Abstract

Plasmodium vivax merozoite surface protein-1 (PvMSP-1) is one of the major polymorphic markers for molecular epidemiological purposes. In particular, the interspecies conserved block 5–6 (ICB 5–6) of PvMSP-1 is a region exhibiting extensive genetic polymorphism. In this study, we analyzed polymorphic characters of the pvmsp-1 ICB 5–6 region from P. vivax isolates collected in 4 provinces of Vietnam (Dak Lak, Dak Nong, Gia Lai, and Khanh Hoa) between 2018 and 2022. A comparative analysis of pvmsp-1 ICB 5–6 sequences was also conducted between Vietnam and other endemic regions. A total of 139 pvmsp-1 ICB 5–6 sequences were obtained from 117 Vietnamese P. vivax isolates. Vietnam pvmsp-1 ICB 5–6 were clustered into 34 distinct haplotypes at the amino acid level, with the recombinant types being predominant. The pvmsp-1 ICB 5–6 from the Central Highlands, Dak Lak, Dak Nong, and Gia Lai, exhibited high genetic polymorphism, while the sequences from the South-Central region, Khanh Hoa, were less polymorphic. Highly diverse patterns of poly-glutamine (poly-Q) variants were identified in Vietnam pvmsp-1 ICB 5–6. Comparable features of genetic polymorphism were also identified in the global pvmsp-1 ICB 5–6 populations. Phylogenetic analysis of global pvmsp-1 ICB 5–6 revealed no significant country-specific or region-specific clustering. This study suggests that Vietnam pvmsp-1 ICB 5–6 exhibited a substantial genetic diversity with regional variations, implying the genetic heterogeneity of the Vietnamese P. vivax population. These findings emphasize the importance of continuous molecular surveillance to understand the genetic nature of the parasite in the country.

-

Key words: Plasmodium vivax, PvMSP-1 ICB 5–6, genetic polymorphism, Vietnam

Introduction

Malaria is a life-threatening vector-borne disease caused by apicomplexan parasites belonging to the genus

Plasmodium. Global efforts to combat malaria have continuously reduced the incidence and mortality of malaria worldwide since 2000. However, an estimated 263 million cases and about 600,000 deaths have been reported globally in 2023 [

1], imposing a continuous substantial global health burden. Among the human-infecting

Plasmodium species,

P. vivax is the most widely distributed species worldwide, particularly prevalent in Asia and South America [

1]. Vietnam is a country in the Greater Mekong Subregion (GMS), where malaria is endemic. Like the other countries in the GMS, Vietnam also aims to eliminate malaria by 2030, and has achieved significant malaria reduction over the past 2 decades [

1]. However, the Central Highlands and the South-Central regions remain malaria hot spots.

P. falciparum and

P. vivax are the major species in the areas [

2]. Although

P. falciparum cases have remarkably declined,

P. vivax is still prevalent, and severe cases are also identified [

3]. A recent unprecedented large outbreak of

P. malariae, antimalarial drug resistance, and asymptomatic submicroscopic

P. falciparum and

P. vivax are new challenges in eliminating malaria in Vietnam [

4-

6].

The persistent prevalence of vivax malaria is largely attributed to unique biological features of

P. vivax, such as early gametocyte formation and dormant liver-stage hypnozoites, which may lead to relapses months or years after primary infection [

7]. These underscore the urgent necessity of investigation on the genetic structure of the parasite population to understand the diversity, distribution, and dynamics of natural

P. vivax populations, which could be supportive of developing effective vaccine strategies in combating the ongoing challenges posed by

P. vivax [

8].

Merozoite surface protein-1 (MSP-1) is a major surface protein of merozoites of

Plasmodium species, playing a critical role in erythrocyte invasion [

9,

10].

P. vivax MSP-1 (PvMSP-1) is a 200-kDa protein encoded by the

pvmsp-1 gene and is regarded as a leading vaccine candidate targeting

P. vivax [

11-

14]. Cross-species sequence analysis of

msp-1 from

P. vivax,

P. falciparum, and

P. yoelii revealed 10 interspecies conserved blocks (ICBs) that include 8 major polymorphic regions among these

Plasmodium parasites [

15]. In particular, the ICB 5–6 region of the gene, encompassing highly polymorphic traits caused by insertions, deletions, intra-allelic recombination, and point mutations, has been identified as a reliable genetic polymorphic marker [

16]. While genetic polymorphism studies of

pvmsp-1 ICB 5–6 have been undertaken in various endemic regions [

17-

24], information on the Vietnamese

P. vivax population remains scarce.

This study aimed to characterize the genetic diversity of pvmsp-1 ICB 5–6 in P. vivax isolates collected in Vietnam to understand the genetic nature of P. vivax population in the country.

Methods

Ethics statement

The study protocol was approved by the Ethical Review Committee of the Ministry of Health, Institute of Malariology, Parasitology and Entomology Quy Nhon, Vietnam (approval No. 386/VSR-LSDT, 45/VSR-NCDT, and 637/VSR-NCDT).

Blood samples

A total of 117 blood samples obtained from

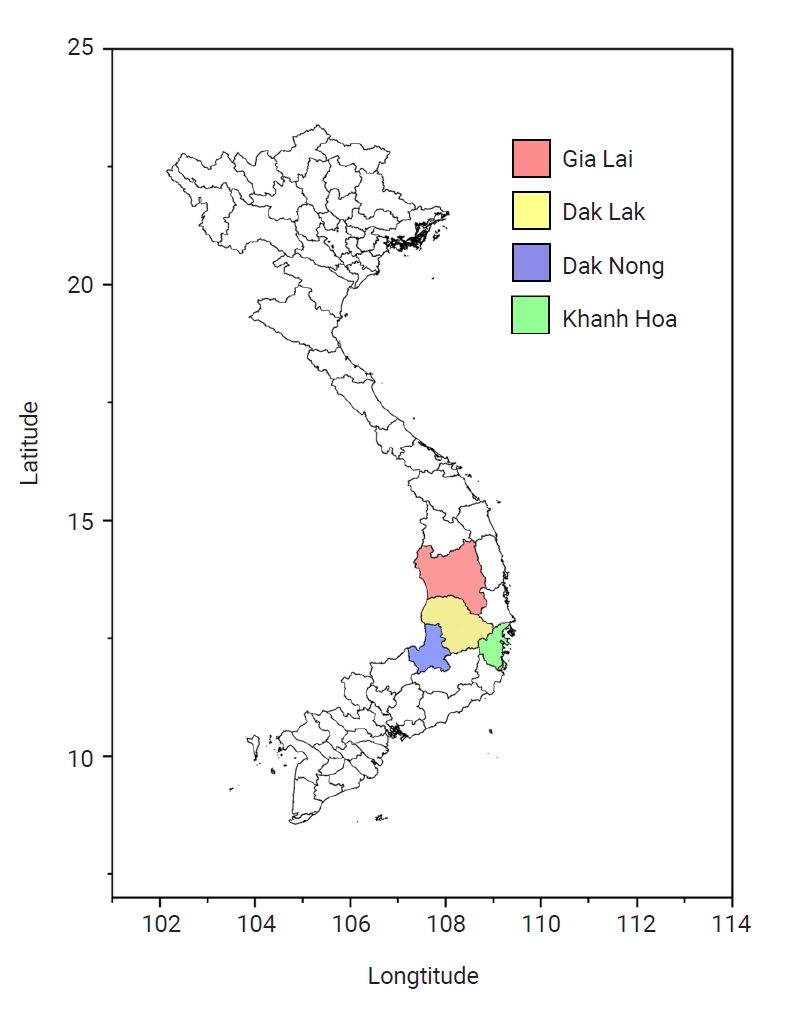

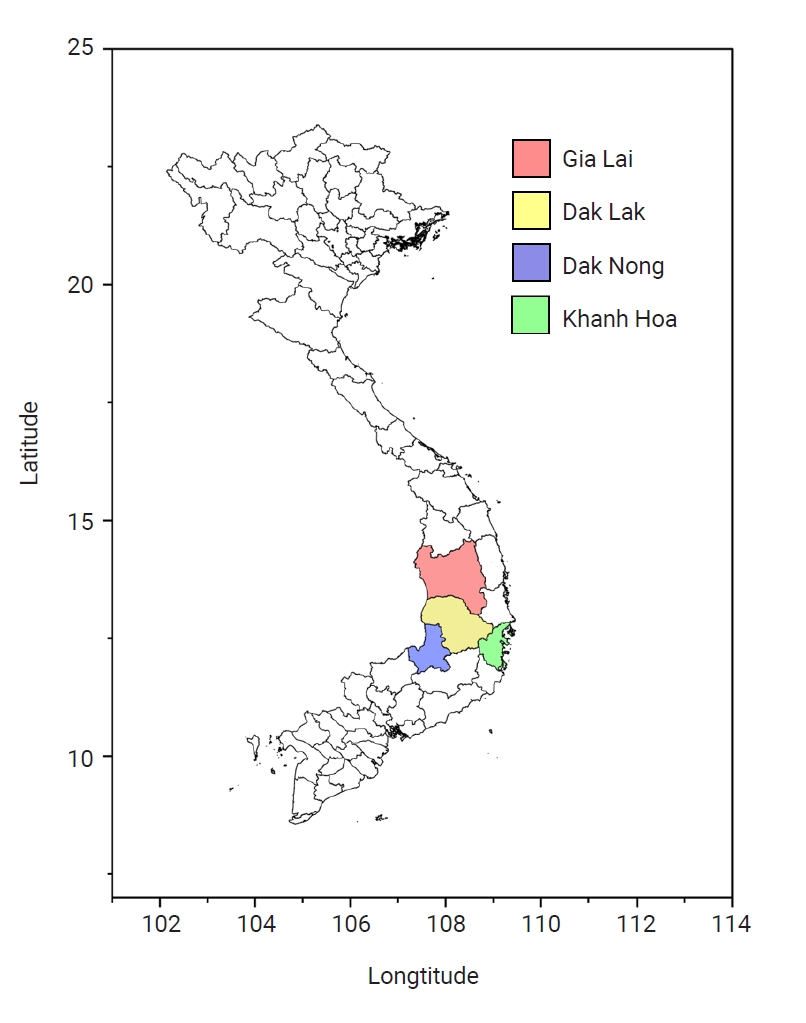

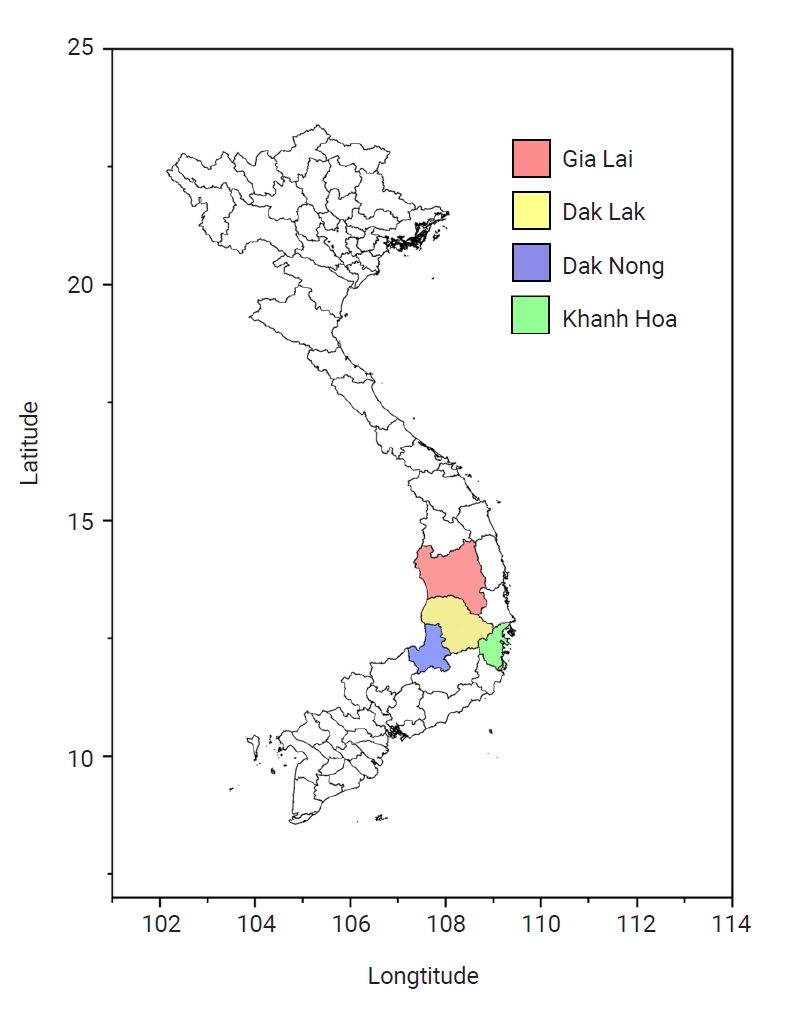

P. vivax-infected malaria patients in the Central Highlands (Gia Lai, Dak Nong, and Dak Lak provinces) and the South-Central region (Khanh Hoa province) of Vietnam in 2018–2022 were used in this study (

Fig. 1).

