

Conceptualization: Chu KB, Quan FS. Funding acquisition: Chu KB. Investigation: Chu KB. Project administration: Quan FS. Supervision: Quan FS. Visualization: Chu KB. Writing – original draft: Chu KB. Writing – review & editing: Chu KB, Quan FS.

-

Conflict of interest

Fu-Shi Quan serves as an editor of Parasites, Hosts and Diseases but had no involvement in the decision to publish this article. No other potential conflicts of interest relevant to this study were reported.

-

Funding

This work was supported by the 2024 Inje University research grant.

Fig. 1.Anti-inflammatory effects of Trichinella spiralis (Ts) infection in mice. The effect of pre-existing Ts infection on respiratory syncytial virus (RSV)-induced inflammation in mice (n=5 per group) were evaluated via lung tissue staining and plaque assay. Hematoxylin and eosin-stained lung tissue sections were visualized under a microscope and images were acquired under 100× magnification (A). RSV titers in the lung homogenates of mice were quantified by performing plaque assays using confluent monolayers of HEp-2 cells (B). Data are presented as mean±SD (*P<0.05).

Fig. 2.Transcriptome profiling of lung tissues from infected mice. A Venn diagram depicting the concordance of differentially expressed genes between R/N (respiratory syncytial virus vs. naïve), T/N (T. spiralis vs. naïve), and TR/N (co-infection vs. naïve) groups (A). Enriched genes classified under the 3 principal Gene Ontology domains are shown, with downregulated genes indicated in purple and upregulated genes in yellow (B). BP, Biological Process; CC, Cellular Component; MF, Molecular Function.

Fig. 3.Gene Ontology (GO) analysis of lung transcriptomes from respiratory syncytial virus–infected and co-infected mice. Enriched GO terms were identified from RNA sequencing data, and the relative proportion of genes associated with each GO term is shown as a percentage of the total significant categories. Differentially expressed gene categories and their relative proportions were analyzed for respiratory syncytial virus vs. naïve (A) and co-infection vs. naïve (B).

Fig. 4.Heatmap of genes upregulated and downregulated by Trichinella spiralis (Ts) infection in the lungs. Differentially expressed genes categorized under GO:0006954 and GO:0051607 were compiled and a heatmap was drawn using the MeV software (A). Expression of genes whose association with respiratory syncytial virus (RSV)-induced inflammation was validated through quantitative real-time PCR from the right lung lobes of mice (n=5 per group) (B). All gene expression values were normalized to beta-actin (Actb). Data are presented as mean±SD (*P<0.05, **P<0.01). R/N, RSV vs. naïve; T/N, T. spiralis vs. naïve; TR/N, co-infection vs. naïve.

Fig. 5.Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway analysis of cytokine-cytokine receptor interactions in the lungs of

Trichinella spiralis (Ts) plus respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) mice. Differentially expressed genes identified from RNA sequencing data were mapped onto the KEGG pathway

mmu04060 using KEGG Mapper. Genes upregulated or downregulated in the Ts-RSV group relative to RSV control group are indicated in red and blue, respectively. Pathway map modified from KEGG with permission from Kanehisa Laboratories [

18].

Table 1.Quantitative real-time PCR primers used in this study

Table 1.

|

Gene |

Primer sequence (5’ – 3’) |

GenBank ID |

|

Cxcl9

|

F: CCGAGGCACGATCCACTACA |

NM_008599.4 |

|

R: CGAGTCCGGATCTAGGCAGGT |

|

Cxcl10

|

F: ATCATCCCTGCGAGCCTATCCT |

NM_021274.2 |

|

R: GACCTTTTTTGGCTAAACGCTTTC |

|

Cxcl11

|

F: CCGAGTAACGGCTGCGACAAAG |

NM_019494.1 |

|

R: CCTGCATTATGAGGCGAGCTTG |

|

Saa3

|

F: CGCAGCACGAGCAGGAT |

NM_011315.3 |

|

R: CCAGGATCAAGATGCAAAGAATG |

|

Timp1

|

F: GTGGGAAATGCCGCAGAT |

NM_001044384.1 |

|

R: GGGCATATCCACAGAGGCTTT |

|

Actb

|

F: CCACCATGTACCCAGGCATT |

NM_007393.5 |

|

R: CGGACTCATCGTACTCCTGC |

References

- 1. Ryan SM, Eichenberger RM, Ruscher R, Giacomin PR, Loukas A. Harnessing helminth-driven immunoregulation in the search for novel therapeutic modalities. PLoS Pathog 2020;16:e1008508. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.ppat.1008508

