Abstract

Vertical transfer of maternal antibodies can provide passive protection to offspring against specific pathogens. In this study, we detected antibodies in the sera of uninfected offspring born to chronically Trichinella spiralis-infected female mice. Immunoblotting consistently revealed a distinct band at ~38 kDa in both T. spiralis excretory-secretory products and total somatic extracts. This band was identified by MALDI-TOF/TOF mass spectrometry as a cystatin-like protein of T. spiralis (Ts-CLP). Structural modeling and domain analysis indicated a typical cystatin-like fold comprising a central α-helix and an antiparallel β-sheet core. To confirm antigen identity, recombinant Ts-CLP protein was expressed and used to generate a polyclonal anti-recombinant Ts-CLP protein antibody. This antibody specifically recognized a ~38 kDa band in T. spiralis excretory-secretory products and total somatic extracts, consistent with that detected by offspring sera. Collectively, these findings demonstrate that maternal antibodies specific to Ts-CLP are vertically transferred and detectable in uninfected offspring. Although the functional significance remains to be determined, this observation provides a basis for future studies on passive immunity and host-parasite interactions.

-

Key words: Cystatin-like protein, maternal antibodiesm, Trichinella spiralis, vertical transfer

Trichinella spiralis is a parasitic nematode that employs various immunoevasive strategies to establish chronic infection within its host. Among these strategies, the secretion of immunomodulatory proteins as part of the parasite’s excretory-secretory products (ESPs) plays a critical role in modulating host immune responses[

1-

4]. One such molecule, a cystatin protein, has been reported to suppress host cysteine protease activity, potentially interfering with antigen processing and presentation, as well as inflammatory signaling [

5-

9]. However, little is known about host antibody responses to this molecule, or whether such responses can be vertically transmitted to offspring.

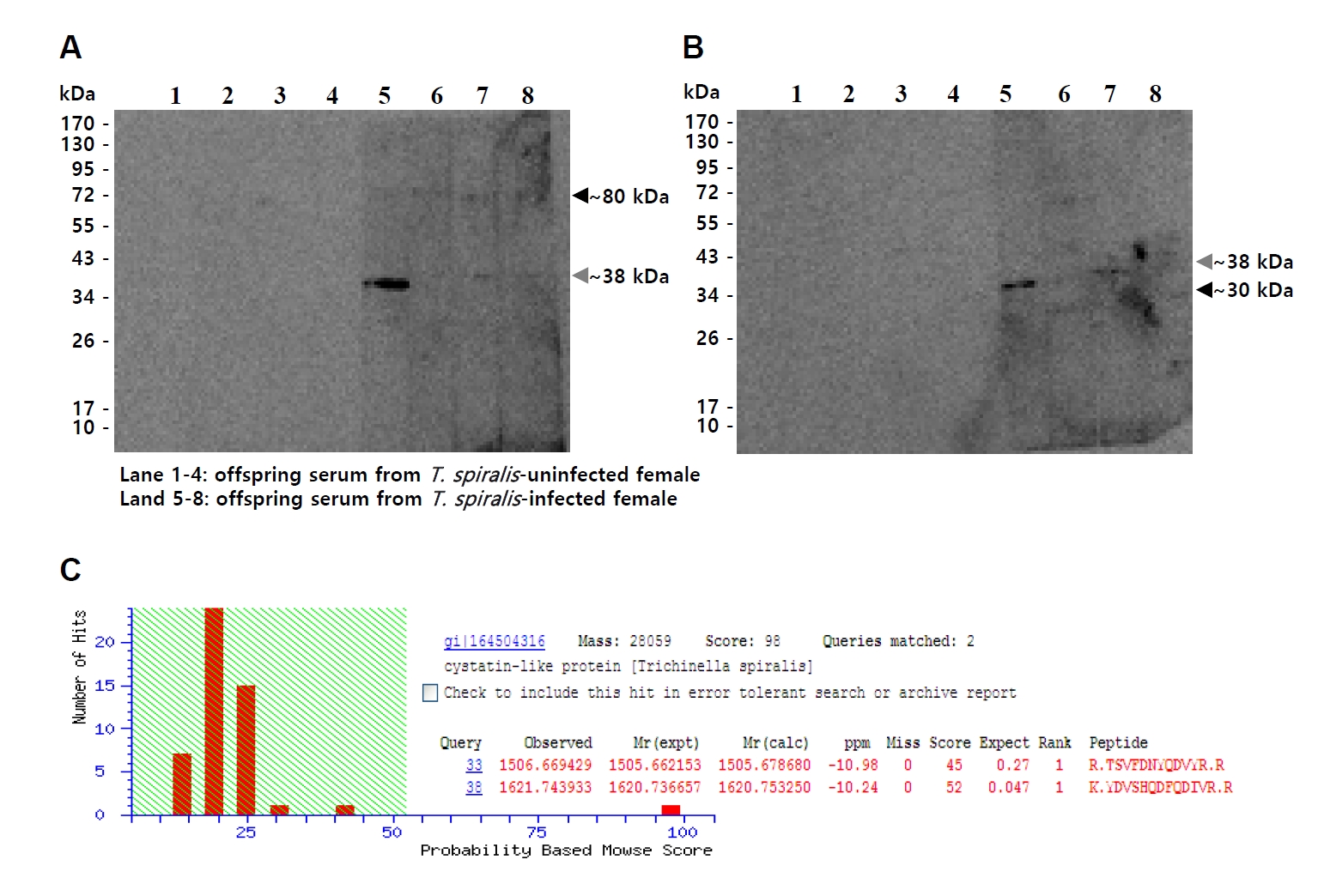

In the present study, we investigated the possibility of maternal antibody transfer in a murine model chronically infected with