P. vivax infection was diagnosed by a rapid diagnostic test (SD-Bioline Malaria Pf/Pv HRP2/pLDH Ag) and microscopic examination of thick and thin blood smears. Before antimalarial drug administration, 2 or 3 drops of finger-prick blood were taken from each patient, spotted on Whatman 3 MM filter paper (GE Healthcare), and dried. Verbal informed consent was obtained from each participant before blood collection.

Genomic DNA of

P. vivax was extracted from each dried blood spot using the QIAamp DNA Blood Kit (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer’s protocols. Genomic DNA was eluted in 50 μl of the elution buffer in the kit, and DNA quality was assessed using a DS-11 spectrophotometer (DeNovix). The gene fragment covering

pvmsp-1 ICB 5–6 was amplified via a nested PCR using specific primer sets and thermal cycles described previously [

19]. To enhance fidelity of amplification, Ex

Taq DNA polymerase (Takara), possessing proofreading activity, was used in all amplification steps. Multiple amplicons with different sizes were identified in some samples, implying multiple infections. Each PCR product was cloned into the T&A cloning vector (Real Biotech Corporation) and transformed into

Escherichia coli DH5α competent cells. The recombinant plasmids containing the insert of expected size were selected by colony PCR. Plasmids from selected clones were purified and subjected to bidirectional sequencing with M13 forward and reverse primers. To ensure sequence accuracy and minimize potential sequencing artifacts, plasmids isolated from at least 2 independent clones for each isolate were sequenced. Nucleotide sequences of

pvmsp-1 ICB 5–6 obtained in this study have been deposited in the GenBank database under the accession numbers PX388009–PX388147.

The nucleotide and deduced amino acid sequences of Vietnam

pvmsp-1 ICB 5–6 were analyzed using EditSeq and SeqMan programs in the DNSTAR package (DNASTAR) and MEGA7 [

25]. The resulting sequences were further analyzed by comparing 2 reference sequences, Sal I (XM_001614792) and Belem (AF435594).

To assess the genetic polymorphisms and phylogenetic relationships between Vietnam and global

pvmsp-1 ICB 5–6 populations, publicly available nucleotide sequences of global

pvmsp-1 ICB 5–6 were extracted from GenBank databases: Myanmar (

n=83, MW383137–MW383219), Thailand (

n=170, GQ890872–GQ891041), Korea (

n=255, KU893351–KU893605), Pakistan (

n=75, OP313607–OP313681), Turkey (

n=30, AB564559–AB564588), Azerbaijan (

n=36, AY789657–AY789692), Kyrgyzstan (

n=16, MH201430–MH201445), and Mexico (

n=14, JX443532–JX443545). Phylogenetic tree of global

pvmsp-1 ICB 5–6 was constructed by using the Maximum Likelihood method in MEGA7 with 1,000 bootstrap replicates [

25], and the final topology was visualized using the Interactive Tree of Life (iTOL) platform (

https://itol.embl.de/). The analysis of molecular variance for global

pvmsp-1 ICB 5–6 sequences was performed with Arlequin 3.5, and the significance of variance levels was evaluated using 1,000 permutations [

26].

Results

Genetic polymorphism of Vietnam pvmsp-1 ICB 5–6

A total of 139

pvmsp-1 ICB 5–6 sequences were obtained from 117 Vietnamese

P. vivax isolates, suggesting an estimated multiplicity of infection value of 1.19. The

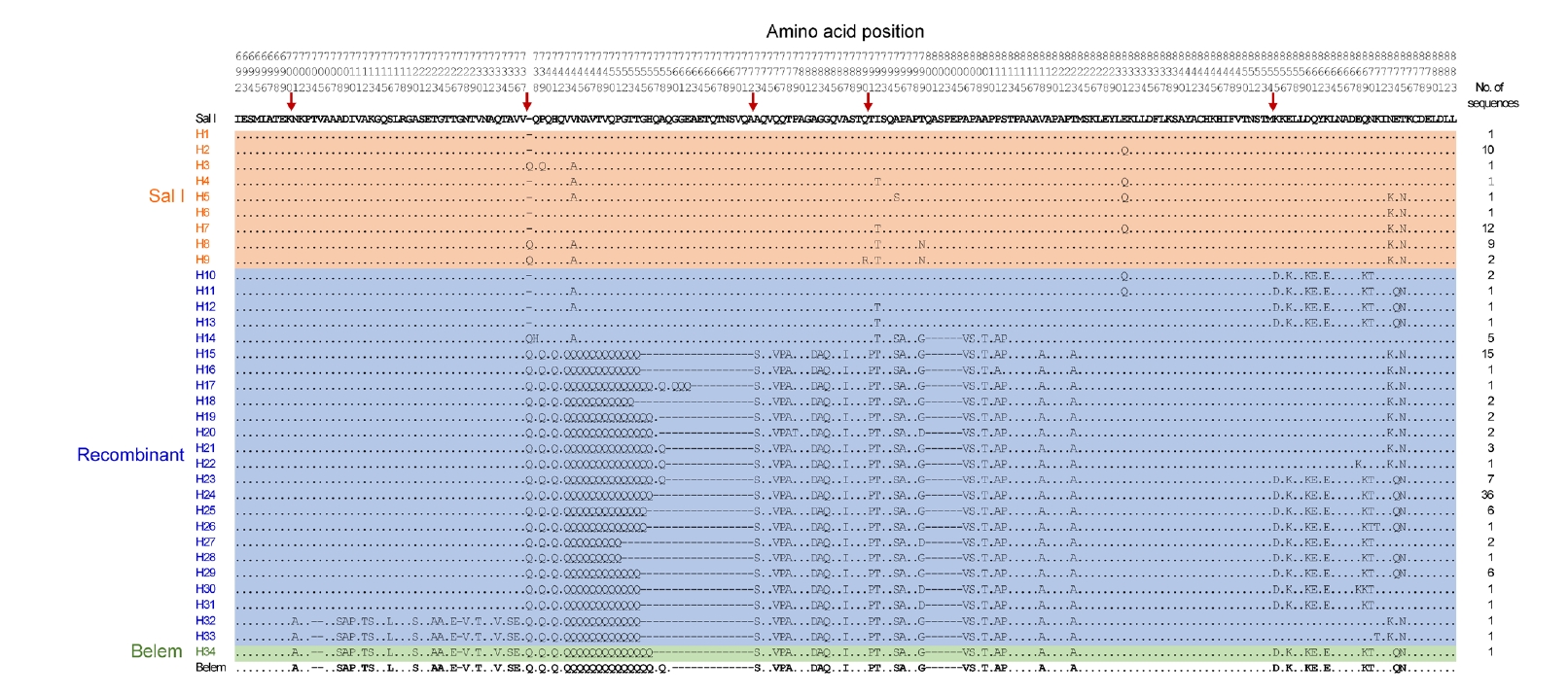

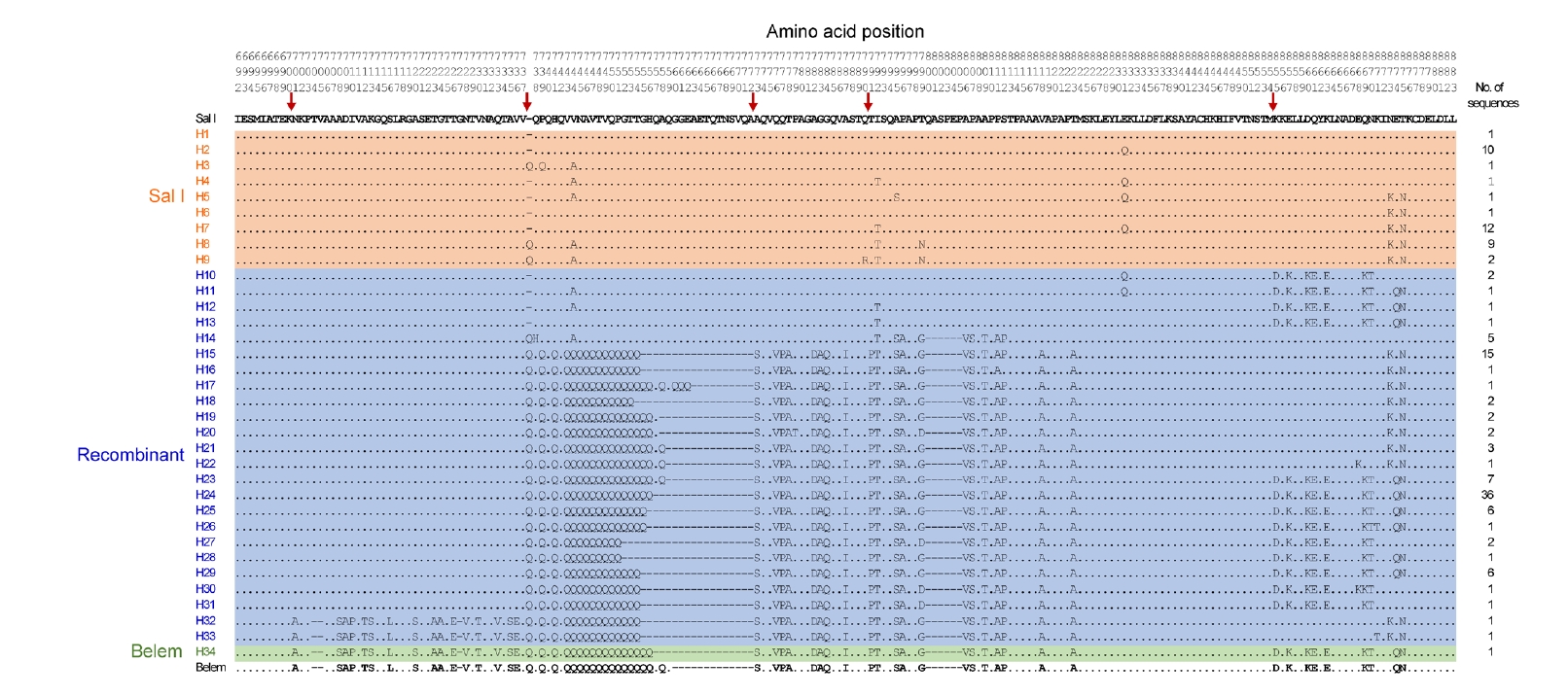

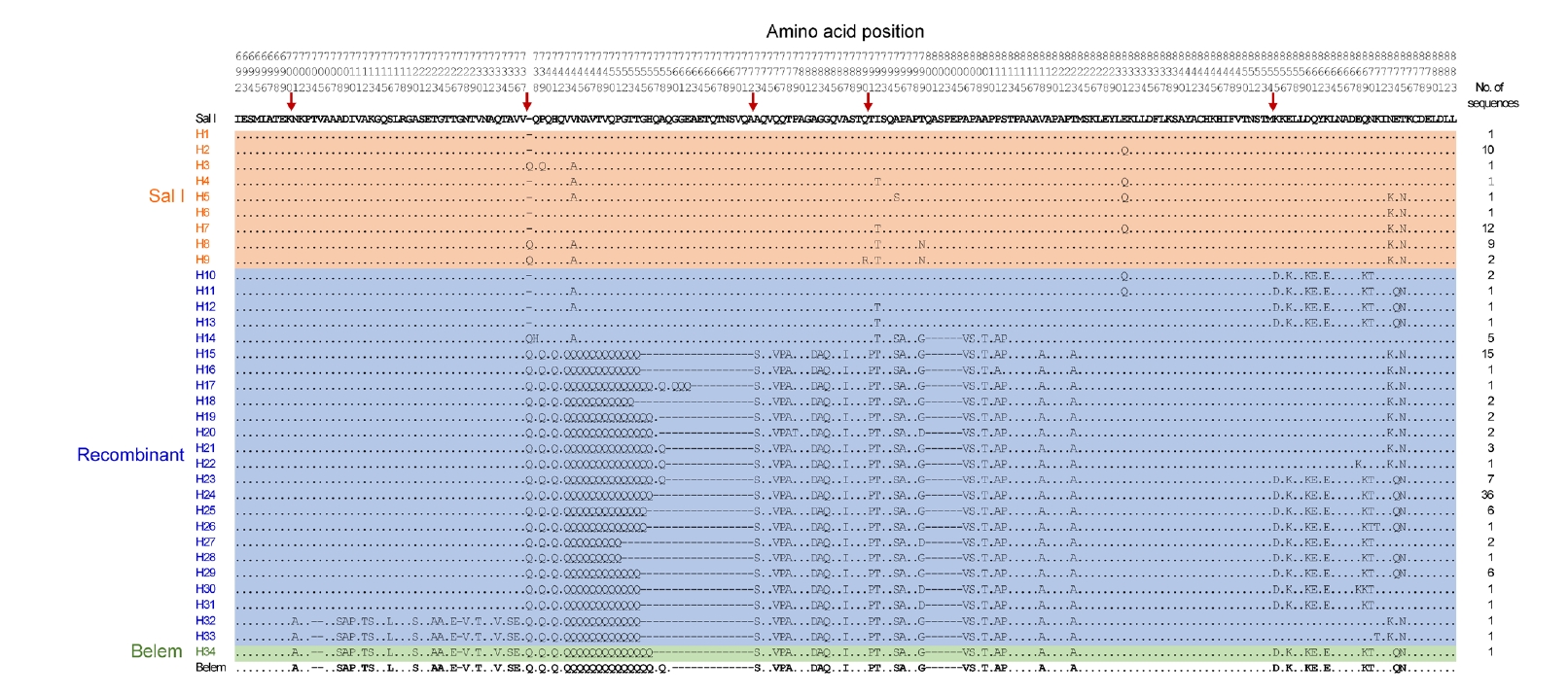

pvmsp-1 ICB 5–6 sizes were not equal, showing size polymorphisms ranging from 510 to 591 bp. Sequence analysis of the Vietnam

pvmsp-1 ICB 5–6 sequences at the amino acid level revealed that they were clustered into 34 distinct haplotypes, which were further classified into 3 different allele types: Sal I, recombinant, and Belem (