- 2. Chen J, Gong Y, Chen Q, Li S, Zhou Y. Global burden of soil-transmitted helminth infections, 1990-2021. Infect Dis Poverty 2024;13:77. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40249-024-01238-9

- 3. Parker W, Ollerton J. Evolutionary biology and anthropology suggest biome reconstitution as a necessary approach toward dealing with immune disorders. Evol Med Public Health 2013;2013:89-103. https://doi.org/10.1093/emph/eot008

- 4. Gerrard JW, Geddes CA, Reggin PL, Gerrard CD, Horne S. Serum IgE levels in white and metis communities in Saskatchewan. Ann Allergy 1976;37:91-100.

- 5. Evans H, Mitre E. Worms as therapeutic agents for allergy and asthma: understanding why benefits in animal studies have not translated into clinical success. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2015;135:343-53. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaci.2014.07.007

- 6. Correale J, Farez M. Association between parasite infection and immune responses in multiple sclerosis. Ann Neurol 2007;61:97-108. https://doi.org/10.1002/ana.21067

- 7. Broadhurst MJ, Leung JM, Kashyap V, et al. IL-22+ CD4+ T cells are associated with therapeutic trichuris trichiura infection in an ulcerative colitis patient. Sci Transl Med 2010;2:60ra88. https://doi.org/10.1126/scitranslmed.3001500

- 8. Tong M, Yang X, Qiao Y, et al. Serine protease inhibitor from the muscle larval Trichinella spiralis ameliorates non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in mice via anti-inflammatory properties and gut-liver crosstalk. Biomed Pharmacother 2024;172:116223. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopha.2024.116223

- 9. Jo YR, Park HT, Yu HS, Kong HH. Trichinella infection ameliorated vincristine-induced neuroinflammation in mice. Korean J Parasitol 2022;60:247-54. https://doi.org/10.3347/kjp.2022.60.4.247

- 10. Li H, Qiu D, Yang H, et al. Therapeutic efficacy of excretory-secretory products of Trichinella spiralis adult worms on sepsis-induced acute lung injury in a mouse model. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 2021;11:653843. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcimb.2021.653843

- 11. Long SR, Shang WX, Jiang M, et al. Preexisting Trichinella spiralis infection attenuates the severity of Pseudomonas aeruginosa-induced pneumonia. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2022;16:e0010395. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pntd.0010395

- 12. Cao Z, Wang J, Liu X, et al. Helminth alleviates COVID-19-related cytokine storm in an IL-9-dependent way. mBio 2024;15:e0090524. https://doi.org/10.1128/mbio.00905-24

- 13. Elmehy DA, Abdelhai DI, Elkholy RA, et al. Immunoprotective inference of experimental chronic Trichinella spiralis infection on house dust mites induced allergic airway remodeling. Acta Trop 2021;220:105934. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actatropica.2021.105934

- 14. Chu KB, Lee HA, Kang HJ, Moon EK, Quan FS. Preliminary Trichinella spiralis infection ameliorates subsequent RSV infection-induced inflammatory response. Cells 2020;9:1314. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells9051314

- 15. Chu KB, Kim SS, Lee SH, et al. Immune correlates of resistance to Trichinella spiralis reinfection in mice. Korean J Parasitol 2016;54:637-43. https://doi.org/10.3347/kjp.2016.54.5.637

- 16. Chu KB, Lee DH, Kang HJ, Quan FS. The resistance against Trichinella spiralis infection induced by primary infection with respiratory syncytial virus. Parasitology 2019;146:634-42. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0031182018001889

- 17. Robinson MD, McCarthy DJ, Smyth GK. edgeR: a Bioconductor package for differential expression analysis of digital gene expression data. Bioinformatics 2010;26:139-40. https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btp616