T. spiralis, and identified a parasite-derived antigen recognized by these antibodies in uninfected offspring delivered by infected female mice. Female C57BL/6 mice (6 weeks old) were orally infected with 250

T. spiralis muscle larvae. All animal experiments were conducted in accordance with institutional guidelines and were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Pusan National University (No. PNU-2013-0293). After 4 weeks of infection, the female mice were mated with uninfected males to produce offspring. To confirm that the offspring were uninfected, muscle tissue samples were examined by direct microscopic observation of compressed tissue preparations, and no parasites were detected. Sera were collected from the offspring at 5 weeks of age and used as primary antibody sources in Western blot analyses against

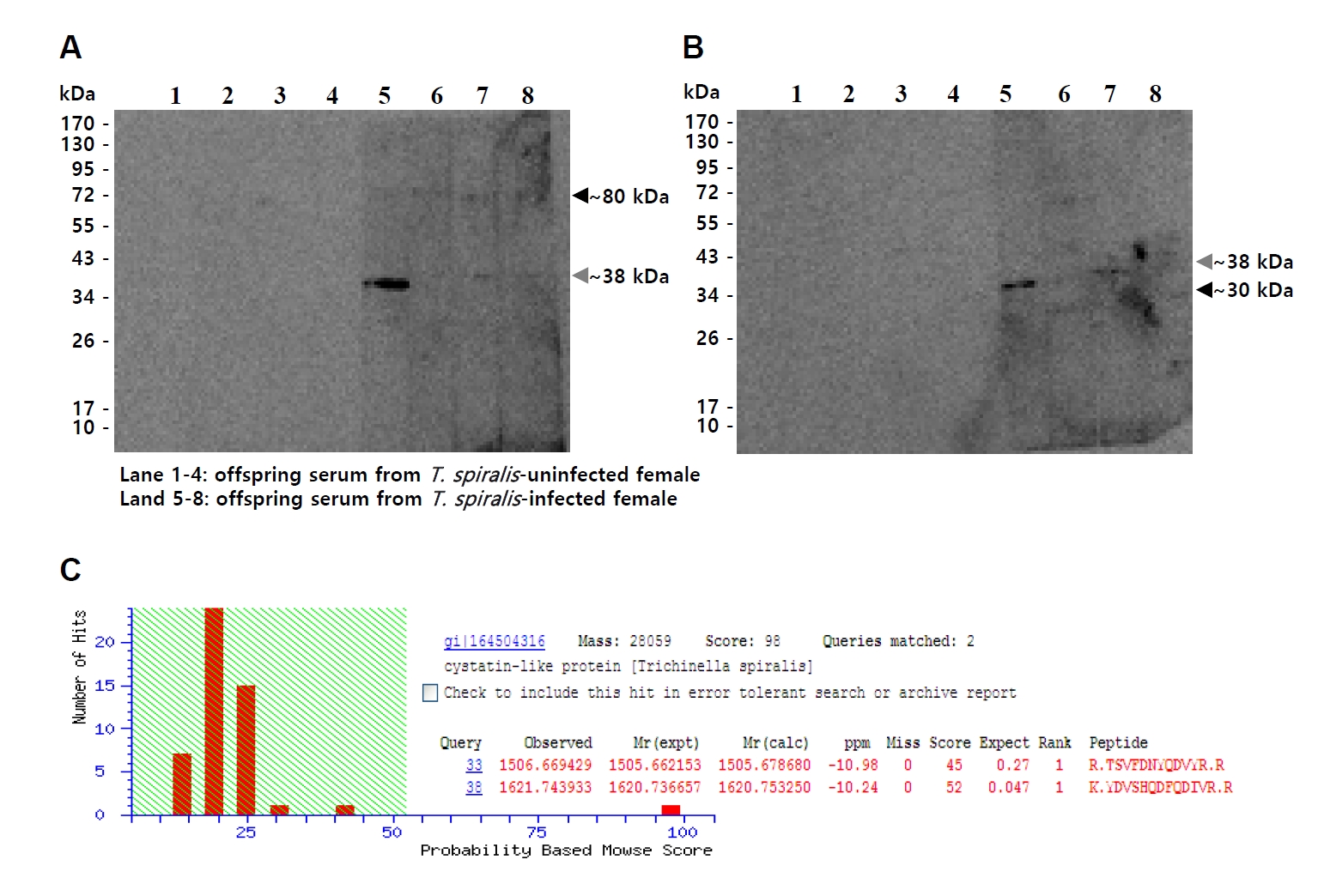

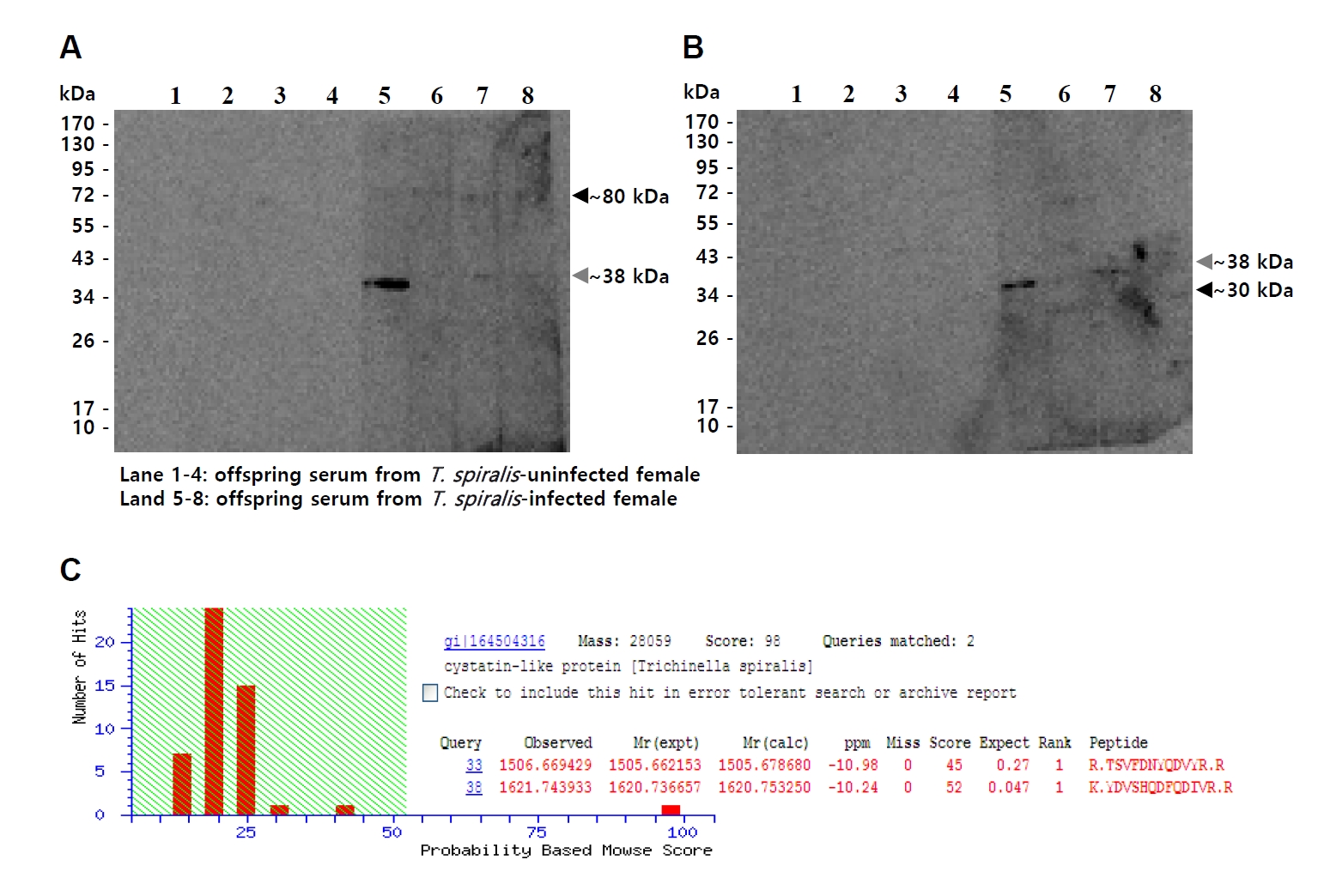

T. spiralis ESPs and total somatic extracts (TSEs). Immunoblotting consistently revealed a band migrating at approximately 38 kDa (gray arrowhead) in both ESPs and TSEs. In addition, bands at around 80 kDa in ESPs (black arrowhead) and 30 kDa in TSEs (black arrowhead) were also observed. (

Fig. 1A,

B). To identify the common band at ~38 kDa, this band was excised and subjected to MALDI-TOF/TOF mass spectrometry, which identified it as a cystatin-like protein of

T. spiralis (Ts-CLP) (

Fig. 1C).