Fig. 2). Nine haplotypes (H1–H9) were classified into Sal I types, while 24 haplotypes (H10–H33) were recombinant types. Only 1 haplotype (H34) was classified into the Belem type. Recombinant types exhibited the greatest polymorphisms and were prevalent, occupying 72.0% of the sequences (100/139), followed by Sal I types of 27.3% (38/139) and a Belem type of 0.7% (1/139). Haplotype 24 (H24) was the most prevalent, accounting for 25.9% (36/139). In Sal I types, H1 shared the identical amino acid sequence with Sal I reference (XM_001614792), while other haplotypes (H2–H9) had amino acid changes, such as P739Q, V744A, Q790R, I792T, A795S, T799N, E831Q, N873K, and T875N, caused by non-synonymous single nucleotide polymorphisms and an insertion of a glutamine (Gln, Q) residue between amino acid positions 737 and 738. Recombinant types were generated by potential recombination between Sal I and Belem types at 5 positions, and revealed highly diverse patterns of poly-Gln (poly-Q) repeats. Nine amino acid substitutions, including Q738H, V744A, I792T, T799D, E831Q, E868K, K871T, N873K, and T875N, were also found in recombinant haplotypes. H34 shared a highly conserved sequence with the Belem reference (AF435594), and had a different poly-Q pattern. The frequencies of

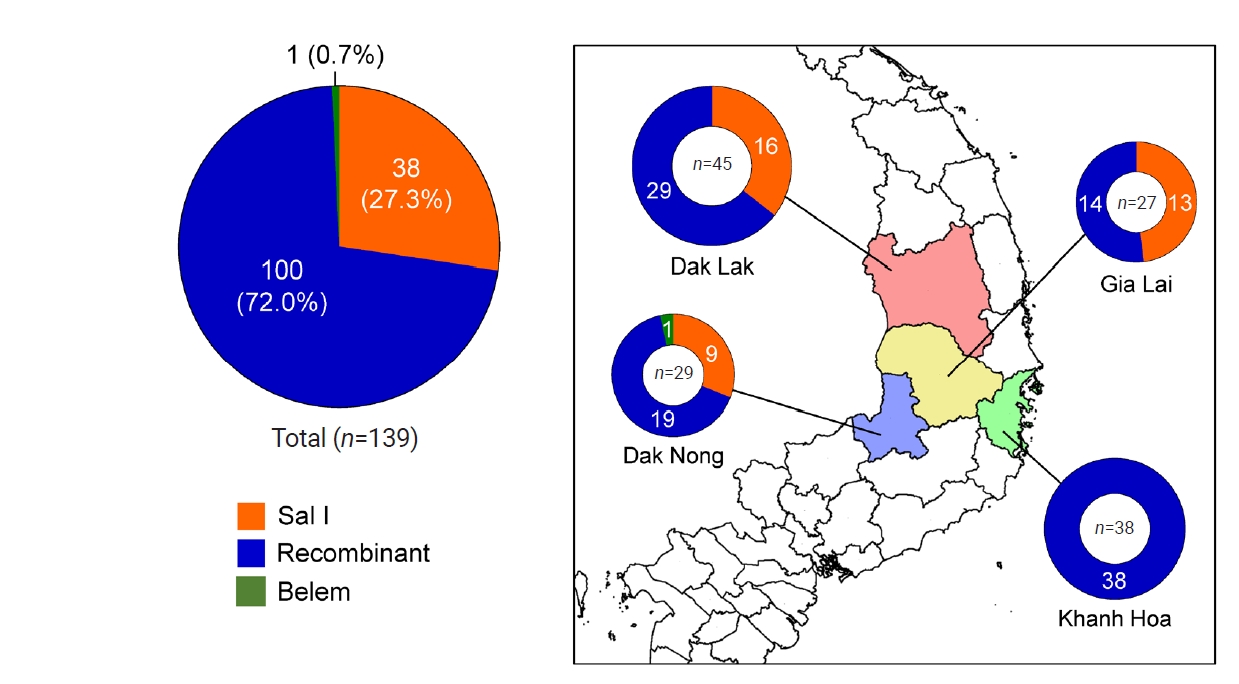

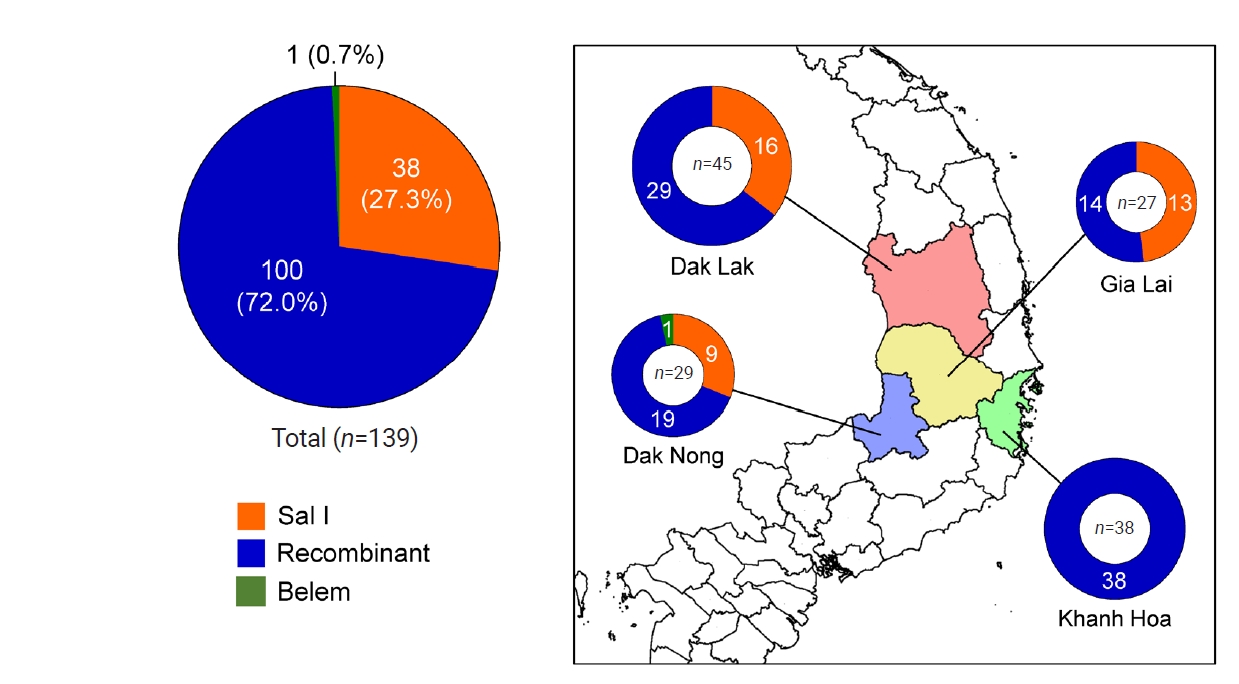

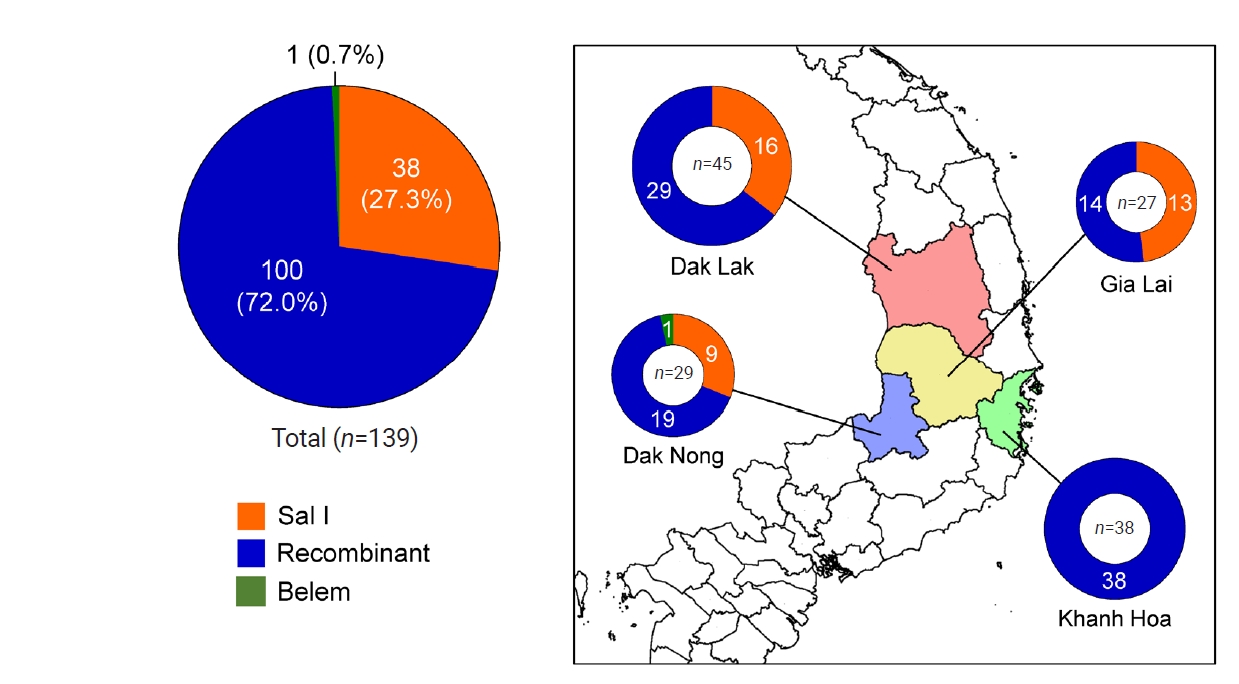

pvmsp-1 ICB 5–6 allelic types differed by province (

Fig. 3). Three provinces in the Central Highlands, Dak Lak, Gia Lai, and Dak Nong, revealed mixed allelic types, in which recombinant types were prevalent. The Belem type was identified only in Dak Nong, while only recombinant types were identified in Khanh Hoa province. The

pvmsp-1 ICB 5–6 displayed pronounced genetic variability in the poly-Q repeat region due to unstructured tandem Q repeats, particularly in recombinant and Belem types. The number of Qs in poly-Q repeats differed in Vietnam