- 18. Ogata H, Goto S, Sato K, et al. KEGG: Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes. Nucleic Acids Res 1999;27:29-34. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/27.1.29

- 19. Cho M, Yu HS. Therapeutic potentials of Trichinella spiralis in immune disorders: from allergy to autoimmunity. Parasites Hosts Dis 2025;63:123-34. https://doi.org/10.3347/PHD.24086

- 20. Marzec J, Cho HY, High M, et al. Toll-like receptor 4-mediated respiratory syncytial virus disease and lung transcriptomics in differentially susceptible inbred mouse strains. Physiol Genomics 2019;51:630-43. https://doi.org/10.1152/physiolgenomics.00101.2019

- 21. Janssen R, Pennings J, Hodemaekers H, et al. Host transcription profiles upon primary respiratory syncytial virus infection. J Virol 2007;81:5958-67. https://doi.org/10.1128/JVI.02220-06

- 22. Schuurhof A, Bont L, Pennings JL, et al. Gene expression differences in lungs of mice during secondary immune responses to respiratory syncytial virus infection. J Virol 2010;84:9584-94. https://doi.org/10.1128/JVI.00302-10

- 23. Han JH, Suh CH, Jung JY, et al. Elevated circulating levels of the interferon-γ-induced chemokines are associated with disease activity and cutaneous manifestations in adult-onset Still's disease. Sci Rep 2017;7:46652. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep46652

- 24. Feng Q, Feng Z, Yang B, et al. Metatranscriptome reveals specific immune and microbial signatures of respiratory syncytial virus infection in children. Microbiol Spectr 2023;11:e0410722. https://doi.org/10.1128/spectrum.04107-22

- 25. Helmby H. Human helminth therapy to treat inflammatory disorders: where do we stand? BMC Immunol 2015;16:12. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12865-015-0074-3

- 26. Kang Q, Li L, Pang Y, Zhu W, Meng L. An update on Ym1 and its immunoregulatory role in diseases. Front Immunol 2022;13:891220. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2022.891220

- 27. Nutman TB. Looking beyond the induction of Th2 responses to explain immunomodulation by helminths. Parasite Immunol 2015;37:304-13. https://doi.org/10.1111/pim.12194

- 28. Reece JJ, Siracusa MC, Scott AL. Innate immune responses to lung-stage helminth infection induce alternatively activated alveolar macrophages. Infect Immun 2006;74:4970-81. https://doi.org/10.1128/IAI.00687-06

- 29. Coenye T. Do results obtained with RNA-sequencing require independent verification? Biofilm 2021;3:100043. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bioflm.2021.100043

- 30. Negrão-Corrêa D, Silveira MR, Borges CM, Souza DG, Teixeira MM. Changes in pulmonary function and parasite burden in rats infected with Strongyloides venezuelensis concomitant with induction of allergic airway inflammation. Infect Immun 2003;71:2607-14. https://doi.org/10.1128/IAI.71.5.2607-2614.2003

- 31. Teunis PF, Koningstein M, Takumi K, van der Giessen JW. Human beings are highly susceptible to low doses of Trichinella spp. Epidemiol Infect 2012;140:210-8. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0950268811000380

- 32. Li H, Qiu D, Yuan Y, et al. Trichinella spiralis cystatin alleviates polymicrobial sepsis through activating regulatory macrophages. Int Immunopharmacol 2022;109:108907. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intimp.2022.108907

- 33. Xu J, Yao Y, Zhuang Q, et al. Characterization of a chitinase from Trichinella spiralis and its immunomodulatory effects on allergic airway inflammation in mice. Parasit Vectors 2025;18:6. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13071-024-06656-0

- 34. Wang R, Zhang Y, Li Z, et al. Effects of Trichinella spiralis and its serine protease inhibitors on intestinal mucosal barrier function. Vet Res 2025;56:7. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13567-024-01446-z

- 35. Harley JP, Gallicchio V. Trichinella spiralis: migration of larvae in the rat. Exp Parasitol 1971;30:11-21. https://doi.org/10.1016/0014-4894(71)90064-6