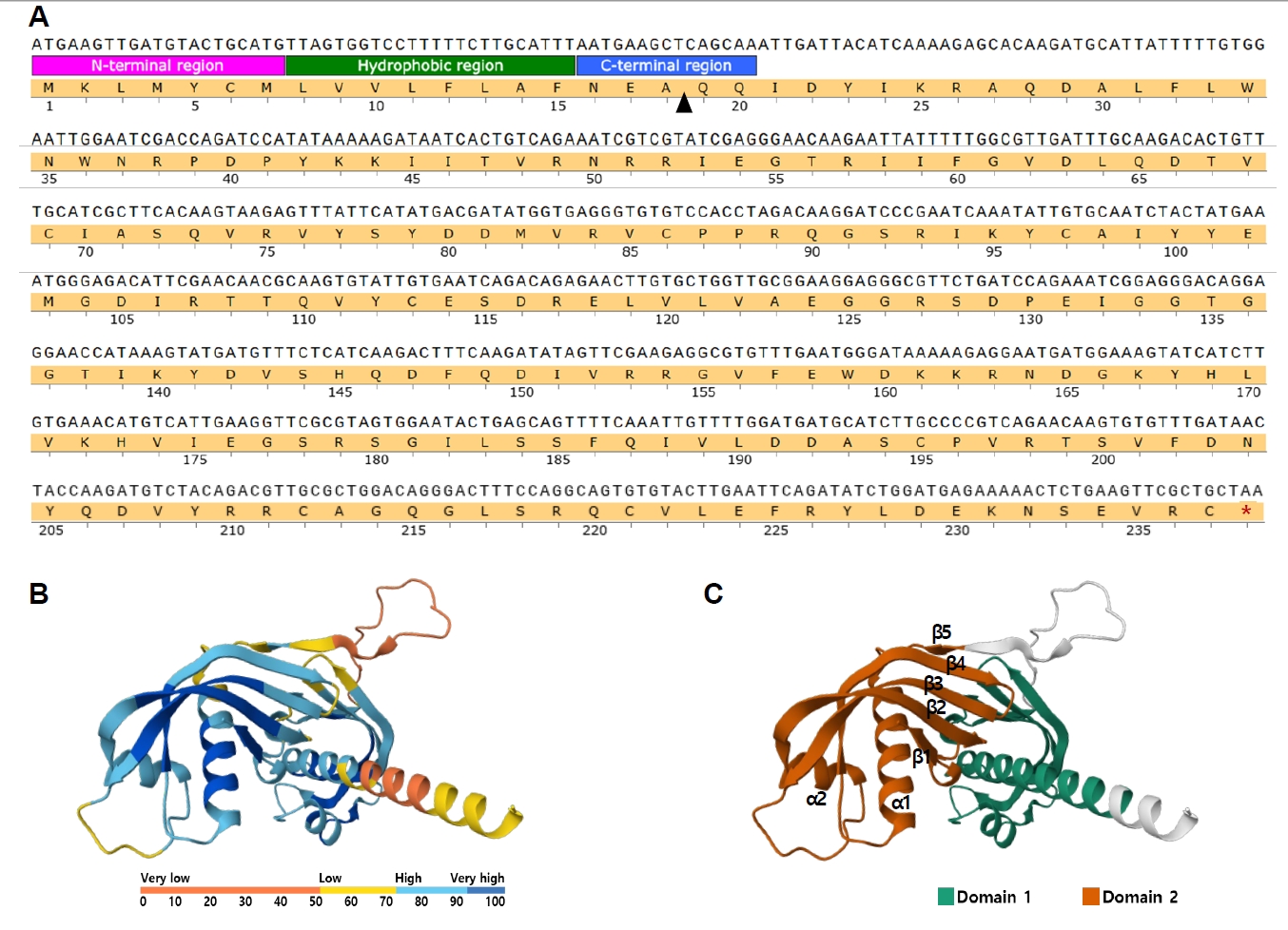

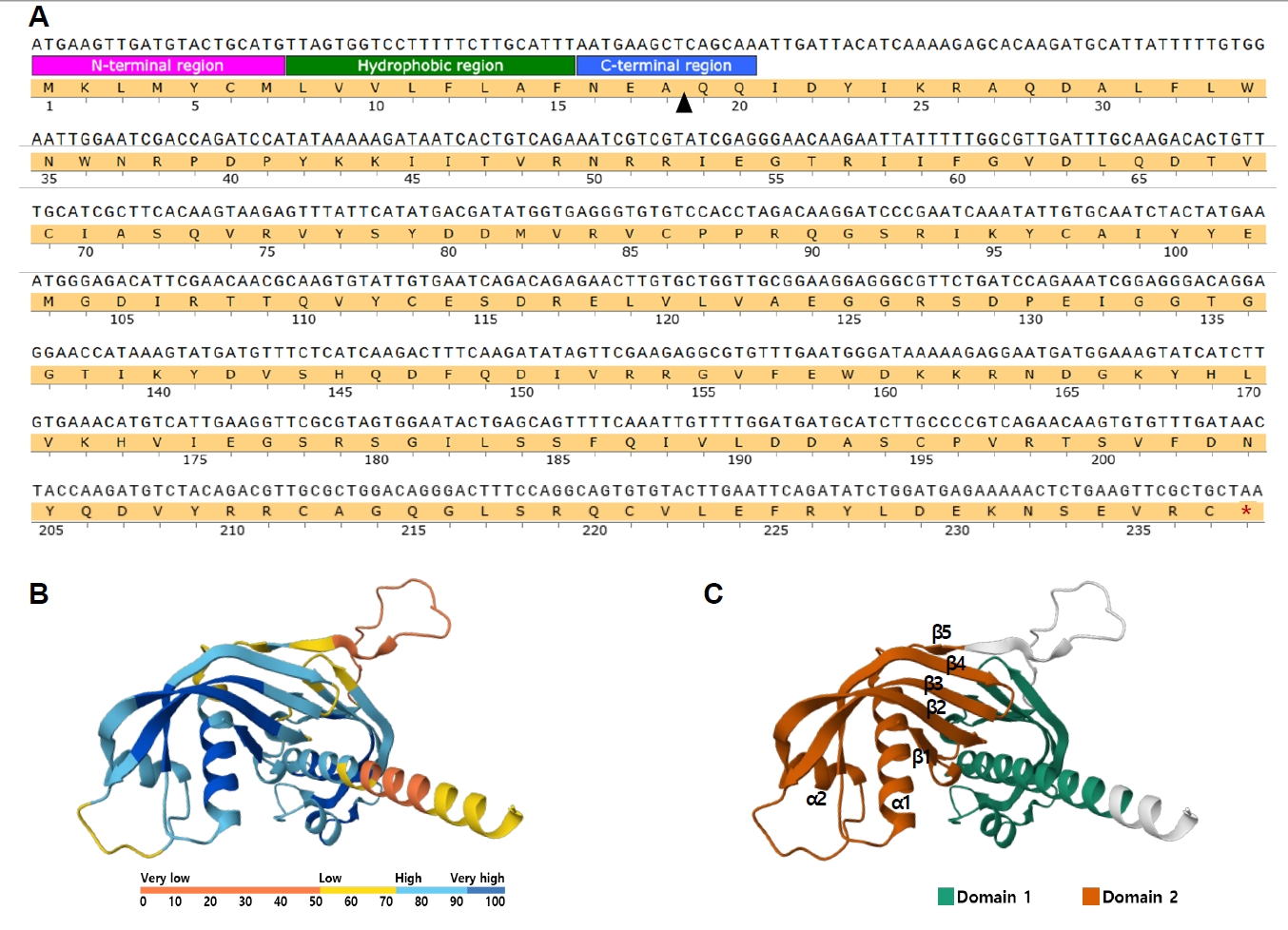

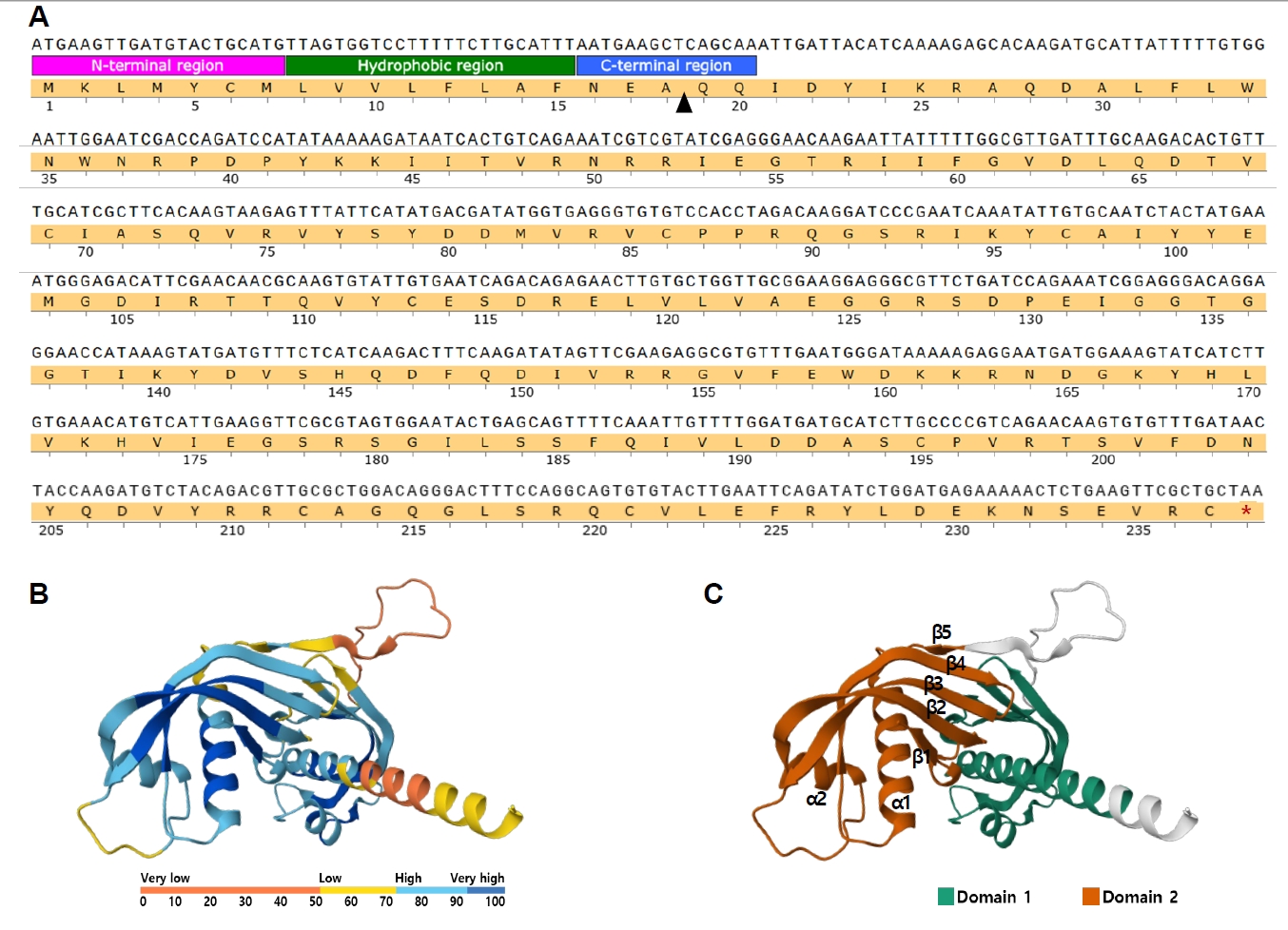

Biotechnology Information for cystatin-like protein (accession No. ABY59464.1; previously GI: 164504316), consistent with the GI number identified in the MALDI-TOF/TOF analysis. The nucleotide sequence comprised 714 bp, encoding an amino acid sequence of 237 residues, with a predicted molecular weight of 27.5 kDa. Signal peptide analysis using InterPro (

https://www.ebi.ac.uk/interpro) predicted a 20-residue signal peptide at the N-terminus, with residues 1–7 corresponding to the N-terminal signal region, residues 8–15 forming a hydrophobic core, and residues 16–20 representing the C-terminal signal peptide region (

Fig. 2A). In addition, the amino acid sequence of Ts-CLP was analyzed using the AlphaFold Protein Structure Database (AFDB) (

https://alphafold.ebi.ac.uk). The predicted model was further segmented into structural domains using the Encyclopedia of Domains, which defines consensus domain boundaries across AFDB entries by integrating multiple structure-based methods [

10]. The AFDB model reproduced the characteristic cystatin-like fold, in which a central α-helix is packed against a 5-stranded antiparallel β-sheet, consistent with previously described cystatin family structures [

11-

13]. The model displayed an average predicted Local Distance Difference Test of 75.12, indicating generally reliable prediction quality (

Fig. 2B). The Encyclopedia of Domains analysis identified 2 structural domains comprising 106 and 98 residues, respectively, while the remaining 33 residues were not assigned to either domain and correspond mainly to terminal and linker regions. Domain 1 (residues 9–114) exhibited an α–β–β–α topology with a central α-helix and short β-strands. Domain 2 (residues 140–237) displayed a β–α–β–β–α–β–β arrangement, in which 5 β-strands assembled into an antiparallel β-sheet core interleaved with 2 α-helices. This organization corresponds to the canonical cystatin architecture described above (

Fig. 2C).