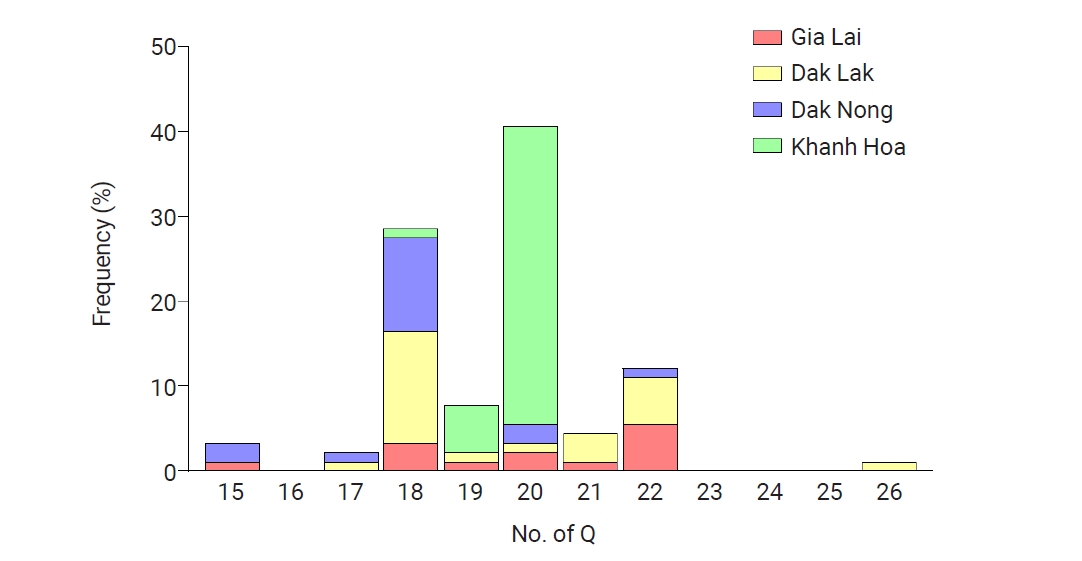

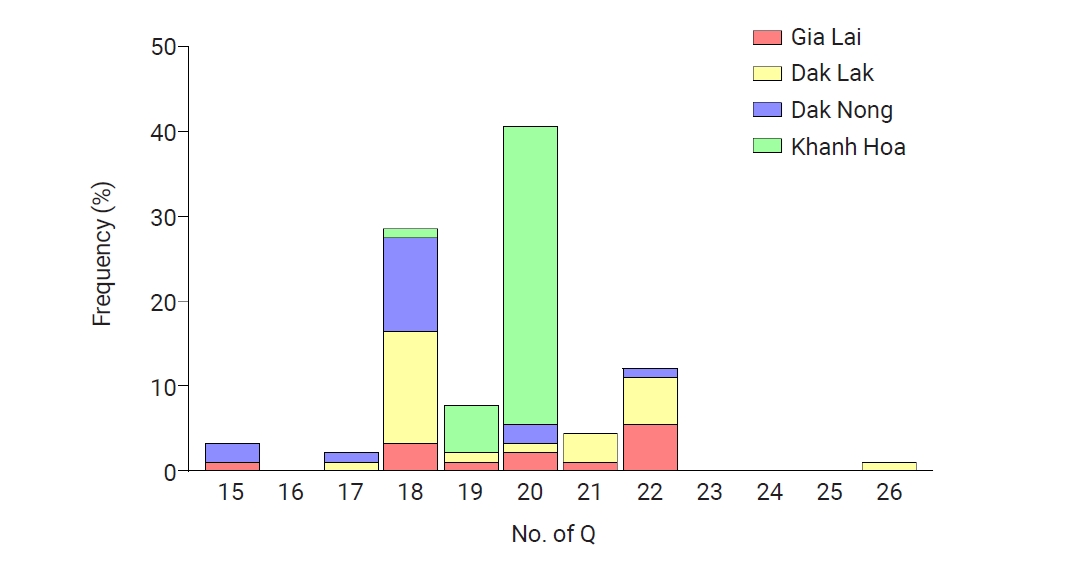

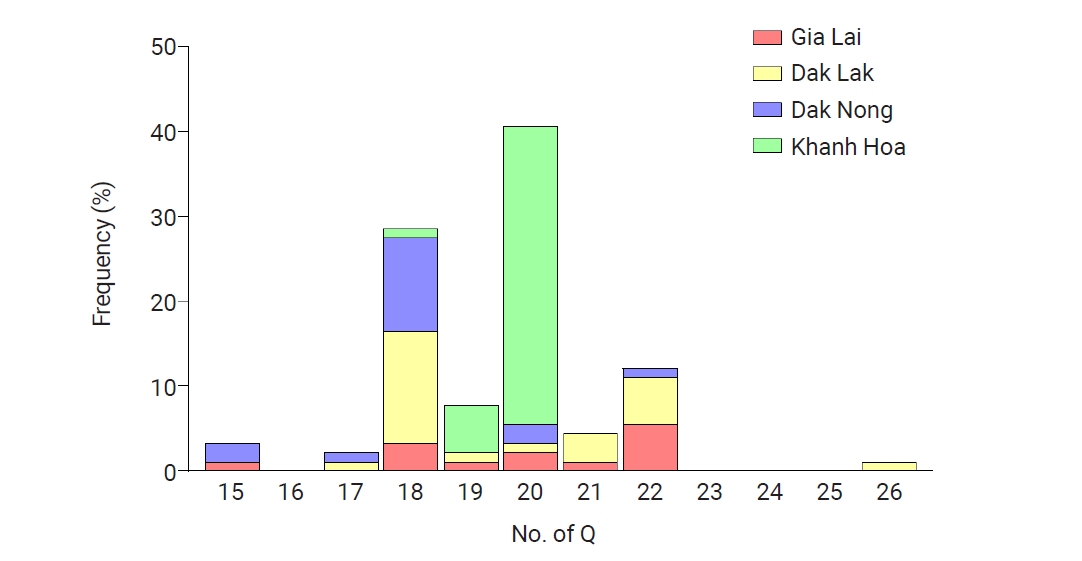

pvmsp-1 ICB 5–6, ranging from 15 to 26 (

Fig. 4). The

pvmsp-1 ICB 5–6 from Khanh Hoa showed less polymorphic features than those from Gia Lai, Dak Lak, and Dak Nong: only 3 types of poly-Qs, 18, 19, and 20 Qs, were identified in Khanh Hoa, while more diverse types of poly-Qs were observed in Gia Lai (17, 18, 19, 20, and 21 Qs), Dak Lak (17, 18, 19, 20, 21, and 26 Qs), and Dak Nong (15, 17, 18, 20, and 22 Qs). Overall, 18 and 20 Qs were the most predominant poly-Q repeats in Vietnam

pvmsp-1 ICB 5–6.