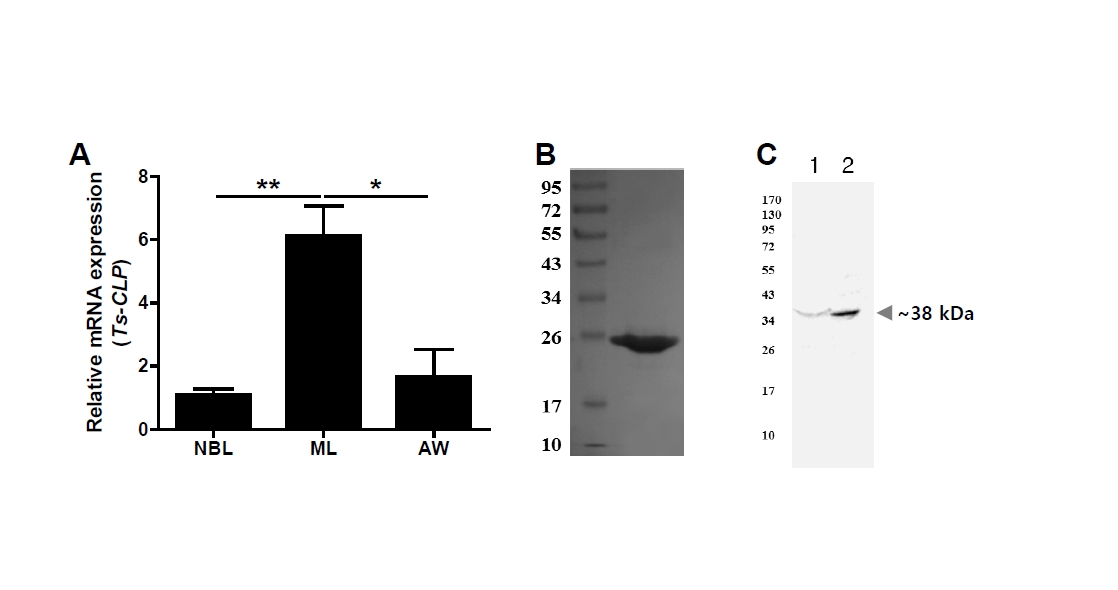

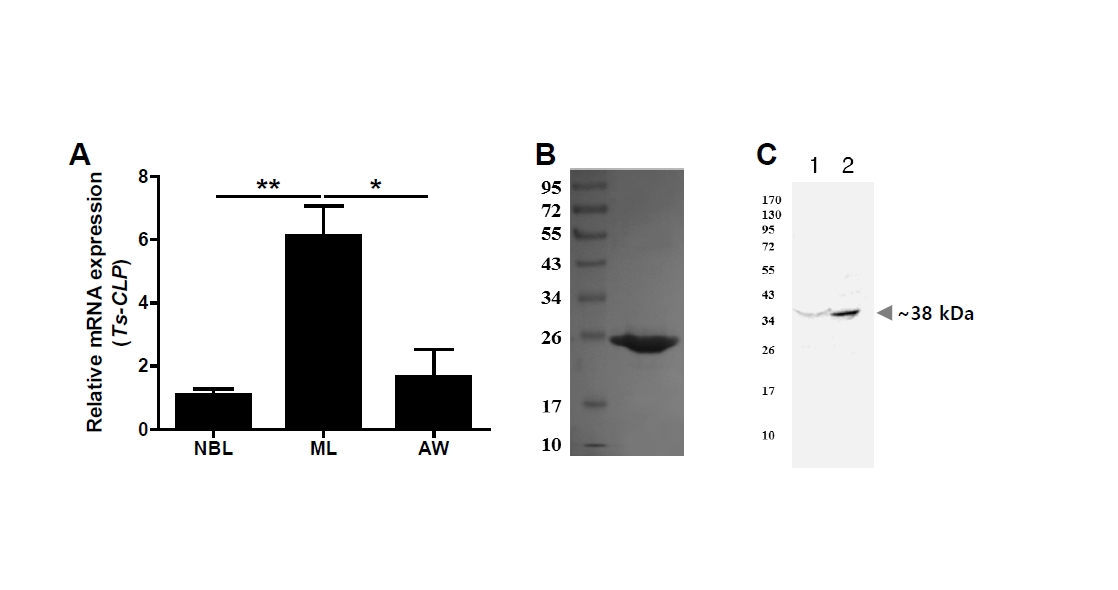

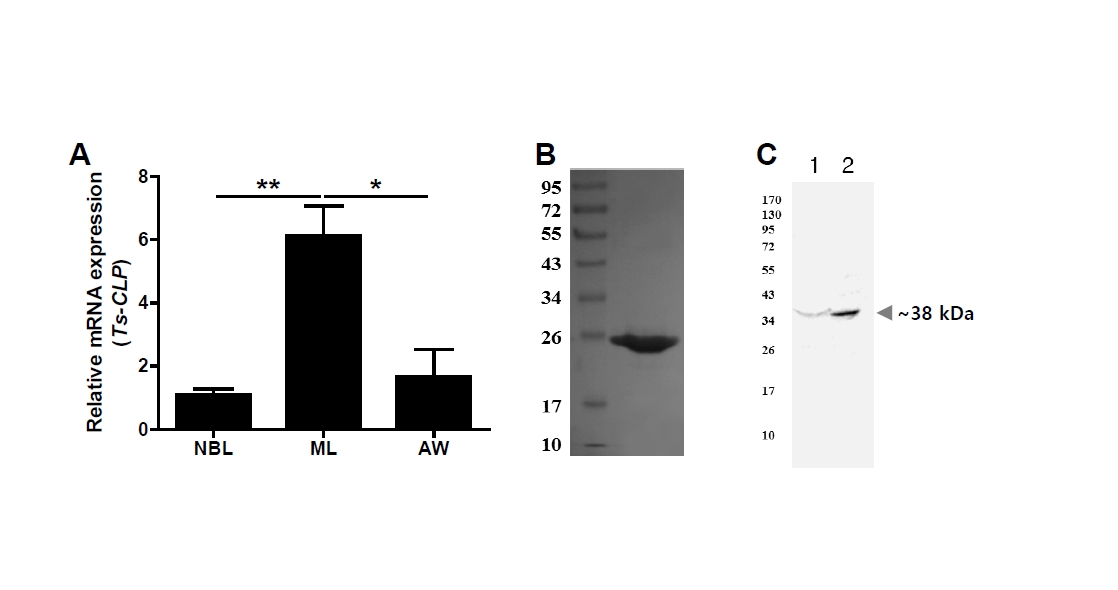

Having established its structural characteristics, we next examined the developmental gene expression of Ts-CLP. Total RNA was extracted from newborn larvae, muscle larvae, and adult worms of

T. spiralis, followed by RT-PCR analysis. Newborn larvae were obtained from adult worm delivery, muscle larvae were collected from infected muscle tissue, and adult worms were recovered from the intestines of infected mice. For each preparation, multiple worms were pooled, and each biological replicate (

n=3) represented an independently prepared pool of parasites obtained from separate infected mice. The Ts-CLP transcript was detected at all life stages, with the highest expression in muscle larvae. This pattern indicates a constitutive expression with stage-specific enhancement, suggesting that Ts-CLP may be particularly important for establishing chronic infection within host tissue (

Fig. 3A). To further validate the identity of the antigen recognized by offspring sera, the Ts-CLP gene was amplified from

T. spiralis cDNA, cloned into the pTNT vector (Promega), and expressed ex vivo using TNT T7 Quick Coupled Transcription/Translation System (Promega). The recombinant Ts-CLP protein (rTs-CLP) was separated on a 10% SDS-PAGE gel and visualized by Coomassie blue staining solution (

Fig. 3B). A polyclonal anti–rTs-CLP antibody was generated by immunization with rTs-CLP and Freund’s adjuvant, and subsequently used as the primary antibody for immunoblotting. This anti–rTs-CLP antibody specifically recognized approximately ~38 kDa band in both

T. spiralis ESPs and TSEs, consistent with the band detected by offspring sera (

Fig. 3C).

Although the predicted molecular weight of Ts-CLP is 27.5 kDa, the naive protein migrated around ~38 kDa in both ESPs and TSEs. This upward shift is plausibly attributable to post-translational modifications (e.g., glycosylation) and/or the presence of unprocessed peptide regions [

14,

15]. Notably, apparent molecular weight differences between native and recombinant forms are common when the latter are produced in cell-free systems lacking such modifications [

16]. To address the discrepancy between the predicted molecular weight of Ts-CLP (~27.5 kDa) and the larger size observed in native parasite extracts (~38 kDa), we performed in silico glycosylation site prediction using multiple tools (NetNGlyc, NetOGlyc, GlycoEP, and ISOGlyP). These analyses did not identify any strong canonical N-linked sites, although residues 204 (NYQ) and 232 (NSE) showed weak potential signals, with the latter approaching the threshold value (0.5). In addition, several serine/threonine residues (128, 135, 138, 144, 200, and 233) were suggested as potential O-linked glycosylation sites, but all with scores below the confidence cutoff. However, it should be noted that most currently available prediction tools were developed primarily on mammalian protein datasets, and their applicability to helminth proteins may therefore be limited. Taken together, these bioinformatic analyses cannot provide definitive evidence. They nevertheless suggest that partial or helminth-specific O-glycosylation may contribute to the observed size discrepancy. This underscores the need for experimental validation, including enzymatic deglycosylation or mass spectrometry. Together, these findings support the conclusion that the antigen recognized by maternally transferred antibodies in offspring is Ts-CLP, and further indicate that Ts-CLP is present in both secreted and somatic fractions of the

T. spiralis.

Collectively, these findings demonstrate the presence of antibodies reactive to Ts-CLP in the sera of offspring born to chronically infected mothers, despite the offspring themselves being uninfected. While the precise mechanism of transfer remains to be elucidated, and the possibility of passive transmission of parasite antigens cannot be excluded, the detection of IgG-class antibodies strongly suggests that maternal transfer of IgG is the most plausible explanation. Although our findings strongly suggest maternal IgG transfer, the precise route of antibody passage (placental versus lactational) remains unresolved. In the present study, we did not include IgG subclass-specific analyses, and while preliminary experiments confirmed the presence of total IgG in maternal milk, no distinct Ts-CLP–specific band was detected. The lack of subclass characterization and absence of definitive evidence for antigen-specific antibodies in milk, therefore, represent a limitation of this work. Future studies are required to determine whether IgG subclass distribution or milk-derived antibodies contribute to the vertical transfer of maternal immunity, thereby clarifying the mechanism of vertical antibody passage.

The functional relevance of these maternally derived antibodies also remains to be determined. It is not yet clear whether they confer protective immunity against T. spiralis or instead exert immunomodulatory effects. Future investigations should include functional validation of maternally transferred Ts-CLP antibodies, such as in vivo challenge experiments to assess protection and in vitro neutralization assays to evaluate potential immunomodulatory roles. Such approaches will be essential to establish the biological significance of these antibodies in host-parasite interactions.

Nevertheless, this study provides an initial basis for further investigation into passive immunity against helminths and the host recognition of parasite-derived immunoregulatory molecules.

Notes

-

Author contributions

Conceptualization: Yu HS. Data curation: Cho MK, Yu HS. Formal analysis: Cho MK. Funding acquisition: Cho MK. Methodology: Yu HS. Software: Cho MK, Yu HS. Supervision: Yu HS. Validation: Cho MK, Yu HS. Visualization: Cho MK, Yu HS. Writing – original draft: Cho MK. Writing – review & editing: Yu HS.

-

Conflict of interest

Hak Sun Yu serves as an editor of Parasites, Hosts and Diseases but had no involvement in the decision to publish this article. No other potential conflicts of interest relevant to this study were reported.

-

Funding

This work was supported by the research grant of the new professor of the Gyeongsang National University in 2024 (GNU-2024-240612).