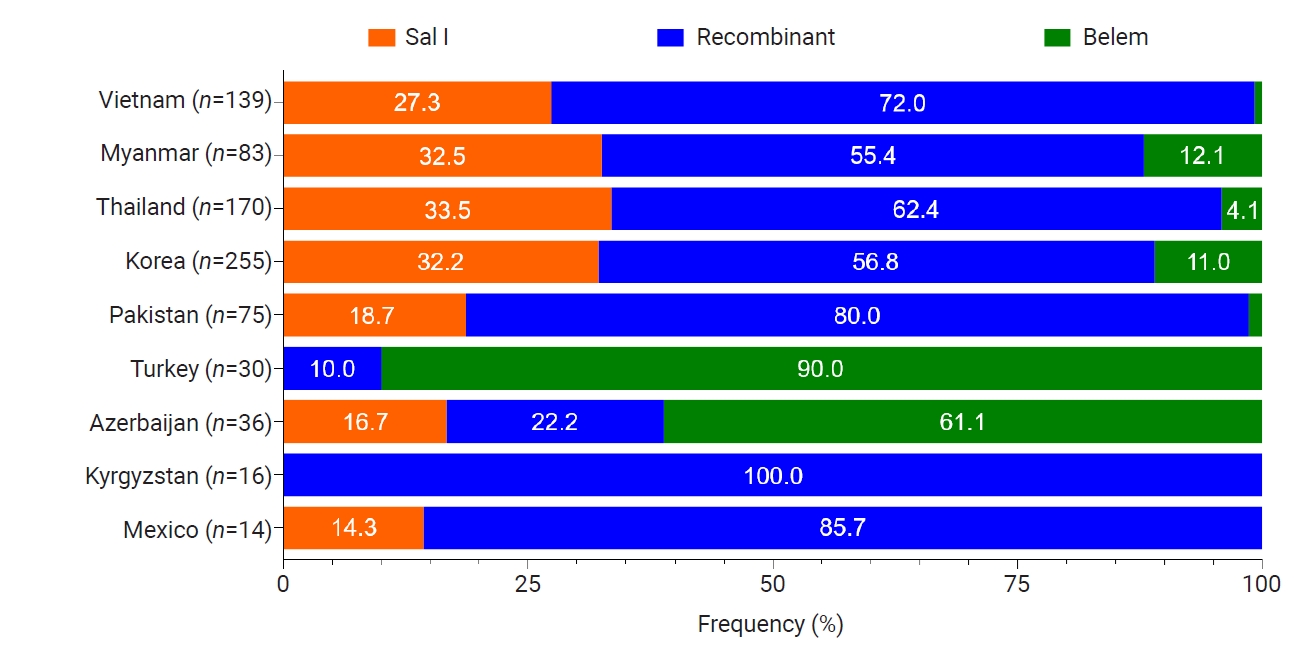

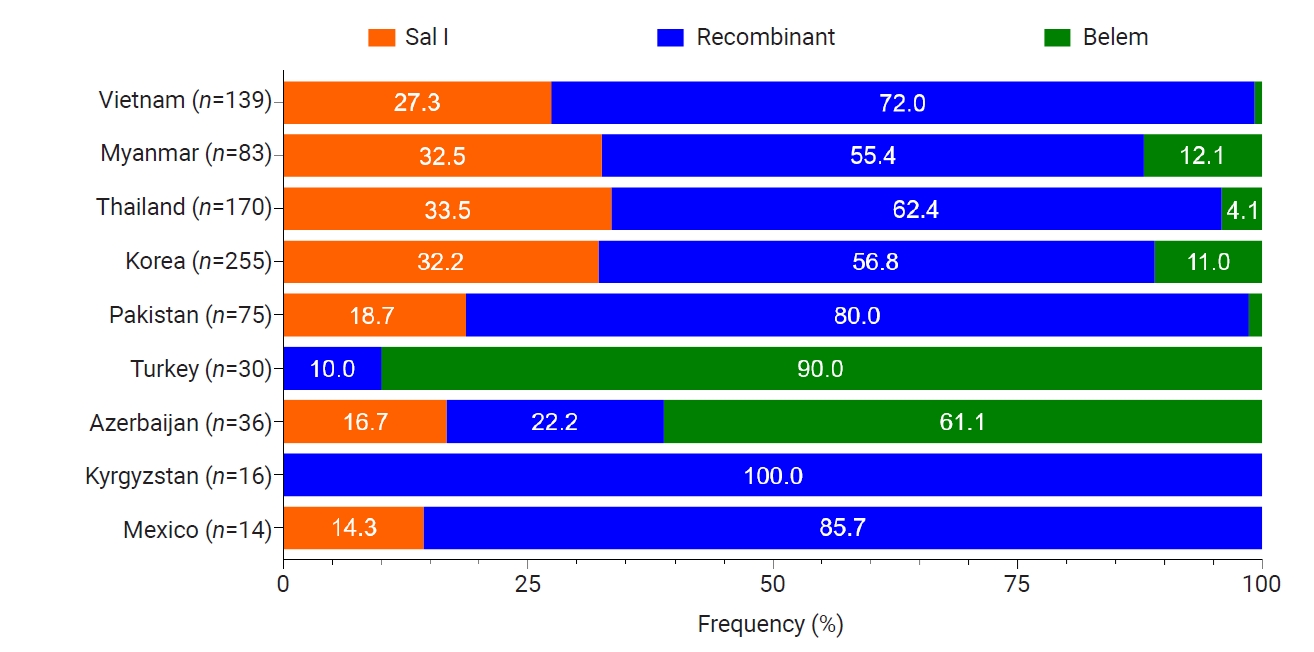

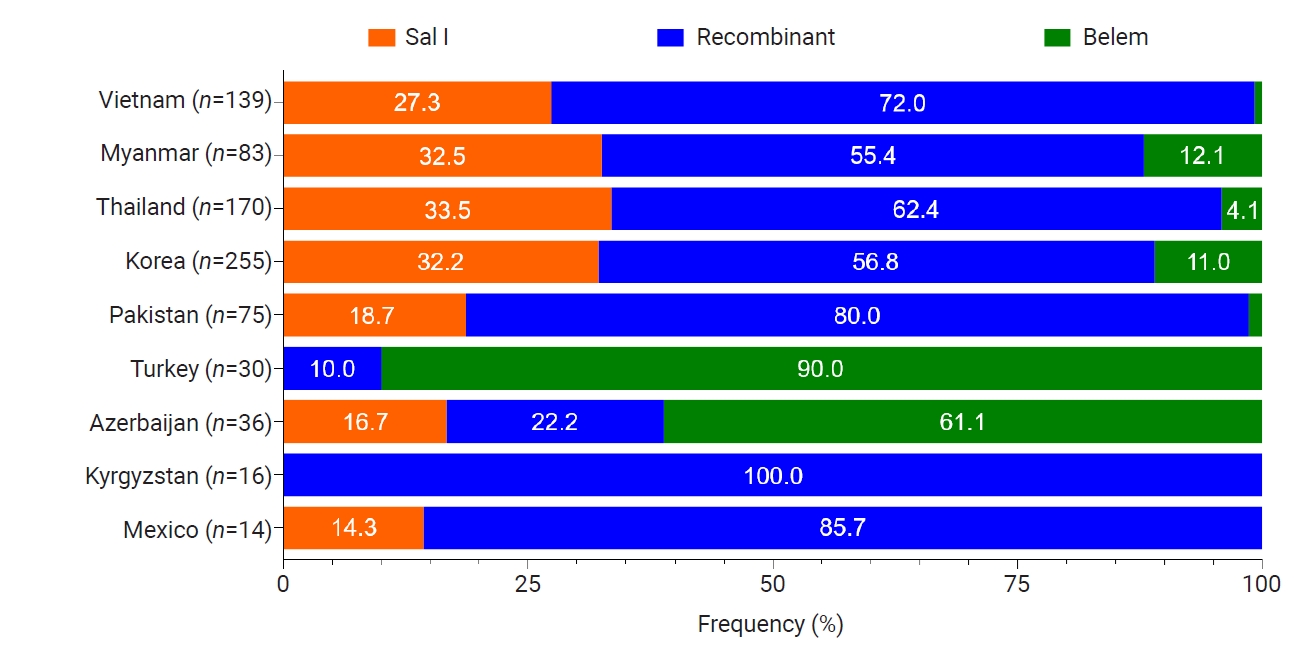

Global

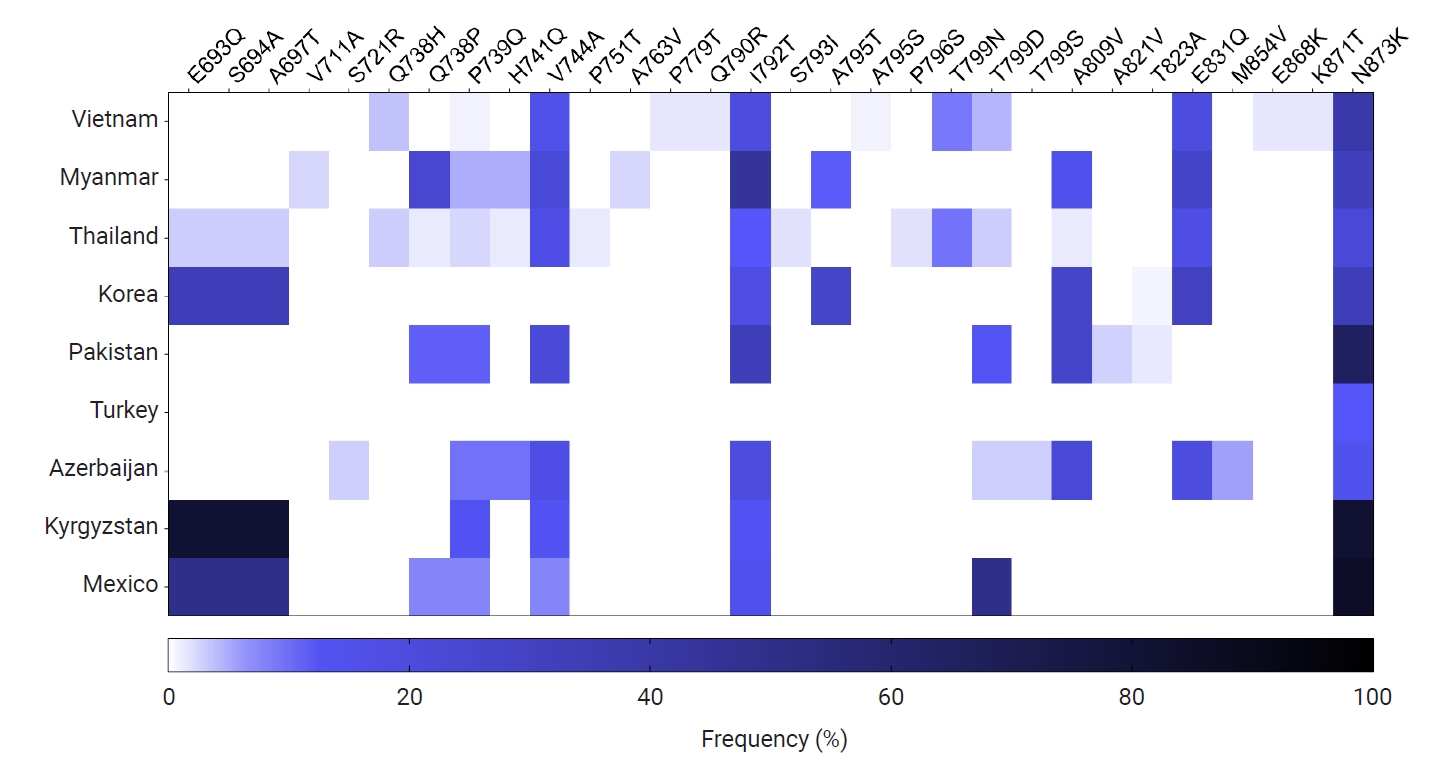

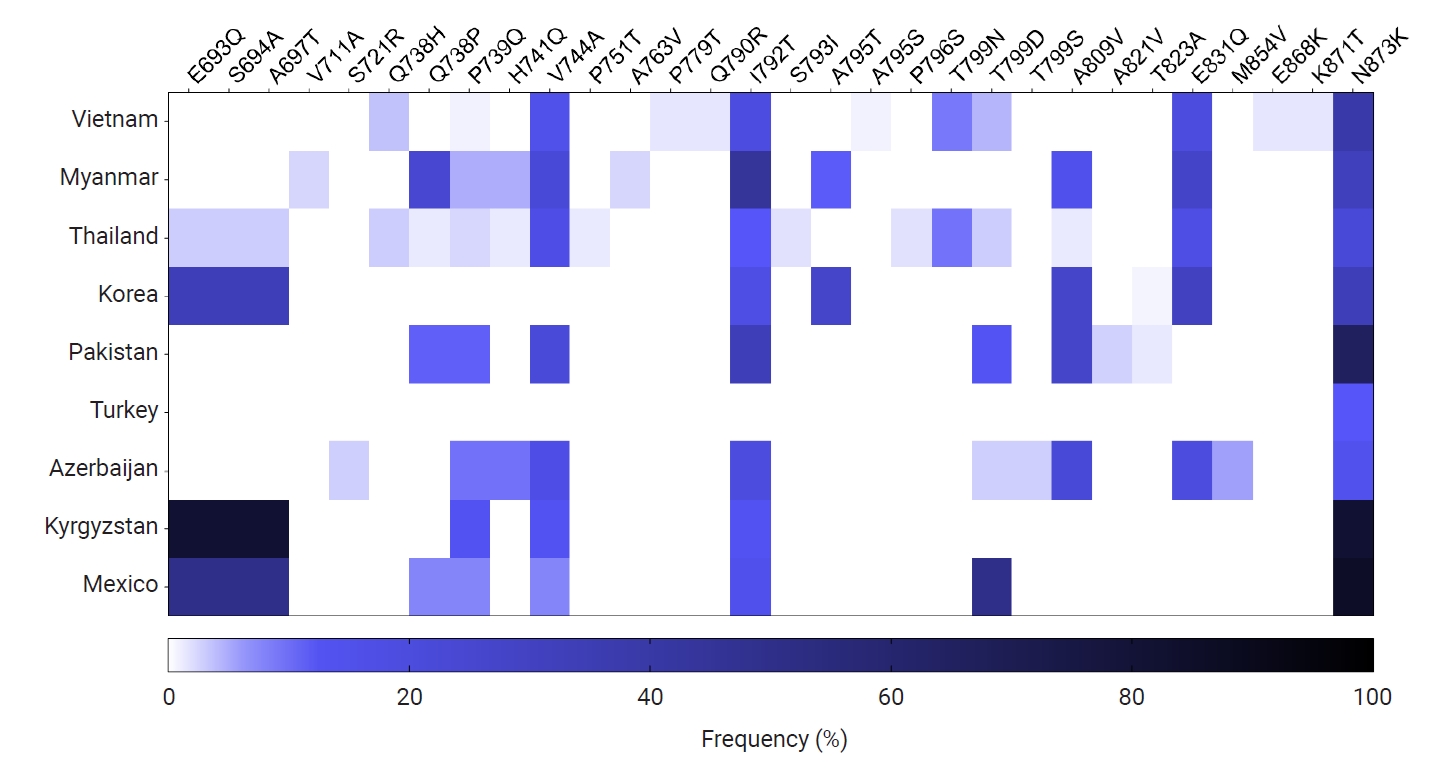

pvmsp-1 ICB 5–6 also showed great genetic polymorphisms, but the frequencies of 3 allelic types differed by country (

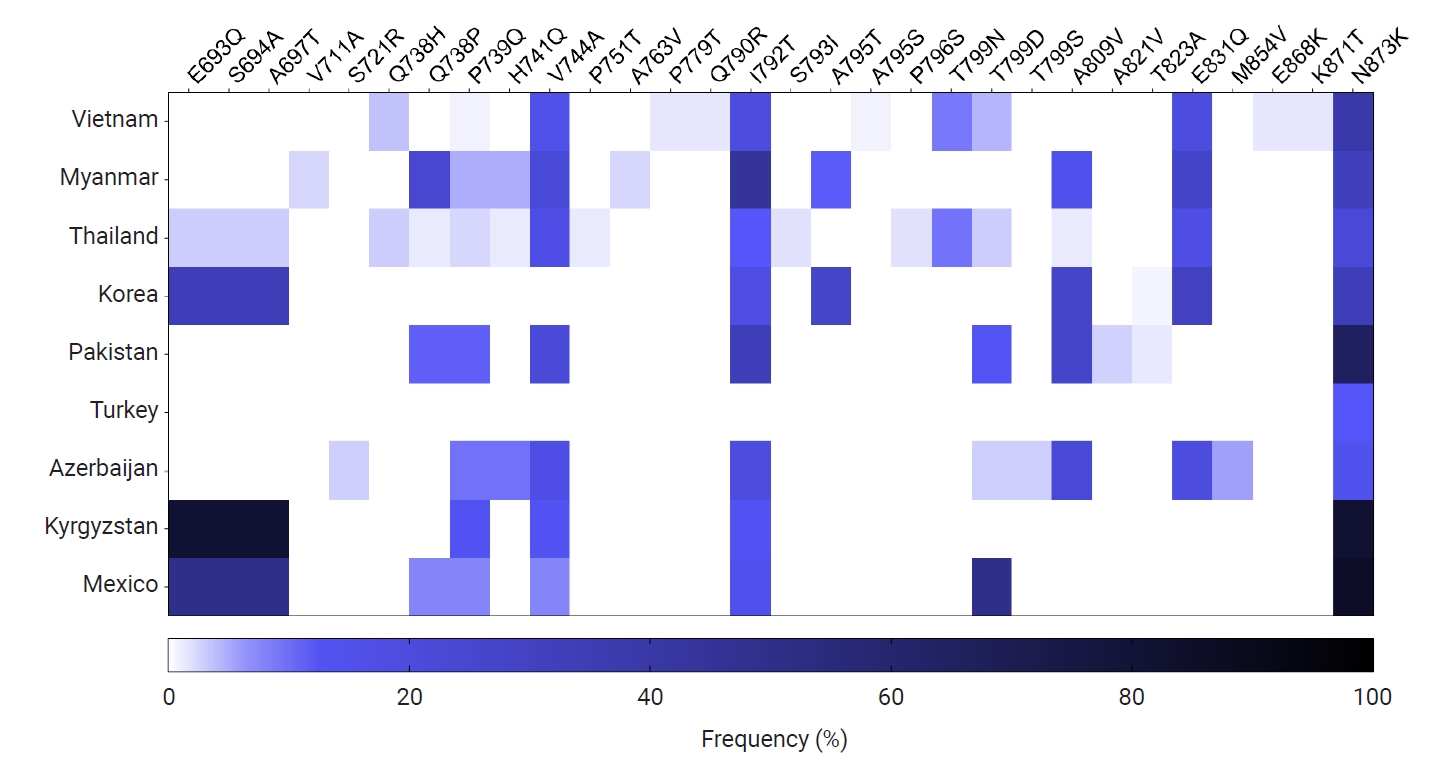

Fig. 5). Recombinant types were the most prevalent allelic types in Vietnam, Myanmar, Thailand, Korea, Pakistan, Kyrgyzstan, and Mexico, while Belem types were significant in Turkey and Azerbaijan. Amino acid changes identified in the global

pvmsp-1 ICB 5–6 were also comparatively analyzed (

Fig. 6). Overall profiles of amino acid changes in the global populations differed by country. However, N873K was commonly detected in all countries analyzed in this study, with a frequency ranging from 10.0% (Turkey) to 85.7% (Mexico). I792T was also identified in

pvmsp-1 ICB 5–6 from countries except for Turkey. E693Q, S694A, A697T, Q738P, P739Q, V744A, T799D, A809V, and E831Q were also detected in

pvmsp-1 ICB 5–6 of more than 4 countries. A few amino acid changes with low frequencies were detected in country-specific manners, in which P779T, Q790R, A795S, E868K, and K871T were specific in Vietnam

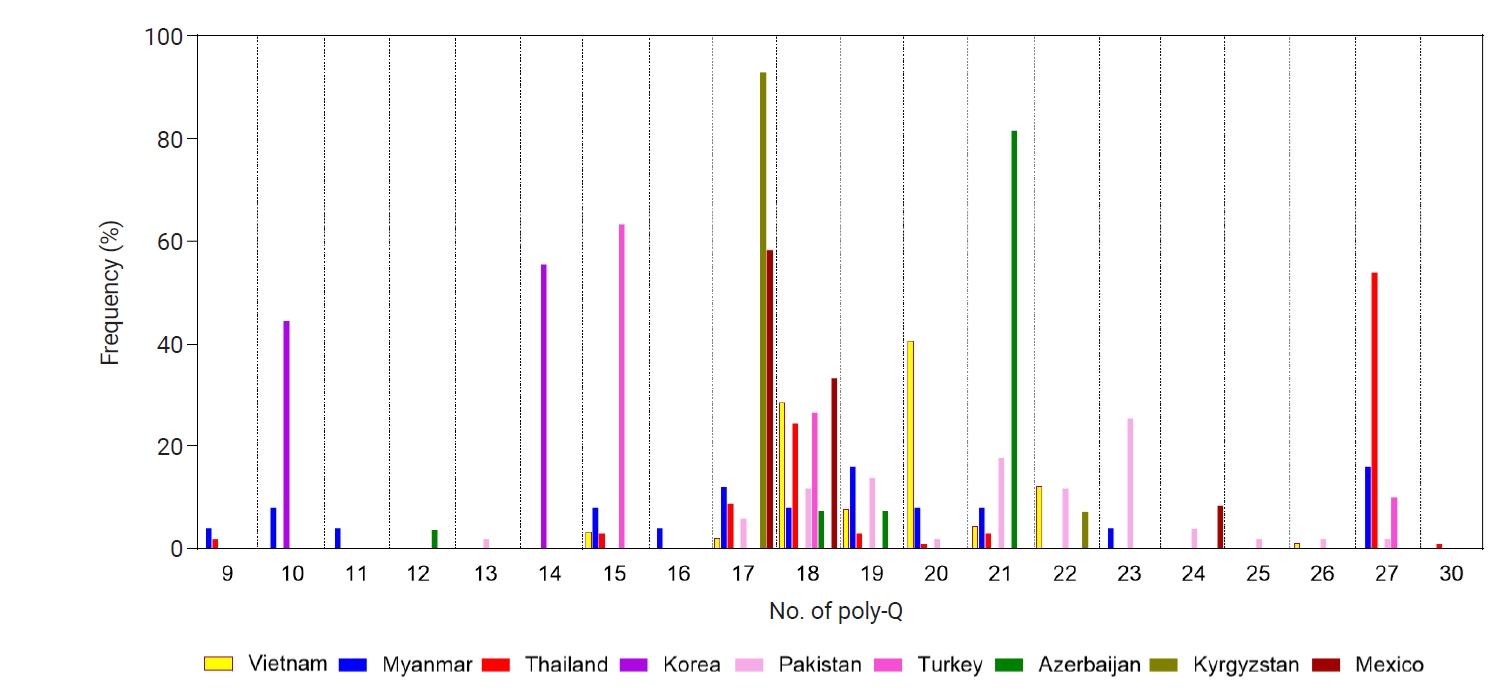

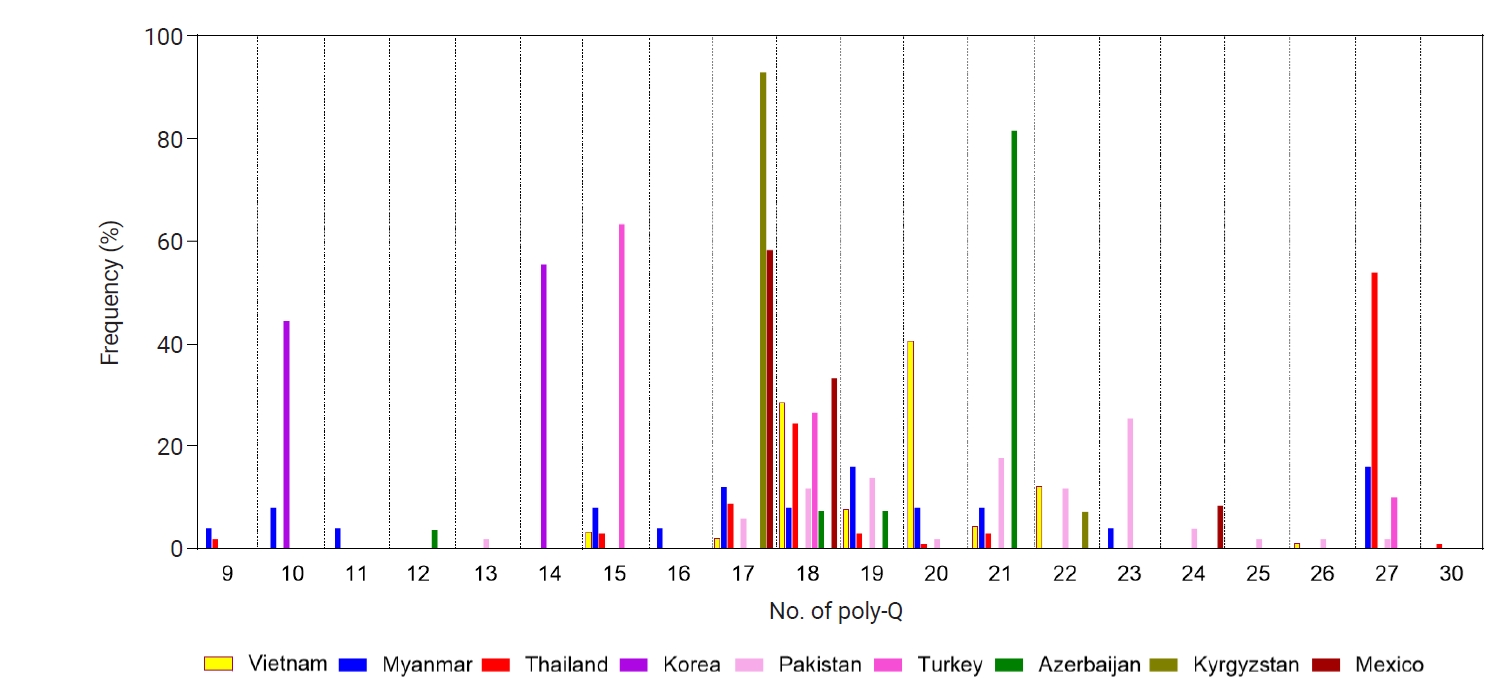

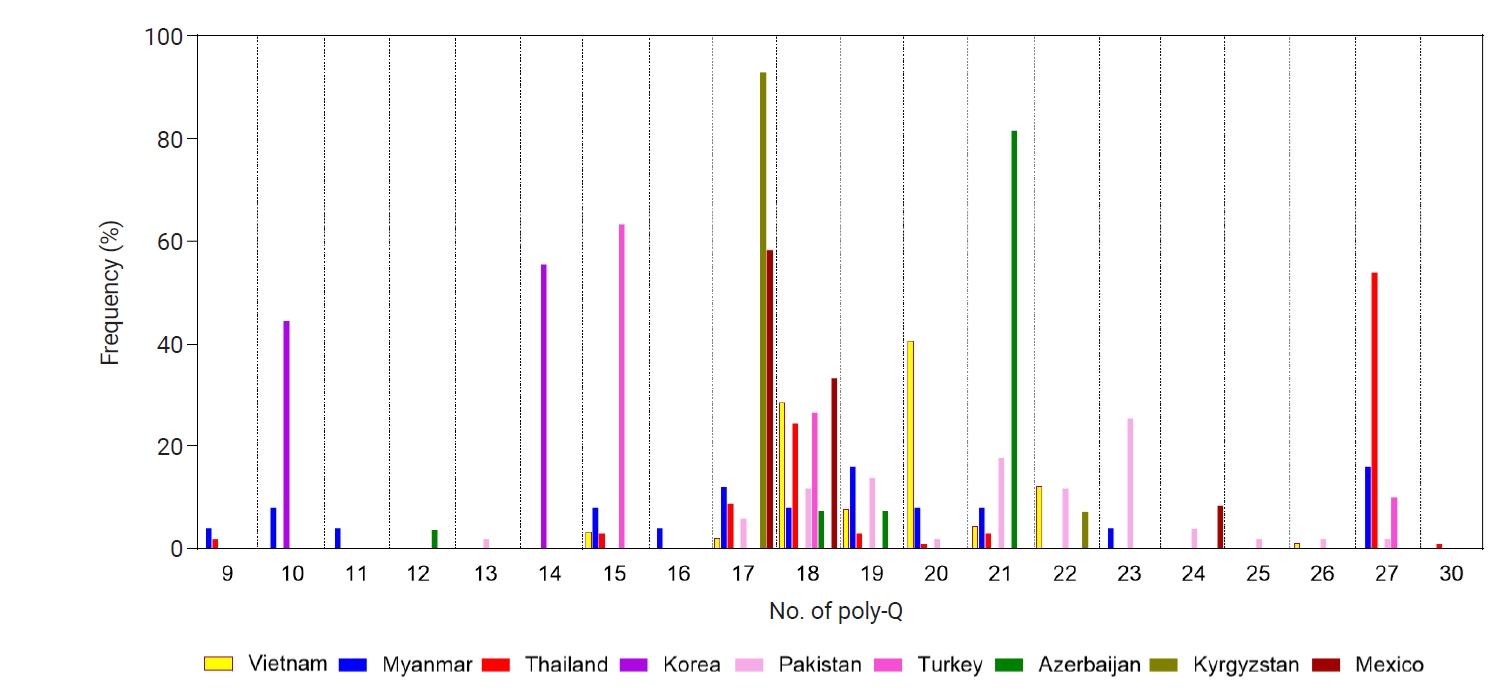

pvmsp-1 ICB 5–6. Global

pvmsp-1 ICB 5–6 showed a high level of polymorphisms in the poly-Q repeats region. The Q count in poly-Q repeats exhibited great diversity in the global populations, from 9 to 30 (