Fig. 1.Identification of a Trichinella spiralis cystatin-like protein (Ts-CLP) recognized by maternal antibodies in offspring sera. (A, B) Immunoblot of T. spiralis excretory-secretory products (A) or total somatic extracts (B) probed with sera collected from 5-week-old uninfected offspring. Lane 1–4: offspring of normal females; Lane 5–8: offspring of chronically infected females. (C) The common immunoreactive band of approximately 38 kDa (gray arrowheads) was excised from SDS-PAGE and identified by MALDI-TOF/TOF mass spectrometry. Additional immunoreactive bands of different molecular weights are indicated by black arrowheads.

Fig. 2.Sequence features and structural modeling of Trichinella spiralis cystatin-like protein (Ts-CLP). (A) Nucleotide and deduced amino acid sequence of Ts-CLP. The predicted N-terminal signal peptide is subdivided into 3 regions: the N-terminal signal region (pink), hydrophobic core (green), and C-terminal signal peptide region (blue). The arrowhead indicates the predicted signal peptide cleavage site. The stop codon is marked with an asterisk. (B) Predicted tertiary structure of Ts-CLP generated using the AlphaFold Protein Structure Database. Structural prediction confidence is indicated by the color gradient from blue (high) to orange (low). (C) Predicted tertiary structure of Ts-CLP with domain segmentation based on The Encyclopedia of Domains. Domain 1 and Domain 2 are represented in distinct colors.

Fig. 3.Gene expression and immunological validation of Trichinella spiralis cystatin-like protein (Ts-CLP). (A) Relative transcript levels of Ts-CLP in 3 developmental stages of T. spiralis: newborn larvae (NBL), muscle larvae (ML), and adult worms (AW), analysed by RT-PCR. Data are presented as mean±SEM from 3 independent biological replicated (n=3), and statistical significance was assessed by Tukey’s test (*P<0.05, **P<0.01). (B) Recombinant Ts-CLP expressed in an ex vivo system, separated by SDS-PAGE, and visualized by Coomassie blue staining. (C) Immunoblot of Ts–excretory-secretory products (lane 1) or Ts–total somatic extracts (lane 2) probed with polyclonal anti–recombinant Ts-CLP antibody.

References

- 1. Cho M, Yu HS. Therapeutic potentials of Trichinella spiralis in immune disorders: from allergy to autoimmunity. Parasites Hosts Dis 2025;63:123-34. https://doi.org/10.3347/PHD.24086

- 2. Ilic N, Bojic-Trbojevic Z, Lundström-Stadelmann B, et al. Immunomodulatory components of Trichinella spiralis excretory-secretory products with lactose-binding specificity. EXCLI J 2022;21:793-813. https://doi.org/10.17179/excli2022-4954

- 3. Wang J, Tang B, You X, et al. Trichinella spiralis excretory/secretory products from adult worms inhibit NETosis and regulate the production of cytokines from neutrophils. Parasit Vectors 2023;16:374. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13071-023-05979-8

- 4. Kang SA, Yu HS. Proteome identification of common immunological proteins of two nematode parasites. Parasites Hosts Dis 2024;62:342-50. https://doi.org/10.3347/PHD.24027

- 5. Yuthithum T, Phuphisut O, Reamtong O, et al. Identification of the protease inhibitory domain of Trichinella spiralis novel cystatin (TsCstN). Parasites Hosts Dis 2024;62:330-41. https://doi.org/10.3347/PHD.24026

- 6. Li H, Qiu D, Yuan Y, et al. Trichinella spiralis cystatin alleviates polymicrobial sepsis through activating regulatory macrophages. Int Immunopharmacol 2022;109:108907. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intimp.2022

- 7. Acevedo N, Lozano A, Zakzuk J, et al. Cystatin from the helminth Ascaris lumbricoides upregulates mevalonate and cholesterol biosynthesis pathways and immunomodulatory genes in human monocyte-derived dendritic cells. Front Immunol 2024;15:1328401. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2024.1328401

- 8. Alghanmi M, Minshawi F, Altorki TA, et al. Helminth-derived proteins as immune system regulators: a systematic review of their promise in alleviating colitis. BMC Immunol 2024;25:21. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12865-024-00614-2

- 9. Khatri V, Chauhan N, Kalyanasundaram R. Parasite cystatin: immunomodulatory molecule with therapeutic activity against immune mediated disorders. Pathogens 2020;9:431. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens9060431

- 10. Lau AM, Bordin N, Kandathil SM, et al. Exploring structural diversity across the protein universe with The Encyclopedia of Domains. Science 2024;386:eadq4946. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.adq4946

- 11. Dall E, Hollerweger JC, Dahms SO, et al. Structural and functional analysis of cystatin E reveals enzymologically relevant dimer and amyloid fibril states. J Biol Chem 2018;293:13151-65. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.RA118.002154

- 12. Zalar M, Indrakumar S, Levy CW, et al. Studies of the oligomerisation mechanism of a cystatin-based engineered protein scaffold. Sci Rep 2019;9:9067. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-45565-6

- 13. Ochieng J, Chaudhuri G. Cystatin superfamily. J Health Care Poor Underserved 2010;21:51-70. https://doi.org/10.1353/hpu.0.0257

- 14. Wang G, de Jong RN, van den Bremer ETJ, Parren PWHI, Heck AJR. Enhancing accuracy in molecular weight determination of highly heterogeneously glycosylated proteins by native tandem mass spectrometry. Anal Chem 2017;89:4793-7. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.analchem.6b05129

- 15. Salazar VA, Rubin J, Moussaoui M, et al. Protein post-translational modification in host defense: the antimicrobial mechanism of action of human eosinophil cationic protein native forms. FEBS J 2014;281:5432-46. https://doi.org/10.1111/febs.13082

- 16. Fogeron ML, Lecoq L, Cole L, Harbers M, Böckmann A. Easy synthesis of complex biomolecular assemblies: wheat germ cell-free protein expression in structural biology. Front Mol Biosci 2021;8:639587. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmolb.2021.639587

Citations

Citations to this article as recorded by