Fig. 7). The most common number of Q was 18, which was found in

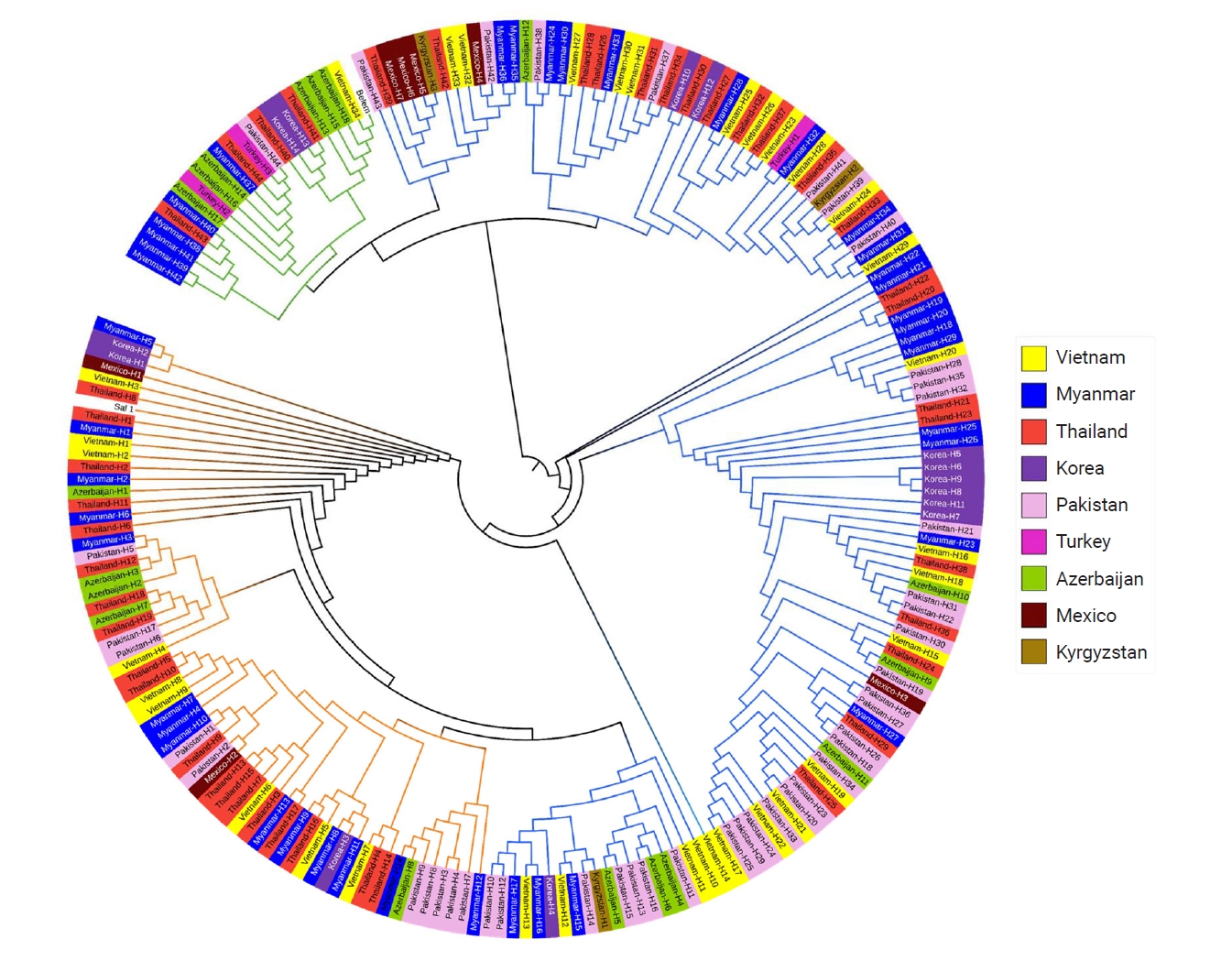

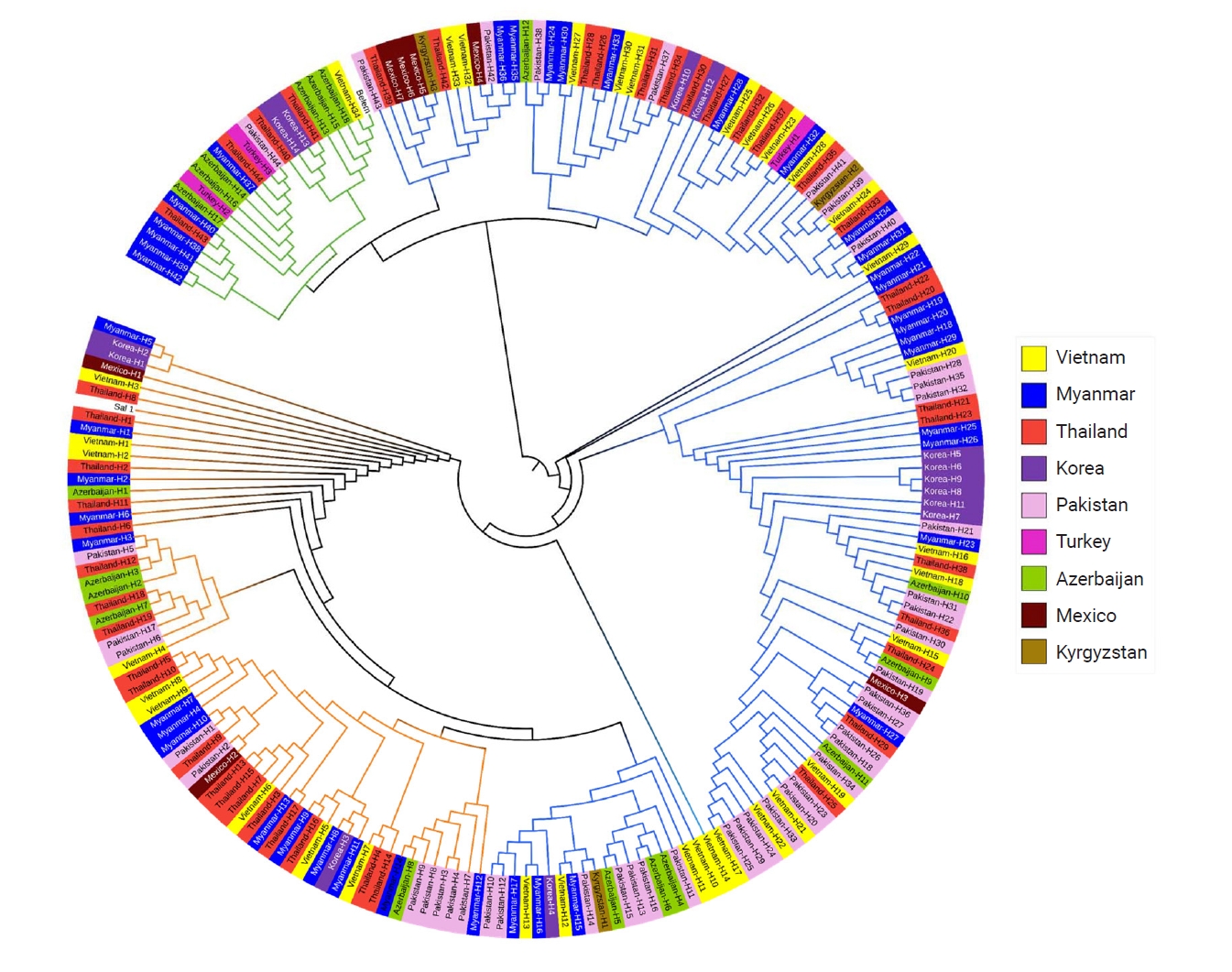

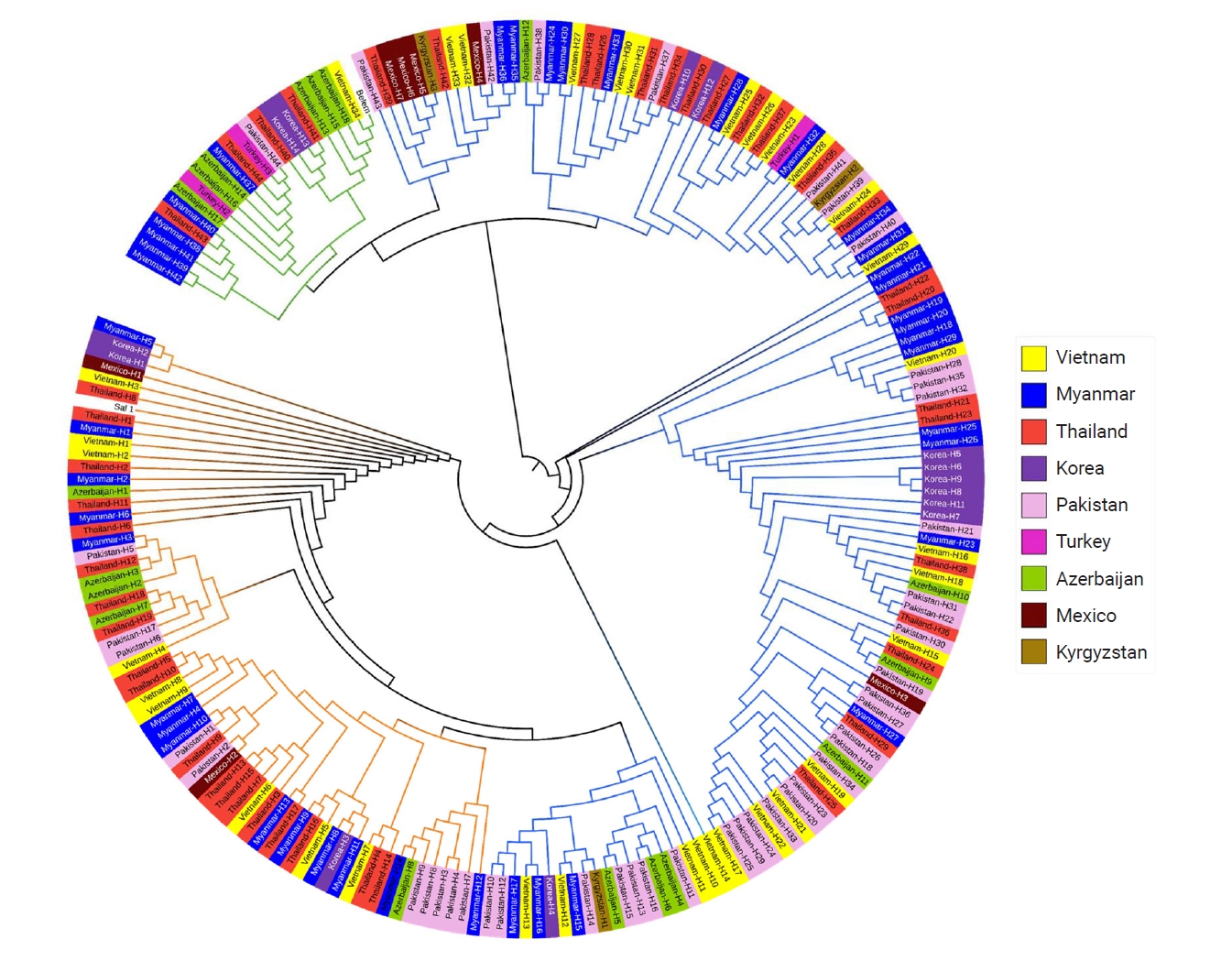

pvmsp-1 ICB 5–6 from Vietnam, Myanmar, Thailand, Pakistan, Turkey, Azerbaijan, and Mexico. Interestingly, 17 Qs was highly prevalent (92.9%) in Kyrgyzstan, while 21 Qs was predominant (81.5%) in Azerbaijan. Meanwhile, 10 and 14 Qs were predominant in Korea, and 15 Qs was prevalent (63.3%) in Turkey. For Thailand, 27 Qs was predominant (53.9%). The most significant polymorphic patterns of poly-Qs were detected in Myanmar. A phylogenetic tree was constructed to determine the genetic lineages of the global

pvmsp-1 ICB 5–6 (

Fig. 8). The phylogenetic tree branched into 3 major clusters, Sal I, recombinant, and Belem types, but no significant country-specific or region-specific clustering was identified. This pattern was further supported quantitatively by analysis of molecular variance, suggesting that 46.6% of the total genetic variance was attributed to differences among populations.

Discussion

This is the first report on genetic characteristics of

pvmsp-1 ICB 5–6 in Vietnamese

P. vivax isolates. Substantial genetic polymorphisms were identified in the Vietnam

pvmsp-1 ICB 5–6 population. All 3 allelic types, Sal I, recombinant, and Belem, were observed, but recombinant types were predominant. Similar patterns of predominance of recombinant allelic types were also identified in

pvmsp-1 ICB 5–6 populations from other countries, including neighboring Southeast Asian countries such as Myanmar and Thailand [

20,

27], except for

pvmsp-1 ICB 5–6 from Turkey and Azerbaijan, showing higher frequencies of Belem types. High prevalence of recombinant allelic types might be attributed to frequent recombination events between and among parasite populations with distinct genetic structures, which could be common in endemic areas where co-infection and/or super-infection allows active sexual recombination in the mosquito vector [

28]. Interestingly,

pvmsp-1 ICB 5–6 from the South-Central province of Khanh Hoa displayed a different allelic distribution from those from the Central Highland provinces of Dak Lak, Dak Nong, and Gia Lai. The reason for this difference remains unclear, and further investigation is necessary.

Amino acid changes and size polymorphisms of poly-Q repeats were the major factors causing the genetic diversity of Vietnam and global pvmsp-1 ICB 5–6 populations. The most significant amino acid changes were I792T and N873K, which were commonly identified in the global pvmsp-1 ICB 5–6 populations, suggesting they may be under balancing selections or possible functional constraints. Polymorphisms in poly-Q repeats were significant in recombinant and Belem types. Various numbers of poly-Qs ranging from 9 to 30 were identified in the global pvmsp-1 ICB 5–6 populations, and the patterns of poly-Qs differed by county. Generally, poly-Q heterogeneity was greater in Southeast Asian countries, including Myanmar, Thailand, and Vietnam, than in the other countries analyzed in this study. Interestingly, pvmsp-1 ICB 5–6 from the Central Highlands of Dak Lak, Dak Nong, and Gia Lai provinces revealed higher levels of amino acid polymorphisms and greater poly-Q heterogeneity than those from Khanh Hoa province, the South-Central region. The pvmsp-1 ICB 5–6 from Khanh Hoa exhibited limited genetic diversity, characterized by only an amino acid change and a predominant poly-Q lineage. This phenomenon could be due to the lower endemicity of malaria in Khanh Hoa than in the Central Highlands. High endemicity in the Central Highlands may maintain more diverse gene pools in the P. vivax population, enabling active recombination. While Khanh Hoa may harbor a less diverse parasite population, probably due to the low endemicity and restricted gene input, this drives the stable maintenance of genetic homogeneity. However, further comparative investigations for other polymorphic markers, such as circumsporozoite surface protein and apical membrane antigen-1, are necessary to understand the genetic differences of P. vivax populations between the 2 areas in Vietnam.

This study had several limitations. Only 4 malaria-endemic provinces in Vietnam were enrolled in this study, suggesting the results of this study could not provide the nationwide landscape of the genetic diversity in the Vietnam

pvmsp-1 ICB 5–6. Therefore, analysis of the gene from the other malaria-endemic provinces in Vietnam is necessary to understand and generalize the genetic nature of the gene in Vietnamese

P. vivax population. Considering that malaria transmission and the genetic structure of malaria parasites can be influenced by diverse factors, such as human migration and vector species [

29], further demographic analysis of the human population and distribution of mosquito vectors in the studied areas is necessary. Unequal numbers of global

pvmsp-1 ICB 5–6 sequences and limited numbers of countries due to the restricted availability of public genetic information about global

pvmsp-1 ICB 5–6 sequences are also limitations. The global

pvmsp-1 ICB 5–6 sequences that were gleaned from the previous studies also span a range of different chronological periods, suggesting that it is conceivable that the results of this study might not precisely depict the current genetic characteristics of the global

pvmsp-1 ICB 5–6 population. Interestingly, it was reported that Vietnamese

P. falciparum and

P. vivax populations exhibited different genetic structure and natural selection trends with other GMS countries, such as Myanmar and Thailand [

30-

34], emphasizing the necessity to investigate the

P. falciparum and

P. vivax populations in Lao PDR and Cambodia to unveil in-depth genetic lineages and evolutionary insights of the parasite population in the GMS.

In conclusion, this study demonstrated that Vietnam pvmsp-1 ICB 5–6 displayed substantial genetic diversity within the P. vivax population, produced by amino acid changes and poly-Q repeat length polymorphisms. Recombination was also one of the driving forces contributing to the genetic diversity of Vietnam pvmsp-1 ICB 5–6 by generating diverse recombinant types. Interestingly, different genetic profiles of Vietnam pvmsp-1 ICB 5–6 were detected between the Central Highlands and South-Central regions, suggesting possible genetic differentiation between P. vivax population in the 2 malaria endemic regions. These findings provide valuable insights into the evolutionary dynamics of Vietnamese P. vivax and highlight the importance of continuous molecular surveillance of the parasite for Vietnam’s malaria elimination goal.

Notes

-

Data availability

The data supporting the conclusions of this article are provided within the article. The original datasets analyzed in this study are available from the corresponding author upon request. All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article. The sequence data obtained in this study are openly available in GenBank of NCBI at https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/ under the accession No. PX388009–PX388147.

-

Author contributions

Conceptualization: Na BK. Data curation: Nguyễn TH, Nguyễn DTD, Lê HG, Võ TC, Na BK. Formal analysis: Nguyễn TH, Nguyễn DTD, Lê HG, Võ TC, Cho M, Na BK. Funding acquisition: Na BK. Investigation: Nguyễn TH, Nguyễn DTD, Na BK. Methodology: Nguyễn TH, Nguyễn DTD, Trinh NTM, Khanh CV, Quang HH. Project administration: Quang HH, Na BK. Resources: Trinh NTM, Khanh CV, Quang HH. Software: Nguyễn TH, Nguyễn DTD. Supervision: Khanh CV, Quang HH, Na BK. Writing – original draft: Nguyễn TH, Na BK. Writing – review & editing: Nguyễn DTD, Lê HG, Võ TC, Trinh NTM, Cho M, Khanh CV, Quang HH.

-

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

-

Funding

This work was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea grant funded by the Korean government (MSIT) (RS-2025-02413635).

-

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the staff in the Tropical Diseases Clinical and Treatment Research Department, Institute of Malariology, Parasitology, and Entomology Quy Nhon, Vietnam for their contribution and technical support in field work.

Fig. 1.Map of blood sample collection areas. Blood samples were collected from Plasmodium vivax-infected individuals in 4 provinces in Vietnam: Gia Lai, Dak Lak, Dak Nong, and Khanh Hoa.

Fig. 2.Genetic polymorphisms of pvmsp-1 ICB 5–6 in Vietnamese Plasmodium vivax isolates. Multiple sequence alignment of deduced amino acid sequences of 139 Vietnam pvmsp-1 ICB 5–6 sequences revealed 34 different haplotypes, classifying into Sal I, recombinant, and Belem allelic types. Sal I (XM_001614792) and Belem (AF435594) were used as reference sequences. Amino acids identical to Sal I are represented by dots. The dashes represent alignment gaps. The red arrows mark the predicted recombination sites.

Fig. 3.Allelic distributions of pvmsp-1 ICB 5–6 in the Vietnamese Plasmodium vivax population. Pie charts show the proportions of Sal I, recombinant, and Belem allelic types across the 4 provinces. Recombinant types were predominant in all provinces, while the Belem type was detected in only Dak Nong.

Fig. 4.Poly-Gln (Q) repeat variations in the Vietnam pvmsp-1 ICB 5–6 population. Diverse types of poly-Q repeats, caused by different numbers of Qs ranging from 15 to 26, were identified in Vietnam pvmsp-1 ICB 5–6. The frequencies of poly-Q patterns differed by province.

Fig. 5.Allelic distributions of pvmsp-1 ICB 5–6 in the global Plasmodium vivax population. Bar graph shows the proportions of Sal I, recombinant, and Belem allelic types in the global P. vivax population. Recombinant types were the most prevalent except for Turkey and Azerbaijan.

Fig. 6.Profiles of amino acid changes identified in the global pvmsp-1 ICB 5–6 population. The heatmap illustrates the frequencies of amino acid changes identified in the global pvmsp-1 ICB 5–6 populations compared to the Sal I reference sequence (XM_001614792).

Fig. 7.Poly-Gln (Q) repeat variations in the global pvmsp-1 ICB 5–6 population. Different patterns of poly-Q repeats were observed in the global pvmsp-1 ICB 5–6 populations. Great polymorphic patterns were identified, but no significant country- or region-specific pattern was detected.

Fig. 8.Phylogenetic analysis of the global pvmsp-1 ICB 5–6 population. A phylogenetic tree was constructed with the maximum likelihood method by the MEGA7 program, applying 209 global pvmsp-1 ICB 5–6 sequences and 2 reference sequences of Sal I (XM_001614792) and Belem (AF435594).

References

- 1. World Health Organization. World malaria report 2024. The Organization; 2024.

- 2. Võ TC, Lê HG, Kang JM, et al. Molecular surveillance of malaria in the Central Highlands, Vie tnam. Parasitol Int 2021;83:102374. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.parint.2021.102374

- 3. Duong MC, Pham OKN, Thai TT, et al. Magnitude and patterns of severe Plasmodium vivax monoinfection in Vietnam: a 4-year single-center retrospective study. Front Med (Lausanne) 2023;10:1128981. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmed.2023.1128981

- 4. Quang HH, Chavchich M, Trinh NTM, et al. Multidrug-resistant Plasmodium falciparum parasites in the Central Highlands of Vietnam jeopardize malaria control and elimination strategies. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2021;65:e01639-20. https://doi.org/10.1128/AAC.01639-20

- 5. Khanh CV, Lê HG, Võ TC, et al. Unprecedented large outbreak of Plasmodium malariae malaria in Vietnam: epidemiological and clinical perspectives. Emerg Microbes Infect 2025;14:2432359. https://doi.org/10.1080/22221751.2024.2432359

- 6. Lê HG, Võ TC, Kang JM, et al. Molecular profiles of antimalarial drug resistance in Plasmodium species from asymptomatic malaria carriers in Gia Lai province, Vietnam. Microorganisms 2025;13:2101. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13092101

- 7. Dayananda KK, Achur RN, Gowda DC. Epidemiology, drug resistance, and pathophysiology of Plasmodium vivax malaria. J Vector Borne Dis 2018;55:1-8. https://doi.org/10.4103/0972-9062.234620

- 8. Arnott A, Barry AE, Reeder JC. Understanding the population genetics of Plasmodium vivax is essential for malaria control and elimination. Malar J 2012;11:14. https://doi.org/10.1186/1475-2875-11-14

- 9. Holder AA, Blackman MJ, Burghaus PA, et al. A malaria merozoite surface protein (MSP-1) structure, processing and function. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz 1992;87 Suppl 3:37-42. https://doi.org/10.1590/s0074-02761992000700004

- 10. Beeson JG, Drew DR, Boyle MJ, et al. Merozoite surface proteins in red blood cell invasion, immunity and vaccines against malaria. FEMS Microbiol Rev 2016;40:343-72. https://doi.org/10.1093/femsre/fuw001

- 11. Valderrama-Aguirre A, Quintero G, Gómez A, et al. Antigenicity, immuogenicity, and protective efficacy of Plasmodium vivax MSP1 Pv200L: a potential malaria vaccine subunit. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2005;73:16-24. https://doi.org/10.4269/ajtmh.2005.73.16

- 12. Versiani FG, Almeida ME, Mariuba LA, Orlandi PP, Nogueira PA. N-terminal Plasmodium vivax merozoite surface protein-1, a potential subunit for malaria vivax vaccine. Clin Dev Immunol 2013;2013:965841. https://doi.org/10.1155/2013/965841

- 13. Herrera S, Corradin G, Arévalo-Herrera M. An update on the search for a Plasmodium vivax vaccine. Trends Parasitol 2007;23:122-8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pt.2007.01.008

- 14. Gibson HL, Tucker JE, Kaslow DC, et al. Structure and expression of the gene for Pv200, a major blood-stage surface antigen of Plasmodium vivax. Mol Biochem Parasitol 1992;50:325-33. https://doi.org/10.1016/0166-6851(92)90230-h

- 15. Portillo HAD, Longacre S, Khouri E, David PH. Primary structure of the merozoite surface antigen 1 of Plasmodium vivax reveals sequences conserved between different Plasmodium species. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1991;88:4030-4. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.88.9.4030

- 16. Putaporntip C, Jongwutiwes S, Sakihama N, et al. Mosaic organization and heterogeneity in frequency of allelic recombination of the Plasmodium vivax merozoite surface protein-1 locus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2002;99:16348-53. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.252348999

- 17. Ruan W, Zhang LL, Feng Y, et al. Genetic diversity of Plasmodium vivax revealed by the merozoite surface protein-1 icb5-6 fragment. Infect Dis Poverty 2017;6:92. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40249-017-0302-6

- 18. Cerritos R, González-Cerón L, Nettel JA, Wegier A. Genetic structure of Plasmodium vivax using the merozoite surface protein 1 icb5-6 fragment reveals new hybrid haplotypes in southern Mexico. Malar J 2014;13:35. https://doi.org/10.1186/1475-2875-13-35

- 19. Naw H, Kang JM, Moe M, et al. Temporal changes in the genetic diversity of Plasmodium vivax merozoite surface protein-1 in Myanmar. Pathogens 2021;10:916. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens10080916

- 20. Putaporntip C, Jongwutiwes S, Tanabe K, Thaithong S. Interallelic recombination in the merozoite surface protein 1 (MSP-1) gene of Plasmodium vivax from Thai isolates. Mol Biochem Parasitol 1997;84:49-56. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0166-6851(96)02786-7

- 21. Zeyrek FY, Tachibana SI, Yuksel F, et al. Limited polymorphism of the Plasmodium vivax merozoite surface protein 1 gene in isolates from Turkey. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2010;83:1230-7. https://doi.org/10.4269/ajtmh.2010.10-0353

- 22. Goo YK, Moon JH, Ji SY, et al. The unique distribution of the Plasmodium vivax merozoite surface protein 1 in parasite isolates with short and long latent periods from the Republic of Korea. Malar J 2015;14:299. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12936-015-0803-3

- 23. Moon SU, Lee HW, Kim JY, et al. High frequency of genetic diversity of Plasmodium vivax field isolates in Myanmar. Acta Trop 2009;109:30-6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actatropica.2008.09.006

- 24. Kang JM, Lee J, Cho PY, et al. Dynamic changes of Plasmodium vivax population structure in South Korea. Infect Genet Evol 2016;45:90-4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.meegid.2016.08.023

- 25. Kumar S, Stecher G, Tamura K. MEGA7: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 7.0 for bigger datasets. Mol Biol Evol 2016;33:1870-4. https://doi.org/10.1093/molbev/msw054

- 26. Excoffier L, Lischer HEL. Arlequin suite ver 3.5: a new series of programs to perform population genetics analyses under Linux and Windows. Mol Ecol Resour 2010;10:564-7. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1755-0998.2010.02847.x

- 27. Na BK, Lee HW, Moon SU, et al. Genetic variations of the dihydrofolate reductase gene of Plasmodium vivax in Mandalay division, Myanmar. Parasitol Res 2005;96:321-5. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00436-005-1364-0

- 28. Camponovo F, Buckee CO, Taylor AR. Measurably recombining malaria parasites. Trends Parasitol 2023;39:17-25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pt.2022.11.002

- 29. Rougeron V, Elguero E, Arnathau C, et al. Human Plasmodium vivax diversity, population structure and evolutionary origin. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2020;14:e0008072. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pntd.0008072

- 30. Kang JM, Lê HG, Võ TC, et al. Genetic polymorphism and natural selection of apical membrane antigen-1 in Plasmodium falciparum isolates from Vietnam. Genes (Basel) 2021;12:1903. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes12121903

- 31. Võ TC, Trinh NTM, Lê HG, et al. Genetic diversity of circumsporozoite surface protein of Plasmodium vivax from the Central Highlands, Vietnam. Pathogens 2022;11:1158. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens11101158

- 32. Võ TC, Lê HG, Kang JM, et al. Genetic polymorphism and natural selection of the erythrocyte binding antigen 175 region II in Plasmodium falciparum populations from Myanmar and Vietnam. Sci Rep 2023;13:20025. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-47275-6

- 33. Võ TC, Lê HG, Kang JM, et al. Genetic polymorphism of merozoite surface protein 1 and merozoite surface protein 2 in the Vietnam Plasmodium falciparum population. BMC Infect Dis 2024;24:1216. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-024-10116-6

- 34. Võ TC, Lê HG, Kang JM, et al. Genetic diversity and natural selection of circumsporozoite surface protein in Vietnam Plasmodium falciparum isolates. Malar J 2025;24:320. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12936-025-05585-2

, Đăng Thùy Dương Nguyễn1,2,†

, Đăng Thùy Dương Nguyễn1,2,† , Hương Giang Lê1,2

, Hương Giang Lê1,2 , Tuấn Cường Võ1,2

, Tuấn Cường Võ1,2 , Nguyen Thi Minh Trinh3

, Nguyen Thi Minh Trinh3 , Minkyoung Cho1,2

, Minkyoung Cho1,2 , Chau Van Khanh3

, Chau Van Khanh3 , Huynh Hong Quang3,*

, Huynh Hong Quang3,* , Byoung-Kuk Na1,2,*

, Byoung-Kuk Na1,2,*